Homily for the Fourteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time

Readings: Isaiah 66:10-14c Galatians 6:14-18 Luke 10:1-12, 17-20

Prayer is a mystery. Perhaps because, whatever else it may be, prayer is communion with the living God who is, above all else, a mystery.

Sadly, one great mystery of prayer is the impoverished devotional life of so many Christians. They recite memorized prayers, or they fling a sentence or two of their own toward heaven—but only when they find themselves in need. They do not realize how starved they are of God! Why are they content with so little when such nourishment could be theirs?

Using the city of Jerusalem as a synecdoche for God himself, the prophet Isaiah exclaimed:

Oh, that you may suck fully

of the milk of her comfort,

that you may nurse with delight

at her abundant breasts! (66:11).

Are Christians spiritually starving because they have never been taught to pray? Or are they simply reluctant to develop the discipline demanded by so many of life’s most enriching experiences?

It cannot be a question of teaching alone because many a great saint learned to pray without lessons. St. Thérèse of Lisieux was still a schoolgirl when this conversation, recorded in her autobiography Story of a Soul, took place:

At this time in my life nobody had ever taught me how to make mental prayer, and yet I had a great desire to make it. Marie, finding me pious enough, allowed me to make only my vocal prayers. One day, one of my teachers at the Abbey asked me what I did on my free afternoons when I was alone. I told her I went behind my bed in an empty space which was there, and that it was easy to close myself in with my bed-curtain and that “I thought.”

“But what do you think about?” she asked.

“I think about God, about life, about ETERNITY…I think!” The good religious laughed heartily at me, and later on she loved reminding me of the time when I thought, asking me if I was still thinking. I understand now that I was making mental prayer without knowing it, and that God was already instructing me in secret.

A few helpful notes on this little passage. First, Marie was one of her older sisters, who took charge of little Thérèse after the early death of their mother. Second, those capitalizations, ellipses, and italicizations are found in the saint’s handwritten manuscript. Words alone could not capture Thérèse’s intensity. Finally, what Thérèse called “mental prayer” would now be known as either meditation or contemplation.

When I entered priesthood formation in high school, an older cousin, who had spent a few weeks at a convent, gave me a book entitled “Mental Prayer.” I began to read it, but I did not go far. That word “mental” conjured up images of Brainiac, an erstwhile foe of Superman. So, Thérèse and I were both to stumble into a life of prayer without the aid of a good, written guide, though she herself became this for me when I later read her while still in high school.

What is meditation, and how do you begin to do it? St. Francis de Sales wrote a wonderful little book called Introduction to the Devout Life. He taught that meditation is bringing thoughts to mind in order to move your heart and will toward God.

What sort of thoughts? Anything that might move your heart and will toward God. Remember how Thérèse put it, “I think about God, about life, about ETERNITY…I think!”

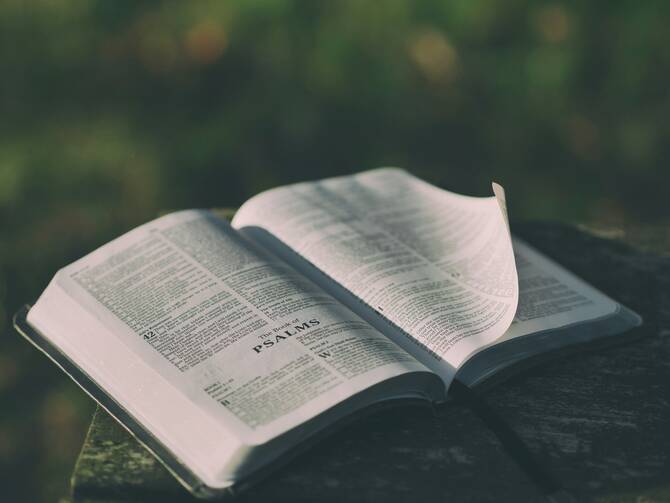

In meditation, pride of place goes to sacred Scripture. You read it slowly. The goal is not to read a lot. It is only to find a verse, or even a phrase, that touches you emotionally, that makes you desire God. And when the snippet no longer entices, you move on.

But Christian meditation is not limited to Scripture. You can also:

- Ponder a crucifix or some other sacred image.

- Read the life of a saint.

- Gaze upon the beauty of nature.

- Tackle a poem.

- From a distance, think about what is happening in your life.

- Listen to Simon and Garfunkel’s Greatest Hits, the soundtracks of “Jesus Christ Superstar” and “Godspell,” or songs by John Denver, Neil Diamond, Carole King and Bread. If you are not a child of the ’70s, my sympathies. Make your own adjustments.

Francis de Sales said that we bring thoughts before our mind. We do this by listening, looking or reading. Then we wait for God to move our hearts and wills toward him. Thérèse crawled into the secluded space behind her bed and thought—as she put it—about God, life and eternity.

And what is contemplation, the companion and successor to meditation? You stop thinking and simply stare at God, if you will. You are content just to be in the presence of this one whom you cannot see, cannot hear and cannot prove. Yet you know this same someone is with you, delighting in your company.

I can give you contemplation in an image. My father received hospice care in our home. I was on my way to Mass the last time I saw him alive. He had asked to sit up in bed because lying on his back was too painful. My mother was sitting on the side of the bed with him. They were holding hands; neither was speaking.

There was nothing more to say to each other. They both knew that the only thing that mattered now was being there with, and for, the other. That’s contemplation, just gazing upon your beloved. It is hard to do initially—in both human and divine relationships! It often does not last long, but a good draft of it is long-lasting. Like meditation, it will keep you from dying of thirst when you could be sucking fully from the milk of God’s comfort.