Shortly after 9 P.M. on an August summer evening in 1974, practically all televisions in the United States were tuned in to the three major networks so that people could bear witness to a historically startling announcement. Seated behind a desk and before the cameras and their hot klieg lights (which never failed to make him perspire and required him to have a handkerchief at the ready to dabble his upper lip), the man with a sheaf of papers read from a prepared text. After some minutes, he came to the penultimate section of his address. He said:

…I have never been a quitter. To leave office before my term is completed is abhorrent to every instinct in my body. But as President, I must put the interest of America first. America needs a full-time President and a full-time Congress, particularly at this time with problems we face at home and abroad.

To continue to fight through the months ahead for my personal vindication would almost totally absorb the time and attention of both the President and the Congress in a period when our entire focus should be on the great issues of peace abroad and prosperity without inflation at home.

Therefore, I shall resign the Presidency effective at noon tomorrow. Vice President Ford will be sworn in as President at that hour in this office…

With that, Richard Milhous Nixon, the 37th President of the United States, resigned the office that had been the goal—and the summit—of his political life. With those few words, he effectively ended his political life, a life which was never without drama and always intermingled with controversy. The next morning, after giving a rambling and nearly maudlin remarks in the East Room, where staff, aides, government officials, and the few remaining stalwarts gathered to hear him reminisce about his parents, quote Theodore Roosevelt about “being in the arena” and muse about the vicissitudes of life, he strode out of the White House with his devoted wife Pat by his side. Together, they walked the red carpet out to the awaiting Marine One helicopter, where atop the top step, he looked out at the assembled crowd and swinging his two arms out wide, gave a final “V” for victory salute that he often gave—and was known for—in an imitation of the two famous personages of his political life, Winston Churchill and Dwight D. Eisenhower (the man Richard Nixon had loyally served as Vice President for eight years). Once done, he turned around and entered the helicopter, which flew him to Andrews Air Force Base to an awaiting Air Force One which, in turn, would fly him back to California to an unwelcome retirement and an uncertain future. He would leave behind a nation he had once led nearly buckling from a constitutional crisis (resulting from the Watergate affair) which resulted from his actions and his behavior. When he entered the presidential plane for that cross-country flight, it wouldn’t be known as Air Force One anymore, once the very moment his resignation came into effect while airborne. It simply became another government aircraft, finally signaling that the pomp and the trappings of office which he so delighted in (one of the very few things in life that offered him any pleasure) were no longer his to possess, enjoy—or control.

Richard Nixon was a complicated man who happened to be a conflicted man.

Having been a poor man, who struggled to make his way in life, he associated with rich men.

Obviously intelligent and knowledgeable about history and the workings of government, he ended up using those gifts awkwardly and not always for good ends.

He wanted to be seen as an enlightened statesman, sure of his diplomatic skills and abilities, yet he gave way to his worst impulses as a political hack and hatchet man by making up “enemies lists” and spying on his actual and/or perceived opponents.

He wanted so much to be remembered as a president who brought about peace throughout the globe, yet kept escalating war by whatever means, whether at home or abroad.

He wanted to be someone who unified people who had been rent apart by years of assassinations and social and political upheaval, yet became the very personification of that division.

Obviously intelligent and knowledgeable about history and the workings of government, he ended up using those gifts awkwardly and not always for good ends.

In his presidential campaigns, he presented himself as a paragon of decency and correct language, yet, thanks to a misguided and ill-begotten use of a tape-recording system (which he originally intended to utilize as a tool and a resource for the history of his presidential administration), was revealed to be a person of unbecoming biases and “expletive-deleted” speech.

He told CBS’ 60 Minutes’ Mike Wallace (whom he admired and wanted to be his White House Press Secretary once he was elected—and which Wallace turned down) that to be a leader, a public official ought to be “respected” rather than loved; when in truth, candidate and President Nixon wanted sorely to be both, though he could never admit it. He went throughout his life not wanting to be ridiculed or dismissed by others, a goal that consumed him and eventually embittered him.

He assumed an air of toughness in order to hide his inner insecurities though he had to have an inner reserve of steel to endure what he had to in order to achieve what he believed to be his life’s goals. He wanted to adhere to his Quaker mother’s Hannah’s admonitions on doing good, yet he easily succumbed—and took a liking to—to the rough-and-tumble of politics.

