The prolific and often eccentric Swiss theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar (1905-88) must surely be considered one of the most influential Catholic thinkers of the past century. The author of over 100 books, founder of a secular institute and a publishing house, and a tireless translator, Balthasar left a legacy that professional theologians are still grappling with nearly four decades after his death.

For many, Balthasar’s name conjures up associations with a conservative theological agenda. He was, to be sure, decidedly traditional on certain hot-button issues (like women’s ordination), and his influence on the thinking of both St. John Paul II and Pope Benedict XVI is well known: John Paul II, for instance, named him a cardinal (although Balthasar died mere days before the consistory at which he would have been formally installed), and Benedict XVI collaborated with him on numerous academic projects (for example, founding the journal Communio together with Henri de Lubac, S.J., in 1972). And yet, to think of Balthasar exclusively in these terms would be to overlook many of the most innovative and farsighted aspects of his theological project.

Balthasar, for his part, rejected the “nonsensical division of humanity into a ‘left’ and a ‘right’” and deliberately sought ways of encouraging greater “cooperation and heartfelt like-mindedness” within the church, especially during the most turbulent years of the 20th century. For instance, his celebrated 1952 book Razing the Bastions anticipated key ideas that would predominate 10 years later at the Second Vatican Council, such as the need for a more active role for the laity and a greater theological emphasis on the interrelation of the church and the world.

Even more fundamentally, his entire cast of mind tended toward creative ressourcementof perennial Christian truths. It was fruitless, he wrote in Razing the Bastions, to “cling tightly to [existing] structures of thought....A truth that is merely handed on, without being thought anew from its very foundations, has lost its vital power” and eventually “becomes dusty, rusts, [and] crumbles away.” Nor did he deny that this obligation extended to the very structures of the church, which must continually renew its mission in the context of the contemporary world and amidst the contingencies of history.

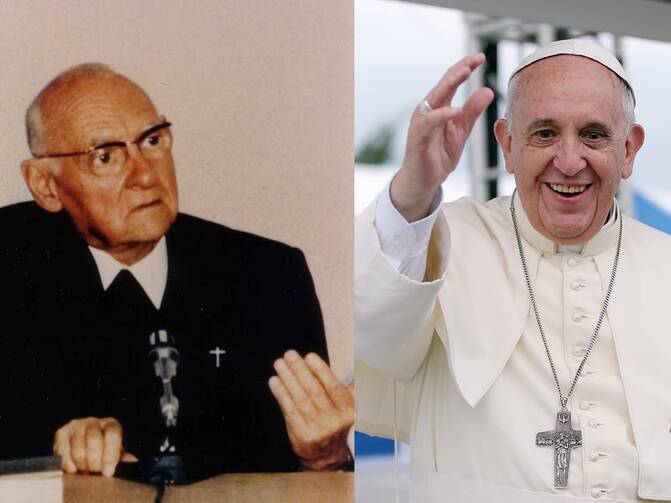

It was this side of Balthasar that most likely attracted the interest of a young Jorge Mario Bergoglio, who was known to have read, cited and assigned Balthasar’s work during his years as a Jesuit rector, professor and novice master in Buenos Aires. The Jesuit Diego Flores, who knew Bergoglio since the mid-1970s, went as far as to call Balthasar “one of Francis’ favorite authors,” and scholars likeJacques Servais andMassimo Borghesi have carefully traced the Swiss theologian’s influence on the future pope. In fact, many aspects of Francis’ remarkable program of ecclesial renewal are prefigured in Balthasar’s vision for the church.

Anti-Roman attitudes

To see this more clearly, one need look no further than a still-timely book published by Balthasar in 1974 entitled Antirömische Affekt (Anti-Roman Attitude). In English, the book was published with the considerably more anodyne title The Office of Peter and the Structure of the Church. Here one finds Balthasar’s most sustained attempt to articulate a theology of the papacy, and by extension an implicit account of legitimate ecclesial authority. Written during the contentious papacy of Paul VI—the controversial encyclical “Humanae Vitae,” which many credited with a sharp decline in church attendance,had been published only six years earlier—the book takes as its starting point a number of polemical criticisms of the institutional church that were in circulation at the time.

Prominent theologians like Hans Küng had complained publicly about the magisterium’s paternalistic style. Another theologian Balthasar responded to in the text, Regina Bohne, had called for an “anarchical” church, one “free from any [form of organized] authority.” Balthasar detected echoes of a much-older “anti-Roman attitude” that ran from the young Newman to Luther and all the way back to the early Christian community at Corinth. Indeed, Balthasar writes, “[t]he anti-Roman attitude is as old as the Roman Empire.” Rather than dismissing these criticisms out of hand, however, Balthasar acknowledges the need to “take seriously and appraise realistically the misgivings about the Church’s leadership,” since there is always a danger that the “power of [ecclesial] leadership once again becomes sharply separated from spiritual renewal.”

For Balthasar, the problem with contemporary criticisms lay not with their objections to any particular papal teaching or policy, but in their rejection of papal authority as such. Power, Balthasar insisted, was integral to the structure of the church, having been established by Christ when he commissioned the Twelve. Peter in particular is the “permanent exponent” of the apostolic order, having received in its entirety “that which [Christ] intended to the Twelve collegially” (cf. Mt. 16:18-19).

