The scriptures summon us. “Be holy, for I, the Lord, your God, am holy” (Lv 19:2). The duty is direct and demanding, but where do we begin? What hope do we have of meeting such a goal? Ironically, our first glimpse of God’s holiness is the sight of our own brokenness. When grace begins to shine in our lives, sin shows, and we understand our need for a savior. So, oddly enough, our awareness of sin is a reason for our hope. You can’t reform what you do not recognize; you cannot repair what you fail even to realize. That’s the teaching, and here’s a tale to illustrate it.

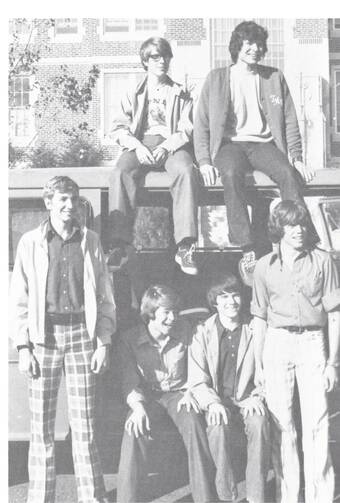

My senior year of high school, I was one of six young men to accept the invitation of Father Charles, our teacher, to visit Capuchin Franciscan houses of formation on the East Coast. Many of us had never been out of Kansas; never seen a large city, or even woods. Both are in short supply in the Jayhawker state. We were to travel by van, but on the morning of our departure, the hubbub was high as we piled in provisions and ourselves. Unfortunately, it bubbled over into the most juvenile of deportments. Driving out of town, we wrote signs and affixed them to the van’s windows: “Pennsylvania or Bust.” “Kiss us; we’re Catholic.” I admit, those two were puerile, and the third was downright stupid. “Help, we’re being kidnapped.” But Father Charles had a great sense of humor. I knew he’d get a kick out of the one about kidnapping. He did. He certainly did.

It was a four hour drive out of central Kansas, and by the time we passed through a toll plaza, east of Topeka, we had long since forgotten the signs. The ones on the side of the van had fallen from place. The one in the back of the van, behind the luggage, hadn’t.

We weren’t long out the toll plaza when a Kansas highway patrol car, lights and sirens fulgent, pulled us over. By that time Mike was driving. We jeered, because we had already agreed that speeders would pay their own ticket. Everyone stopped laughing, however, when Mike, looked back, outside the van, and reported, “He’s pointing a gun at me.”

“What? This must be some mistake.” Father Charles said. My relief was immediate. Father Charles was the Ward Cleaver of Capuchins. If anyone could clear up this confusion, he could. I helpfully added, “They probably think it’s a van with drugs. Won’t they be embarrassed when they realize that they’ve pulled over seminarians and a priest!

Mike exited the van, obeying the gestures of the officer with the gun. Actually there were two officers with guns drawn. Another was kneeling behind the open door of the cruiser. The first officer told Mike to lie on the ground, arms behind his head. Just then a second cruiser came flying in from the opposite direction. It whirled ninety degrees to a stop. Two more officers; two more drawn guns.

“This is ridiculous, Father Charles said. He got out of the van.

“Good, I thought.” Father Cleaver will have this rectified in no time. But they threw—and I do mean threw—Father Charles to the ground. I think he learned an important lesson that day, one about priests not wearing T-shirts when travelling.

There was intense talk outside the van, most of which we couldn’t hear. Inside, no one said a word. The van door slid open from the outside. I can’t recall the face. Only the dark blue hat, its encircling gold cording, the black leather strap across the iron, lighter blue chest, and the stentorian, terribly serious voice that said, much too slowly, “Which one of you boys put that sign in the window?”

I’d like to report that I bravely owned up. Actually, I whimpered and wiggled my hand, ever so slightly.

“Get out.” He said, and I did.

“Come back here.” Walked as fast as my knocking knees would permit.

“What does that sign say?”

Tremulously, “Help, we’re being kidnapped.”

“Are you?”

“No. Not really.”

“Not really? Do you know that the false report of a kidnapping is a federal offense?” I did not know this. To my embarrassment, I knew very little about federal offenses.

“Do you know that I can arrest you right now?” Didn’t know that either, but I certainly didn’t doubt it. My immediate fear was doing time in Topeka, all by my lonesome, while the others visited the East Coast. That didn’t happen, evidently because the officer also understood that reform follows recognition, that realization can lead to repair.

I do not remember them allowing Father Charles and Mike to stand up. I don’t remember the conversation that followed, only the buzz of the cruiser’s radio, verifying the van’s registration.

Released from custody and back in the van, we drove deep into Missouri before anyone spoke. Father Charles clutched the steering wheel like it was a life saver.

Finally, “Father Charles? Are you mad at me?”

“Mad? No. Mad...is…not...the…word. I’m not sure what words I want. Let’s just drive.”

If holiness is the great goal of human life, the only real and lasting fulfillment it can know, then our great advantage as Christians—say, over those post-Christians who are spiritual but not religious—a reason for our hope, is, quite ironically, our awareness of sin. We know that something is broken, missing, or hurting in our life. The church calls it Original Sin and Personal Sin, and being able to name it is already cause for hope, because you cannot reform what you don’t recognize, can’t repair what stands beyond realization.

Donna Tartt, one of my favorite authors, ends her new novel The Goldfinch, with this reflection by her morally compromised protagonist. It’s a great attestation of what we would call Original Sin.

A great sorrow, and one that I am only beginning to understand: we don’t get to choose our own hearts. We can’t make ourselves want what’s good for us or what’s good for other people. We don’t get to choose the people we are.

Because—isn’t it drilled into us constantly, from childhood on, an unquestioned platitude in the culture—? From William Blake to Lady Gaga, from Rousseau to Rumi to Tosca to Mister Rogers, it’s a curiously uniform message, accepted from high to low: when in doubt, what to do? How do we know what’s right for us? Every shrink, every career counselor, every Disney Princess knows the answer: “Be yourself.” “Follow your heart.”

Only here’s what I really, really want someone to explain to me. What if one happens to be possessed of heart that can’t be trusted—? What if the heart, for its own unfathomable reasons, leads one to willfully and in cloud of unspeakable radiance away from health, domesticity, civic responsibility and a strong social connection and the blandly-held common virtues and instead straight towards a beautiful flare of ruin, self-immolation, disaster? (761)

The spirituality of contemporary culture isn’t new, only repackaged. “Be yourself” was a grand Gnostic slogan, but the reality is that our selves are wounded, hurting.

Salvation begins in recognizing the need to be saved. Ironically, the first reason for our hope is our knowledge that something is wrong with the world. Our souls wheeze in its dust. They’re willing to look up, because some light (of grace) makes dingy what, before, only seemed domestic.

Saint Paul told the Corinthians, “For the wisdom of this world is foolishness in the eyes of God, for it is written: God catches the wise in their own ruses” (1 Cor 3:19). God does indeed, sometimes with the aid of the Kansas Highway Patrol.

Leviticus 19: 1-2, 17-18 1 Corinthians 3: 16-23 Matthew 5: 38-48