God indeed appears in diverse places, sometimes hidden. Two examples stand out for me, one in Manhattan, the other in the South Bronx. Both concern poverty and prayer. The first is Pennsylvania Station. Whenever I am nearby, I walk through its vast passageways to experience the painful sense of disconnectedness they evoke. Strangers cluster together with little awareness of one another. The main concourse is crowded, especially at holiday times, with travelers who stare up at the huge electronic sign reporting arrivals and departures. Some might be praying, but only they would know.

A plexiglassed area, with a section of seating for those with more expensive tickets and another for those with less expensive ones, is off limits to others; and many travelers sit outside this area on the floor or lean against the walls.

But in cold weather, Penn Station also serves as a huge shelter for homeless people. Their tattered plastic bags contrast sharply with the sleek luggage of ticketed travelers. Sometimes asleep on the floor, homeless men are generally left to themselves in severe weather. At such a sight, the hidden God becomes present to me as I recall Paul’s words, “God chose what is low and despised in the world to shame the strong” (1 Cor 1:28).

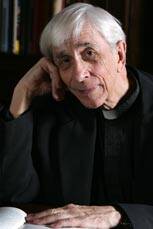

The other place for finding God in a more direct and positive way is Abraham House in the South Bronx. There God is front and center. No disconnectedness, but a community in which prayer and service act as the keys to seeing the face of Jesus precisely in the “low and despised of the world.” No matter how cold the weather, inner as well as physical warmth characterizes what occurs on wintry days among the primarily Mexican families who gather for weekend Masses as well as for various forms of assistance—material and spiritual. A group of Little Sisters of the Gospel and an elderly priest are the catalyst. Most have ministered at Rikers Island, the huge jail and prison facility in the East River. Given their firsthand awareness of the link between incarceration, race and poverty, it is all the more understandable that Abraham House should have a live-in program for prisoners, who also are among the low and despised to whom God is close. A number of the local people who attend Mass or who seek food, moreover, have relatives who are in prison, so they know what prison is like, if only from the long waits and frustrations of visiting loved ones behind bars. The prisoners, assigned by the courts as a rehabilitative measure, help on weekends with all the activities, while during the week they go to their jobs or continue a search for them or else attend substance abuse programs.

Mass there is the Mass of “the least” among the poor, many of whom are affected by our harsh immigration laws. As I arrived one Sunday morning, a sister told me that the Mass would have as a special intention an elderly woman who had died three days before in Mexico. None of her adult children here, however, could attend the funeral because of their undocumented status. They brought fresh flowers as a way of expressing their love for the one who had died. In New York, the sons survive on off-the-books jobs, which pay little and in the bad economy are increasingly hard to find.

These two scenes—Penn Station and Abraham House—are reminders that seen or unseen, God is present everywhere and reminders, too, of God’s special love for the world’s disenfranchised. One of the sisters said on a recent visit that it is precisely in those they serve, “the least,” that they find their own strength. Bolstered by an hour’s prayer each day before the Blessed Sacrament in their tiny chapel, they are sustained by this awareness day by day and by their faith.

What a beautiful testament to the hidden places of God. Thank you!