To be sure, the “power” in question was not based on the exceptional merit of those on whom it was bestowed (as Peter’s own repeated failures amply demonstrate), nor was it one meant for domination: The Greek term exousia, used in the Gospels to mean “power” or “authority,” has specific connotations of healing and service to the community. But such power was specifically allocated, a point to which Balthasar ascribes significant theological meaning. It is thus a “romantic” and “abstract” concept of Christianity that envisions the church as a homogenous and “amorphous brotherhood,” rather than a differentiated unity in which the “interdependence of all” is made manifest in the variety of diverse ecclesial offices.

Archetypes of authority and ministry

It is here that we come to the most enduring feature of Anti-Roman Attitude, which is the idea of a “Christological constellation,” or a “constitutive group” surrounding and drawn together by Jesus, apart from which he cannot be properly understood. Just as “[o]ne sole human being would be a contradiction in terms,” so too would the God-man Jesus Christ be unrecognizable detached from the personal relationships that gave structure to his life and mission.

Balthasar imagines the “constellation” broadly—Joseph, Mary Magdalene and even Judas all have their place—but he emphasizes five central figures in particular: Mary the Mother of God, John the Baptist, Peter, John the Beloved Disciple and Paul. All these figures help illuminate the mystery of Christ by sharing in his saving work; and so they become, by extension, “archetypes” of various missions in the church: Peter the shepherd, the Virgin Mary the exemplar of lay holiness, John the embodiment of intimate personal love of Christ, the Baptist a prophetic voice in the wilderness, Paul the prototypical missionary and so on.

Even within the constellation, the Virgin Mary does not relate to Jesus in exactly the same way as Peter, and John’s position is different from Paul’s. This should alert us to the need to attend to the specifics of office in a given case. Although Peter’s role as shepherd requires that he strive to preserve and promote an authentic unity founded in the shared love of Christ, this does not mean he can “carry out his office in isolation,” nor can he act out “monarchically” against others in the constellation.

The ecclesiastical power structure is not, writes Balthasar, like a “pyramid” (in any case, only Jesus would stand atop it) but rather a “multidimensional reality,” a “network of tensions” that play off one another and balance one another in distinct and overlapping ways. For example, Peter’s authority is false if it is not leavened by a Johannine love of Christ; the Marian “yes” to God predates the calling of Peter and conveys the true identity of the church more perfectly than his role as shepherd; the Baptist’s prophetic orientation to the future reminds Peter of the need to bear witness to the One who will come again. In other words, Balthasar says, “Peter…must be continually learning…he too must take his bearings by the all-encompassing totality of the Church, which expresses itself concretely in the dynamic interplay of her major missions.”

A vision of papal authority

We have here the outlines of a program of ecclesial renewal that was as important in Balthasar’s time as it is our own. Peter’s power is integral, but it is not absolute. His authority is circumscribed by the tensions inherent in the structure of the church—tensions which are a necessary aspect of any true communion. Demands for a one-size-fits-all solution to a given question confronting the church therefore risk undermining Peter’s primary task of being a visible sign of unity (incidentally, according to Balthasar, this was Paul VI’s mistake in “Humanae Vitae,” when he held up as a universal teaching an ideal which could have only ever applied to a “small…devoted company” and so incurred the indignation of the flock at large).

Vatican II, with its emphasis on collegiality and its fundamental teachings on the church as the whole people of God, indicated a path toward greater ecclesial communion. This communion, however, would need to be complemented by the “spiritual deepening of authority itself,” especially in the figure of the pope. Ultimately, the papacy is animated not by a centralizing principle but by what Balthasar calls an “eccentric” one, which consists in stepping out from the “center” to stand in solidarity with the sinners, the forgotten and the lost, whom God calls God’s own. In order to do this credibly, Peter must be present to the global church in its full diversity and humanity, not as a punitive police power but as the personification of pastoral closeness. One might call him a bridge-builder.

The resonances with Francis’ papacy can now be seen coming more clearly into view. Given what we know to be Balthasar’s influence on him, and the seriousness with which Bergoglio thought about the papacy years before ascending to the throne of St. Peter, it is entirely reasonable to think that Francis took this vision of reformed papal power to heart.

For example, during his “exile years” in Córdoba, Francis reportedly read all 40 volumes of Ludwig von Pastor’s magisterial History of the Popes, which provides exhaustive evidence of the many ways in which the successors of Peter have historically forgotten their proper role. More to the point, Francis, like any other Catholic, would have been able to look at the previous half-century of papal history leading up to his election and see signs of Peter’s increasing isolation—whether due to disciplinary zeal, doctrinal retrenchment or exalted personal styles.

It might not be too much to view Francis’ turn to synodality, his personal simplicity of spirit, his general refusal to wield doctrine as a “control mechanism,” and his visible orientation of the papacy toward the Johannine charism of love as a program for re-embedding Peter within the constellation.

The church is not reducible to a single personality or power, of course; but this does not then mean that personal power as such is alien to it. Instead, the deepest kind of reform would consist in showing how both authority and power can justify their place in the order of love, and so point toward the One who has established that order for the sake of our redemption and freedom. As we continue to discern the fruits of Francis’ pontificate, we might be surprised to find in Hans Urs von Balthasar a helpful guide to understanding the past 12 years.