A Reflection for Friday of the Fifteenth Week in Ordinary Time

Find today’s readings here.

If you’re living today and keep hearing that we are in “ordinary time,” you might ascribe our modern meaning to it. “Yep, all this is pretty ordinary, nothing to see here.” One of the paradoxes of being religiously observant is the problem of familiarity, the more we see or do something, the more automatic it becomes, until it is, well… ordinary.

But what if I told you that’s not what “ordinary time” means? That it is actually a call back to the Church’s old Latin roots and refers to numbers (ordinals) and to order (ordo). This is the time of the liturgical year when the weeks are numbered, as opposed to other seasons like Lent. This numerically ordered (but not ordinary) time is meant to pull us into the richness of the biblical witness, so that in three years we’ve read pretty deeply into our tradition.

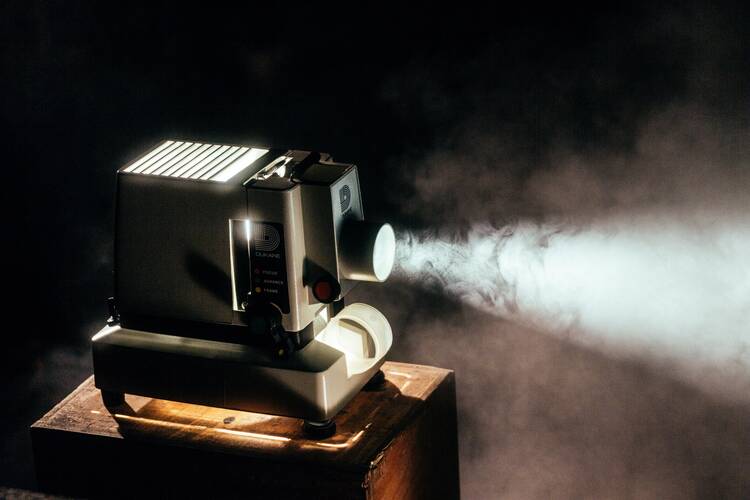

For our purposes, I propose we rename this day “This makes my head hurt Friday.” Far from ordinary, this collection of readings stacked up next to each other is mind-blowing. I love the artform of film, so let’s try noticing the strangeness of these texts by imagining them as scenes.

Scene 1: A very ancient time presented as a vivid memory. On this fateful day, the God of Israel shows God’s might over everything, and most importantly over the imperial powers that have enslaved God’s people. God does this by destroying humans and animals, except those who have marked their homes with blood to show that they belong to God. The people of God are commanded to keep these observances always and to remember this horrifying day and their own survival. This is an extraordinarily frightening and memorable scene, full of violence and death. (Ex:11:10–12:14)

Scene 2: Many years have passed, and a song is performed by a liturgical leader with the gathered community—descendants of those who did not die that day. Their singing is a way to remind themselves that their ancestors were spared because they belonged to God, and so must they belong to God. The song expresses gratitude and also reiterates that they continue all of the observances and sacrifices that marked them as a faithful people. (Ps 116:12-13 and 16bc, 17-18)

On this very-far-from-ordinary day we are asked to reflect on how complex religious traditions are and how they exist in time and are passed along through people embedded in cultures.

Scene 3: Many more years have passed, and we are in the film’s historical present: the first century of the common era. We see a small group of people tired and dusty from hours of walking. They gather some grain from a field to feed themselves and are swiftly accused of breaking the law. The authorities are looking for a fight and this breach in religious observances provides a way to attack them. Their young leader Jesus (the real target) responds to the accusations by pointing out that in their tradition observances were sometimes discarded out of need, like hunger and service. He then calls into question everything they think they know, by reminding them that God has said this through the prophets, not once, but many times: “I desire mercy, not sacrifice.” His accusers should hear Hosea saying God desires closeness not “burnt offerings”; Samuel asking for listening hearts not “sacrifice”; Amos declaring God wants no “solemnities or offerings,” but for “justice [to] surge like waters, and righteousness like an unfailing stream”; and Ecclesiastes warning against “fools offering of sacrifice” while they continue to do evil.

However, it is Micah who is most movingly in the background of Jesus’ pushback against the religious authorities. After the prophet counts off extravagant offerings of “thousands of rams, with myriad streams of oil” he seems to allude to the Passover slaughter asking if the sacrifice of a firstborn is required? He then answers with one of the most eloquent passages of Scripture:

“You have been told, O mortal, what is good,

and what the Lord requires of you:

Only to do justice and to love goodness,

and to walk humbly with your God.” (Micah 6:8).

On this very-far-from-ordinary day we are asked to reflect on how complex religious traditions are and how they exist in time and are passed along through people embedded in cultures. The killing of the firstborns is barbaric; it recalls a time of unbridled brutality and a people who survived. The stories we tell need context, and we often lose the meaning because we no longer know the context. God kept telling God’s people to stop it with all the observances and to just devote themselves to justice and goodness. Maybe the end of our film is just a black background with white lettering that says, “… and Jesus was right.”