(This review of Thomas Merton’s The Seven Storey Mountain ran in the October 16, 1948 issue of America)

Twentieth-century Augustine

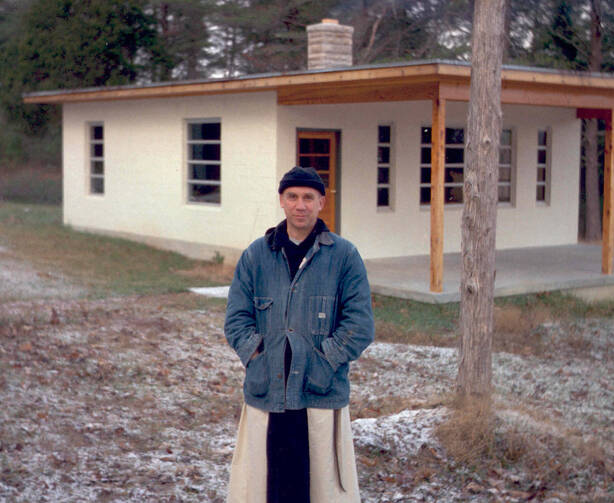

Thomas Merton, after living in ten years what most men live in 30, entered the Trappist Monastery at Gethsemani, Kentucky, when he was 26 years old. This former modern of moderns--bored, ego-centered, sensual--has been a monk for seven years, getting closer and closer to God.

Raised by a Quaker mother and a sort of Anglican father, (both of whom died when he was very young) the author, after an erratic education in France and England, wound up, of all places, at Columbia University, fully convinced that the joys of sex and alcohol and fame were the major concerns of living.

The Seven Storey Mountain is undoubtedly one of the most significant accounts of conversion from the modern temper to God that our time has seen.

Autobiographies of converts are becoming more and more frequent, but I know of none that reveal the abysmal vulgarity of our secular world as this does—and that, at the same time, makes real for the reader, Catholic and non-Catholic, the truths of the Church. God's grace is almost tangible for Merton and he manages to make it so for the reader.

It is undoubtedly one of the most significant accounts of conversion from the modern temper to God that our time has seen. Msgr. Fulton J. Sheen calls it a "twentieth-century form of the Confessions of St. Augustine."

Clare Boothe Luce says men will turn to it a hundred years from now "to find out what went on in the hearts of men in this cruel century." This is no ordinary autobiography. "Who touches this book touches a man."

Parenthetically, it is remarkable that two of Merton's friends and fellow students, one of them a Jew, were baptized. The aware young men of his generation are apparently discovering earlier than their predecessors the futility of living without the faith. A powerful force is the grace which converts men on Broadway and 116th Street, probably the most secular campus in the world, where the atmosphere is charged with the heavy dullness of John Dewey's naturalism, where young Marxists gather to protest this or that, where a step away is St. Paul's Chapel, usually empty of students and always empty of the Sacrament.

When a man writes like Frater M. Louis, as Merton is now named, the reviewer wants just to quote, and there are scores of quotable passages. The book is, in one aspect, a crushing arraignment of our modern civilization.

There was no room for any God in that empty temple full of dust and rubbish [his own soul], which I was now so jealously to guard against all intruders, in order to devote it to the worship of my own stupid will.

And so I became the complete twentieth-century man…I became a true citizen of my own disgusting century: the century of poison gas and atomic bombs. A man living on the doorsill of the Apocalypse, a man with veins full of poison, living in death.

And when he had worked with Catherine de Hueck in Harlem:

The brothels of Harlem, and all its prostitution, and its dope-rings, and all the rest are the mirror of the polite divorces and the manifold cultured adulteries of Park Avenue: they are God's commentary on the whole of our society…Harlem is, in a sense, what God thinks of Hollywood.

Perhaps the sentence which the worldly-wise intellectuals of 1948 ought most to ponder is a simple statement that comes near the end of his story when Merton had entered the monastery; this time, to stay.

Thomas Merton: "I became a true citizen of my own disgusting century: the century of poison gas and atomic bombs. A man living on the doorsill of the Apocalypse, a man with veins full of poison, living in death."

"So Brother Matthew locked the gate behind me and I was enclosed in the four walls; of my new freedom."

Young Thomas Merton craved fame as a writer. Now Brother M. Louis worries lest his writing, ordered by his Abbot, may not stand in the way of the true humility he seeks to achieve.

This reviewer is as chary as any of overestimating a book's worth. Mediocre stuff that no one would read more than once has too often been hailed as a masterpiece. It is hard to believe, however, that The Seven Storey Mountain is not destined to endure—certain sections in it, anyhow. Whether it does or not, it is a profoundly moving, spiritual document. It ought to be read. Catholics should read it and then buy copies for hesitating, prospective converts. It is worthy of a place very near The Confessions on the shelf and in a man's heart.

Merton left the world and then rejoined the world, rather more than one

might expect from a Trappist Monk and then left this life and this world.

I like the Seven Storey Mountain and wish that I too might have become

a Trappist, God willing.

I recommend Monica Furlong’s biography. To think that the review was written in 1948! Prescient and great to read. I still admire Thomas Merton, would love to have met him.