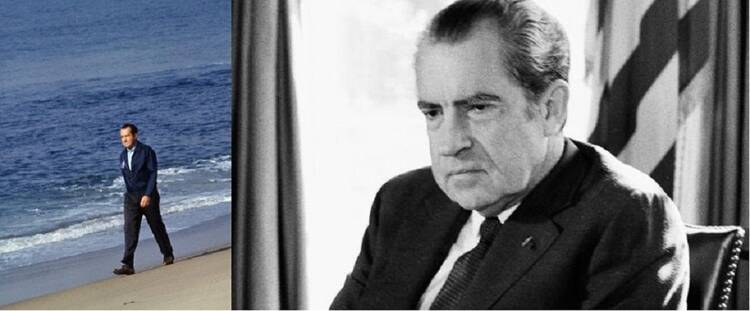

He wanted so much to be like—and appear to be like —the common man, when the attempts he often made often backfired on him; the most famous example being the time when (in an not-so-unconscious attempt to ape the Kennedy style and aura), he was seen clad in a windbreaker (complete with the presidential seal) to walk on a windswept beach, walking not barefooted, but in his wingtips. And his eating habits also evoked wonder: his everyday lunch was a scoop of cottage cheese with a slice of Bermuda onion, lathered with ketchup or Worcestershire sauce (something his successor, Gerald R. Ford, an “everyman” if there ever was one, did the same for his daily luncheon). Even on a summer’s day, he would go into one of the rooms of the White House and ramp up the air conditioning, only to issue an order that the fireplace be lit at the same time while he sat in an easy chair, with the ever ubiquitous yellow pad in his lap, awaiting for him to write a statesman’s eternal words with a felt-tip pen. Small talk was torture for him; he’d rather discourse on the intricacies of foreign affairs and maybe gossip about other foreign leaders and their doings. He played the piano the way he played golf: with great effort and sometimes awkwardly. And his attempts to handle a yo-yo at the Grand Ole Opry met with mixed results. He would read books but not newspapers; he relied on daily “digests,” clippings with stories and editorials that buttressed his worldview and shrank it at the same time, increasing his isolation from others and the outside world.

Though he averred any interest in domestic affairs—he actually did what he could to dismantle however he could, the programs of his two immediate predecessors, the New Frontier and the Great Society—when it came right down to it, he did sign into law legislation that improved the quality of life for many people, laws which made better our air, our water, our health and our education. Perhaps, unconsciously, he remembered his beginnings in Whittier, California, where his family struggled to make a living in various enterprises like a lemon ranch or a combination gas station/grocery store or having the worry of having a brother who suffered from tuberculosis (and eventually died from it) or working to earn good grades so he could get ahead academically and professionally. Perhaps those struggles embittered him; though in his public life he might have outwardly dismissed them and sought to leave them behind while creating a new public persona (the various “New Nixons” that propped up over the years) for himself. Just the same, he didn’t reject outright those proposals that came across his desk—with a few strokes of the presidential pen, he brought into existence laws that helped enhance people’s lives.

And when he ran for re-election (one in which nearly everyone, layman and political expert alike, said he would win handily—and did) he could not rest on the knowledge that it was assured and that he finally had one political campaign he didn’t have to “sweat” out, literally or figuratively. He had to exert the powers of his office in order to show that he was at the top of the political pyramid and that he intended to stay there, only to tumble down to an ignominious end barely two years later, in disgrace and despair, leading him to a post-presidential life of writing books, giving speeches, and acting as an “elder statesman” to those who came after him, eventually dying of a stroke in 1994 at the age of 81, just days after the wife of his erstwhile presidential rival did (Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, who died at the age of 64 from non-Hodgkins lymphoma).

The most notable event of his post-presidential years was the series of controversial interviews with David Frost in 1977 when he admitted—perhaps in a moment of emotional clarity—that he gave those who opposed him a sword, noting that “they twisted it with relish.”

No one can know what the quest for power and for glory can do to a person who is ordinarily possessed of the possibilities for good; we can only be bemused when we see the effects—and the toll—it takes on such a person and wonder why. We may know—or think we know—everything there is to know about a person who seeks high office and wants to direct the affairs of history. But when it comes to a complex personality like Richard Nixon, we may never know—and what is even more intriguing to think about, he himself may not have known, either, if he really understood who he was, what he did, or why he did it.

What can be said for certain is what Winston Churchill said in another time and in another context. What he said about Soviet Russia can be applied to the person of Richard Nixon, who resigned 41 years ago: our 37th President was a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma. And the lesson of Richard Nixon may be this: a president should never have any of these attributes, lest the country go through another constitutional trauma like the one we went through, ever again.