Cardinal Charles Maug Bo believes the establishment of diplomatic relations between Myanmar and the Holy See on May 4 not only helps the Catholic Church’s relationship with this majority Buddhist country in Southeast Asia but could also “help build up Myanmar as a democracy and contribute to peace building in the country.”

In an exclusive interview with America during a visit to Rome, the cardinal-archbishop of Yangon, age 68, explained that his country of some 55 million people is “on the road to democracy” under the de facto leadership of the state counsellor and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and her government. But “it has still not reached that goal.”

After the establishment of diplomatic relations, Archbishop Paul Gallagher, the Vatican’s secretary for relations with states, told America, “The Holy See hopes that Myanmar will continue on the direction of democracy that it has taken in recent years.”

“The Holy See hopes that Myanmar will continue on the direction of democracy that it has taken in recent years.”

Cardinal Bo agrees. “That is our hope, too,” he said, “but how the church will promote the democracy is left also to us.” Right now, his main concern “is how we can help in building peace with the different ethnic groups, with the government, with the military, and how can we come up with a new constitution since there cannot be any amendment to the present one because of how the military framed it.” The constitution approved under military rule in 2008 reserves 25 percent of the seats in Parliament for the military.

Ms. Aung San Suu Kyi’s party, the National League for Democracy, won the national elections in November 2015, and after a peaceful transition to power, took the reins of government on March 31, 2016. “But the reality is that the military still holds the balance of power in the country,” the cardinal said, controlling not just Parliament but the Ministries of Defense and Home Affairs as well as the country’s borders. “The political situation is delicate.”

Nevertheless, Cardinal Bo said, “Since coming to power, Ms. Aung San Suu Kyi and her party have brought lots of improvement in the country, including in civil administration and taxation. Things are going well.

“There is freedom of speech in the press, and there are many free television channels, whereas in the past there was just the government and the military channels. Now people feel free to comment on the situation in the country. Over 70 percent of the population have smartphones.

“Constitutionally Aung San Suu Kyi’s administration still has no power over the military.”

“This is a major change,” the cardinal said.

There is freedom of movement for tourists and visitors, too. Under military rule “their movement was very restricted and every visitor would have been followed by the military intelligence,” Cardinal Bo said.

“We are very happy with all that,” the cardinal continued, “but the fact remains that constitutionally Aung San Suu Kyi’s administration still has no power over the military, especially in relation to the civil war with the Kachin and the plight of the Rohingya.”

A Little-Known War

Cardinal Bo, a member of the Salesian order, noted that while there has been much focus in the West on the plight of the Rohingya Muslims, “little publicity” has been given to the country’s civil war. It began in the 1940s, making it perhaps the longest-running conflict in the world. In February 1947 General Aung San Suu Kyi (the father of today’s state counsellor) sought to promote a federalist system but was assassinated the following July while working toward this goal. Burma, as the country was called then, gained its independence from Britain in 1948.

Little publicity has been given to the country’s civil war—perhaps the longest-running conflict in the world

There was “a certain amount of democracy in the country” between 1948 and the end of 1960, the cardinal said, but “Prime Minister U Nu aggravated the situation in 1961 by declaring Buddhism the state religion,” provoking strong resistance from the ethnic minorities in the north, northeast and west of the country.

The military, which took power in 1962 and ruled until 2011, “blocked this move to federalism,” Cardinal Bo said. “They centralized power and the control of the natural resources.” The civil war with the Kachin—most of whom are Christian—continued to be fought over minority rights and control of the state’s resources.

Kachin, Myanmar’s northernmost state on the border with China, has a population of 1.7 million people. It is rich in natural resources, and most of the country’s jade comes from this area. The Kachin people “want to make sure there is federalism and justice for all in the country before going for a ceasefire and peace,” Cardinal Bo said.

While both sides claim to want a ceasefire, some Kachin leaders do not want it yet; the armed groups allow them to control the extraction of jade and other mineral wealth resources. Some native-born Baptist pastors also want the war to carry on for the same reason. The reality is that the generals control much of the precious stone resources and have sold a lot of the jade to China, he said.

