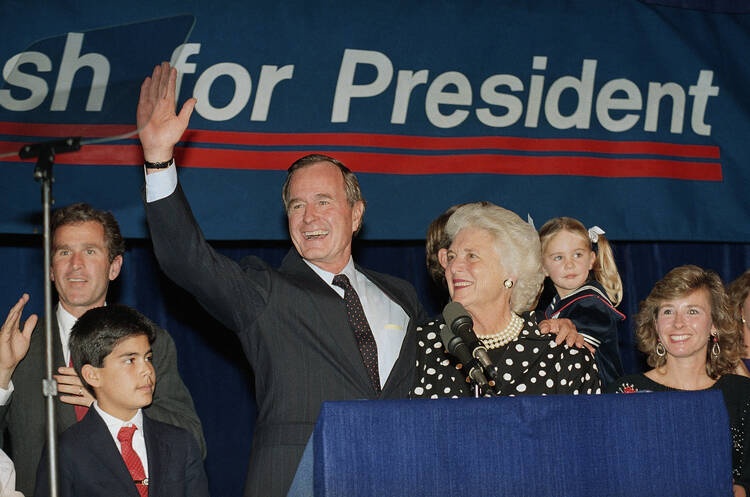

‘George Bush’s Message to Michael,” I recall, was the headline that blared across two whole pages of The Boston Herald on Aug. 19, 1988. The Herald had chosen to print in its entirety the speech that Vice President George Bush had delivered the night before in New Orleans, accepting the Republican nomination for president. In Massachusetts in 1988, no one was in doubt about who Michael was: the Bay State’s own Gov. Michael Dukakis, the Democratic nominee.

Mr. Bush’s speech, expertly crafted by the veteran speechwriters Peggy Noonan and Craig Smith, is best remembered for “Read my lips: no new taxes,” a promise President Bush would later break in order to balance the federal budget. But first-runner up for best-remembered phrase lies in his remarks on the importance of civil society: “This is America,” he said. “The Knights of Columbus, the Grange, Hadassah, the Disabled American Veterans, the Order of Ahepa, the Business and Professional Women of America, the union hall, the Bible study group, LULAC, ‘Holy Name’—a brilliant diversity spread like stars, like a thousand points of light in a broad and peaceful sky.”

That phrase, “a thousand points of light,” was much satirized and derided by critics. But unfairly so. Mr. Bush was onto something: While government has a role to play in the pursuit of the common good, our charitable and voluntary associations are similarly indispensable, and those who have a religious worldview have historically led the way. In this, Vice President Bush was aligned with the thinking of John Courtney Murray, S.J., who viewed civil society as an ascending world of social organizations that, along with government, form a coherent, cohesive whole.

But in the contemporary United States, it would be more accurate to say that such an arrangement was America. As William T. Cavanaugh has observed, Father Murray’s vision of civil society has been inverted. “The rise of the state,” says Cavanaugh, “is the history of the atrophying of such [intermediate] associations.” In an important sense, American political history is not a tale of the triumph of individual autonomy over the authoritarian state; it is rather a tale of the triumph of the state over the individual, through the progressive absorption of the intermediate associations of civil society. Cavanaugh’s evidence includes “the exponential and continuous growth of the state” in the postwar period, “in the progressive enervation of intermediate associations,” as documented by Robert Bella, Robert Putnam and others; and “the symbiosis of the state and the corporation that signals the collapse of the separation between politics and economics.”

Yet politicians on both sides of the aisle have started to acknowledge the importance of those intermediate associations and are attempting to reverse the trend. Mr. Bush’s son, George W., during his tenure as president, created the first White House Office of Faith-Based and Community Initiatives. President Obama has a similarly styled initiative, and in this issue of America, the first to feature a cover story by a sitting secretary of state, John Kerry writes about the new Office of Religion and Global Affairs, a testament to Mr. Kerry’s belief in the power of religion to effect meaningful, positive change, sometimes in partnership with government agencies but more often on its own.

Perhaps we can say that a revival of sorts is in the works, or a least a growing recognition of the importance of the third sector and its religious actors in providing for the common good. Perhaps we are a step closer to retrieving what Mr. Bush called in his acceptance speech “a better America…an endless enduring dream and a thousand points of light.”