The Roman historian Tacitus, writing near the time of Jesus, described how the Pax Romana was experienced by people, like the Celts and Jews, who had been conquered by the Romans: “They make a desolation and call it ‘peace,’” he wrote, quoting Calgacus, a besieged Caledonian chieftain.

As Christians, this is not the sort of peace we seek.Jesus of Nazareth made it clear that he was not in favor of a desolate peace, a negative peace—peace based on the sword, military threats and power. Jesus lived in a war zone under foreign military occupation in a period of civil war and violent insurgency against the foreign occupiers and the domestic leaders who cooperated with the occupying forces. He and his family were refugees, according to the definition of the 1951 Convention on Refugees; they fled genocide, as described in the 1948 Convention for the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. Yet he lived his life practicing and preaching peace-building, people-building, relationship-building and reconciliation.

For the church, a tradition of just peace has been hiding in plain sight. It is not a new development, although it has become more recognized and embraced in recent decades. It was given to us by Jesus. Jesus dialogued with enemies and with poor and marginalized persons, raising them up and healing impoverished, war-traumatized peoples, driving out their demons. Jesus not only had a declaratory policy urging peace-building, he lived peace-building and commissioned us to follow him.

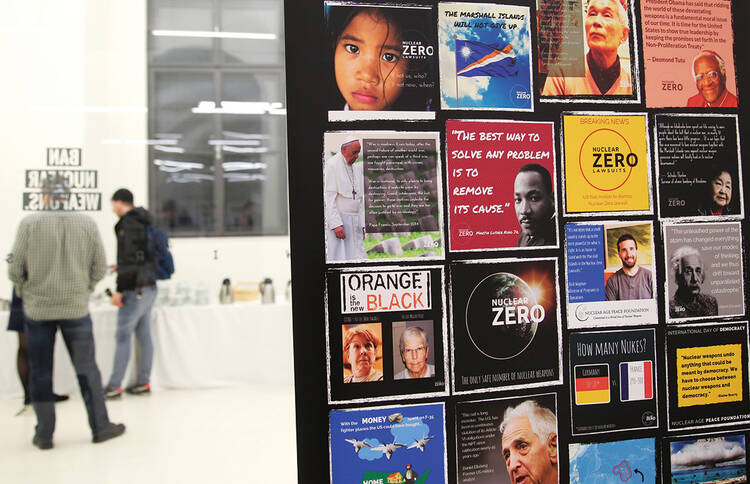

Just peace in the area of nuclear weapons means moving away from a peace based on desolation and mutually assured destruction, and instead moving to a peace based on right relationships and mutually assured reductions of nuclear weapons. Pope Francis recently revised the Holy See’s position on nuclear deterrence, strengthening the church’s historic commitment to nuclear disarmament. The church underscores the desolation that would be caused by any nuclear detonation, accidental or intentional, through the Holy See’s engagement in the international meetings on the humanitarian impact of nuclear weapons.

The Way the War Ends

Our task today is to find ways to build a better, more resilient peace. What kind of peace do we seek? Just peace criteria include participatory process, right relationships, restoration, reconciliation and sustainability. Wars end, but they do not always end with the positive peace of right relationships we are called to build as Christians. Sometimes wars end in that desolation we call peace. More than a quarter of a century after the fall of the Berlin Wall, we should remember that the Cold War ended in a cold peace that persists today, contributing to the problems we now face with nuclear weapons.

The Cold War ended with a settlement of the Second World War and the status of what had been a divided Germany. There was diplomatic engagement between the United States and Russia on a host of issues, from economic accords to cooperation in space, including the historic Nunn-Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction program that removed and safeguarded thousands of nuclear weapons and materials.

But there was no reconciliation between the United States and Russia or between Russia and the newly independent states of Europe. There was no “truth and reconciliation commission” for the Cold War, no public apologies for crimes or acknowledgement of harms done during decades of conflict, no systems to reintegrate former foes through symbolic politics that built a wider and deeper public support for peace with Russia.

After more than 45 years of movies, stories and politicians vilifying the Russians, there were no “Sesame Street” characters or action movie franchises building public support for the idea of “the Good Russian, Our Friend.” The Cold War did not end in World War III and foreign occupying forces, thank God. But because it did not end with a military battle, too many of our Cold War nuclear weapons and alert force postures and cultures of suspicion remained in place.

In just peace terms, a standard tool of peace-builders is Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration/Reconciliation, called D.D.R.—that is, the building of “right relationships.” For the United States and Russia, there was no D.D.R. process. We had some disarmament, without demobilization and without enough building of deeper relationships. To achieve deeper disarmament we need to build deeper relationships. To build deeper relationships, we need more people-building relationships. That means not just state government activities but exchanges between church and civil society, dialogue and engagement to broaden the work of reintegration and reconciliation.

Some practical work lies ahead. The church and most state parties to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty recommend deeper cuts to nuclear arsenals. On disarmament, U.S. and Russian interests coincide in preventing proliferation and reducing the costs of maintaining nuclear weapons by having much smaller arsenals.

Greater demobilization is also needed. The United States, Russia and other countries must better safeguard and secure their remaining nuclear weapons by removing them from a hair-trigger alert status. The past strategy of maintaining a dispersed and mobile nuclear arsenal, aimed at nuclear deterrence, should cease.