“Aung San Suu Kyi wants a federal system. She wants to stop the war; she wants peace.”

“Aung San Suu Kyi wants a federal system. She wants to stop the war; she wants peace. She is working for that and held a conference in September 2016 and again last May 24 to move toward that goal.” She asked all the different armed ethnic groups to attend the May peace conference, and the military was present, too. “She definitely has great influence on these ethnic groups. They trust her, but they don’t trust the military,” the cardinal stated.

He identified the “second big problem” as “the plight of the Rohingya.” The Rohingya are Muslims, he said, and about one million of them live in Rakhine State, which has a total population of 3.2 million, the majority of whom are ethnic Rakhine and Buddhists. The Rohingya have a long history of migration that stretches back 200-300 years when they began moving from Bangladesh to Myanmar. “They’ve been moving back and forth, so neither the Myanmar government nor the Bangladesh government has given them citizenship. So, in a sense they’re stateless people,” Cardinal Bo explained. But the relationship between Myanmar and Bangladesh “is not too close, not too friendly,” he said. “Both sides are reluctant to really talk about this issue of the Rohingya. But it’s a problem that involves two states.”

When the military junta ruled, it exploited such ethnic tensions all over the country. It repressed the Rohingya in 1978 and in the 1990s and drove many into Bangladesh. Following the outbreak of more violence between Buddhists and Rohingya Muslims in 2012, more than 120,000 of the Rohingya were displaced. Many now live in refugee camps near the border with Bangladesh. Since last October, some 90 persons were killed and 34,000 were displaced. They live in “a very poor place, that has no facilities,” said Cardinal Bo.

Some months ago, the cardinal visited a settlement for the Rohingya in Sittwe, the capital of Rakhine state, an area controlled by the army. Here the Rohingya people’s freedom of movement “is very restricted. The police take them to the market by truck and bring them back again,” he said.

Ms. Aung San Suu Kyi has come under much international criticism for the treatment of the Rohingya.

Ms. Aung San Suu Kyi has come under much international criticism for the treatment of the Rohingya. But, he said, “I agree with her: There is no genocide here; ethnic cleansing is not happening.” Nevertheless, he believes her government made a mistake when it refused to let an international team investigate the human rights situation in Sittwe.

Citizenship for the Rohingya is a controversial proposal in Myanmar. According to the cardinal, Ms. Aung San Suu Kyi “would say that we have to go case by case, rather than give it to them all.”

He believes “the solution should come together with Bangladesh and a nearby country, Thailand, that could support us in resolving their situation.” China has offered to mediate the crisis, but the N.D.L. government was suspicious of China’s intentions and rejected the offer. The cardinal said there is opposition from many in the Buddhist community to the idea of Rohingya citizenship. Even the use of the term Rohingya is a source of national tension. It is the name Rakhine Muslims use to describe themselves, apparently derived from Rohang, a Muslim term for what is now Arakan state in western Myanmar. Rakhine Buddhists object that the term confers historical legitimacy on the Muslim community. “At the same time, there are Buddhist monks that are very understanding,” Cardinal Bo said, “and, although they cannot offer any solutions, they advocate the protection of all people of whatever race or religion.”

The Church in Myanmar

Some years back, Myanmar’s religious affairs minister even asked him “to inform the Holy See not to use the word Rohingya because it is very sensitive in the country,” the cardinal said. “It is an explosive term, and the government does not want to use it so as not to create any problems or riot in the country.”

“That would give the military an excuse to return and seize power,” he explained. “The military is just waiting in case of any emergency. According to the constitution, they could come back and take control in the country in a situation of confusion or emergency at the national level.”

“The military is just waiting in case of any emergency.”

The Catholic Church in Myanmar is trying to help address the civil war and the plight of the Rohingya, Cardinal Bo said. The bishops’ conference organized a two-day religious peace conference, from April 26 to 27, attended by 200 people from all religions, including Buddhist monks, Muslim and Hindu religious leaders, many ambassadors and various international non-governmental organizations. “We focused on how the religious leaders could exercise their influence for peacebuilding,” he said. The conference established working groups for nation building in five areas: education, peacebuilding, religious harmony, special care for children and women and development.

