Take these broken wings and learn to fly

All your life

You were only waiting for this moment to arise.

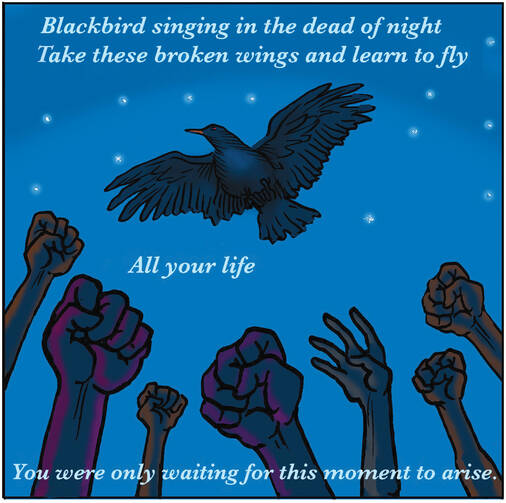

The Beatles’ song “Blackbird” is either a civil rights anthem or a response to transcendental meditation in India, depending on whose story you believe. Paul McCartney claims to have written it in honor of the 1960s movement for black equality; other members of the band have their own recollection of the song’s origins. Perhaps both explanations are true.

I found myself reconsidering the song earlier this year when Jon Batiste performed his own moving rendition of “Blackbird,”just voice and piano, on “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert.” I was not familiar with Batiste before he was brought on as the new “Late Show” band leader, but I quickly learned that this Juilliard-trained jazz pianist from a musical New Orleans family is a burgeoning force on the New York music scene. Still, my first impressions were lukewarm; the show seems to highlight his frenetic and jovial personality more than his actual musicianship.

So when I finally heard his performance of “Blackbird,” I posted the video on my Facebook page with the caption, “Finally the talent is revealed.” A friend commented that it was the first time he had “felt like ‘Blackbird’ was the gentlest, most spiritually-based black power song in the world.” Of course, that got me thinking. Certainly the idea of “Blackbird” being about being black had crossed my mind. But what was it actually saying to me today?

Take these sunken eyes and learn to see

All your life

You were only waiting for this moment to be free.

Whether McCartney was actually invoking an image of black struggle when he wrote “Blackbird” in 1968 is less important to us interpreters and listeners who are dark. The Catholic theologian David Tracy defines “the classic” as a text or other human creation with an “excess of meaning” that “demands constant interpretation and bears a certain kind of timelessness—namely the timelessness of a classic expression radically rooted in its own historical time, yet calling [out the interpreter’s] own historicity.” Today, it would be nearly impossible for African-Americans not to interpret the “excess of meaning” in this Beatles classic through our contemporary experience of struggle and liberation.

The subject is a blackbird singing, flying and seeing light in the dark, black night. Her wings may be broken, but the poet bids her, learn to fly. Her eyes may be sunken and tired, but the poet bids her, learn to see. Arise and be free: there is light in the dark, black night.

McCartney’s song is not the only art to use a blackbird to evoke freedom. In the early 1970s, Father Clarence Joseph Rivers, the pioneering African-American liturgist, commissioned his designer and collaborator David Camele to create an image of the Holy Spirit. Instead of a white dove, the Spirit of God is depicted as a blackbird. The image became a hallmark of not only Rivers’s work but also the ongoing inculturation of African-American culture into Catholic worship and theology. Rivers and Camele even used the image in a series of red, black and green pectoral crosses for the country’s black Catholic bishops.

So when I listen to “Blackbird” in 2016, given the most recent campaigns advocating on behalf of the dignity of black human bodies, it is not surprising that I, or any one of us, hear this classic with fresh perspective. When Alicia Keyes covers the song she makes the connection more explicit, singing some of the lyrics in the first person: “I was always waiting for this moment to be free.”

Being black in the United States poses a risk of a very particular form of socially conditioned despair. Certainly everyone’s experience is different; and yet most black people are at least somehow aware of this gnawing, nagging existential problem. In our country’s social mythos, blackness has for so long been connected with deep-seated racial fear, sexual menace and predatory violence. It is not just white Americans whose unexamined racism reflects this attitude. To be black in the United States means having to wrestle with this toxic legacy. Across the country a new generation of young African-Americans and their allies are joining a long line of activists who have fought to reclaim black identity. But as important as community organizing and political protests are, nothing can transform one’s self-image, indeed the whole trajectory of one’s life, like poetry, music and religion.

This year during Holy Week I found myself praying the Liturgy of the Hours with “Blackbird” still on my mind. The texts of night prayer reached down and grabbed me in the gut:

The night shall be no more. They will need no light from the lamps or the sun, for the Lord God shall give them light, and they shall reign forever (Rev 22:4b-5).

Night holds no terror for me sleeping under God’s wings (Good Friday Antiphon).

Through Christ, our very relationship to night is transformed. Perhaps the night is not eradicated, but instead the light of Christ illuminates its beautiful and glorious opacity. I cannot sufficiently communicate the depth of my experience here in prose. The words of the Beatles’ song are far more effective: blackbird fly, blackbird fly. Not only do black lives matter, black bodies soar on wings once broken, and see with eyes once sunken. Even in the midst of a bleak social crisis, we can sing our way into freedom.

Not only is “Blackbird” a classic; in the hands and voice of a gifted black artist, it can be prophetic. Music is a symbolic language of sound and poetry. And symbols, unlike mere flat signs, can participate in the reality to which they point; the best art reaches toward sacramentality, communicating God’s grace. And if, as I believe, the human body is a privileged sacramental bearer of God’s word and grace, the very act of a black artist singing into the dark, black night can move the listener toward a deeper experience of the truth.

That Facebook friend, who happened to be white, told me Jon Batiste’s rendition of “Blackbird” brought him to tears. Concern for the flourishing of black life is not and should not be the exclusive purview of black folks. The particularity of this moment in our country, along with my friend’s patient trust in the slow work of God in his own heart, disposed him to receiving God’s grace. God will reveal God’s self in the stuff of life, using human experience, and in this case human artistry, to gift us with revelation. This is the sacred potential of art, too: its ability to move our minds and hearts toward the living God, to use symbol and metaphor—always imbedded in the murky particularity of human experience—to move us toward the transcendent.

Blackbird fly,

Blackbird fly, into the light of the dark black night.