But further disarmament and demobilization will elude us until we address the “R” in D.D.R., building stronger right relationships. Disarmament can strengthen relationships of trust through regular inspections and information sharing that promotes transparency and accountability regarding nuclear weapons and materials. New and continued cooperative activities in counterproliferation and nuclear safety, reaffirming existing commitments, adhering to current nuclear agreements and sharing information on the costs of nuclear arsenals and potential cost savings can also help build better relationships.

The United States and Russia have a track record of cooperation on nuclear issues, from the Megatons to Megawatts program, which converted highly enriched uranium to usable energy, to the Global Initiative to Combat Nuclear Terrorism. The United States has abided by the terms of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty for decades, protecting public health and saving money. Ratifying the test ban treaty would deepen the commitment not to use nuclear weapons and help build trust.

Other Paths to Peace

There are other ways to build relationships beyond bilateral approaches, particularly at a time when bilateral relations are strained. Non-state venues and multilateral processes should be pursued. The nuclear security summits, the Proliferation Security Initiative, partnerships to prevent proliferation and the Global Threat Reduction Initiative (which removed highly enriched uranium and plutonium from 18 countries, more than enough for 100 bombs) are important models.

Relationships are also deepened by working together, multilaterally and with nongovernmental organizations, in responding to foreign disasters and emergencies. Whether responding to tsunamis or terrorist attacks, multilateral response and cooperation builds trust and capacity. That may prove helpful if radiological dispersal devices (so-called dirty bombs) or nuclear weapons actually are detonated, whether by accident or by terrorists.

Unfortunately, this is a real concern. Islamic State militants stole over 80 pounds of non-weapons grade uranium from Mosul University in Iraq in June 2014, and weapons experts report that the Islamic State has used chlorine gas attacks in Iraq. While the group has the ability to make and use weapons of mass disruption more than weapons of mass destruction, its capacity to disperse fear and destabilize politics is considerable. We cannot wait until bilateral relations improve to further the nuclear safety and security, disarmament, N.P.T. and non-nuclear use agendas.

Increasing the outreach and participation of states that gave up their nuclear weapons programs, like South Africa and Argentina, would ground multilateral conversations in the connection between nuclear reduction and freeing greater resources for economic development. Increasing multilateral capacity-sharing, cooperation and coordination, including cooperation of militaries, N.G.O.’s and religious actors, should be pursued also in humanitarian assistance, disaster relief and public health. Building those muscles of multilateral cooperation are important ways to build relationships and track records of cooperation that may help thaw frozen relations that can have spillover effects in the nuclear arena.

In international relations we talk about boomerang politics and forum shopping—when politics is blocked in one venue, you pursue alternate forums. Widening the net of relationship-building and the issues that we use to encourage cooperation can keep momentum moving while bilateral disarmament talks are stalled.

Pope Francis points a way forward. In “The Joy of the Gospel” he lays out his peace plan. In sum, he urges dialogue, dialogue, dialogue—within society, among states, with other faiths, with reason and science—to build a people of peace through reconciliation. Peace-building is people-building, Pope Francis tells us, and every person is called to be a peacemaker. Inequality and exclusion breed violence, so development is a path to peace.

What can the church bring to that dialogue? Religious actors bring three “I’s” to world politics: institutions, ideas and imagination. The church has rich institutions to foster dialogue, reconciliation and right relationships through its justice and peace commissions, Catholic universities and N.G.O.’s, the pontifical academies and the Holy See’s diplomatic corps. When action is stalled at the governmental level, the church can continue dialogue using this vast array of global institutions.

Resurrection Politics

Perhaps more important is what the church brings in ideas and imagination. There have been many times in recent history that the church has been told an issue was dead on arrival, that there was no political will or capacity to address it. But religious actors, in partnership with civil society and interested states, have instead successfully practiced resurrection politics, raising up issues as diverse as debt relief (the “Jubilee campaign”) and assistance to countries ravaged by H.I.V./AIDS, human trafficking and land mines in ways that helped the poor. They can do it again in the arena of nuclear weapons and global economic development.

Why? In an information age, ideas matter, and old, pre-state actors like the church have powerful ideas that have contemporary application. We know that norms are most entrenched when no one talks about them, when they are so accepted that they are unnoticed. When norms are debated and discussed, the normative train has already left the station. The old norm is under siege and new space is being opened for new ideas to be considered.During the Cold War, particularly in its early years, policymakers debated using nuclear weapons. The “taken for granted” ideas became the need to retain nuclear weapons for nuclear deterrence.

Now policymakers do not debate using nuclear weapons. That norm of non-use has gained strength and must be continued. U.S. leaders as dissimilar as President Reagan and President Obama have further declared a desire to rid the world of nuclear weapons. This is a discussion religious actors must help sustain. We cannot keep silent or fall prey to cynicism and despair, masked as “realism,” which are profoundly at odds with our Christian DNA of hope.

When the U.S. Catholic bishops in 1983 published “The Challenge of Peace,” urging nuclear disarmament, it was criticized as idealistic, utopian and naïve. But in a few short years, many of the bishops’ recommendations came to pass. Today the church must remain part of the nuclear dialogue, contributing a religious imagination that allows us to envision a world that includes our enemies.

The question “What kind of peace do we seek?” presupposes agency, that we can seek a positive peace based on right relationships with the world’s poor, future generations and past enemies. We must not “make a desolation and call it peace.” The power of religious actors to bring positive change is often underestimated in a world of sovereign states, but we must not underestimate ourselves.