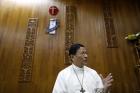

Pope Francis made Archbishop Bo a cardinal in November 2014, and this has made a difference to his ministry in the country, he said. “It’s important in front of the government, and in front of the Buddhist community, and in front of the Muslims and the Hindus. They acknowledge my personal role in the country and especially for the uniting the different religious people.”

He revealed that “practically every month, we have meetings on peacebuilding, which include the Buddhist monks, the Hindus, Muslims and the other Christians. We work together.”

“Practically every month, we have meetings on peacebuilding, which include the Buddhist monks, the Hindus, Muslims and the other Christians.”

But the fact that the military still holds the balance of power “is a big obstacle to what Aung San Suu Kyi wants to achieve,” he said. Her lawyer and advisor U Ko Ni, a Muslim, was assassinated at Yangon airport on Jan. 31. He was a top constitutional lawyer, a powerful voice in the N.L.D., an advocate for the rights of minorities, including the Rohingya, and had studied the present military constitution and created the role of state counsellor for Ms. Aung San Suu Kyi.

The military has said he was assassinated because of a sort of antagonism or hatred for Muslims, but the cardinal said most people do not believe this. “The reality is that he was a threat to the military because he was going for a new constitution,” Cardinal Bo said.

He believes Ms. Aung San Suu Kyi herself could be in danger “because she is the only one with the leadership skills and experience to keep the country on the road to democracy. If she were no more, there would be upheaval in the country.”

Cardinal Bo emphasized that “the dialogue with the military is critical.”

Given this reality, Cardinal Bo emphasized that “the dialogue with the military is critical.” Despite the delicate situation, he is confident that Ms. Aung Suu Kyi “knows how to move and what space she has.”

Cardinal Bo described Myanmar’s church—with its 16 dioceses, 700,000 faithful, 350 priests and 2,500 women religious—as one “of the poor and for the poor.” Government and society view it as a “prestigious” national institution, “while the Burmese community and Buddhist monks recall that there has never been any conflict between them and the Catholics or Christians in this land.”

When I interviewed him in 2009, Cardinal Bo confided that he had two dreams for his country: The first was the passing of the constitution and the peaceful transition to democratic rule; the second was that the pope would visit Myanmar.

The first has already happened, but the second has not—yet. Ms. Aung Sang Suu Kyi met Pope Francis at the Vatican in May, and though they got on well, she did not invite him to visit Myanmar. The cardinal believes “she would like to invite him, but she is a little careful because of the sensitivity of the Buddhist community, and so wants to wait a while longer before doing so.”

Cardinal Bo has already invited the pope: “We Catholics want him to come. But we understand her situation, and we don’t want to push her on this. For us, he is really the person of Jesus Christ. While Pope Francis is especially loved by us, the Buddhists and the other Christian denominations also have a very high regard for him. They see him as a moral leader in today’s world. For our part, we hope and pray he will come one day soon.”

The cardinal used to speak quite eloquently about the misery of the stateless Rohingya but now he also makes excuses for Aung San Suu Kyi's policies of inaction and denial. While he is trying to be a bridge-builder with the powers that be, he needs to make sure he does not become an apologist for persecution.

If Cardinal Bo wishes to say there is no genocide, he should at least be clearly opposed to the policies that exclude Rohingya from employment, education, travel within Burma, intermarriage and voting rights. Rohingya used to have all these rights. Returning them on a case by case basis, as he suggests, has proved to be a bureaucratic nightmare since the military confiscated people's identity information, and because the government is not operating in good faith.

It might be useful if the Cardinal would continue to build public support for full pluralism in Myanmar, with visible and widely televised activities that bring all ethnicities together. It is am international right for people to name themselves, and there should be no hesitation about naming the Rohingya. To refuse to even say their name is to become complicit in their social erasure.