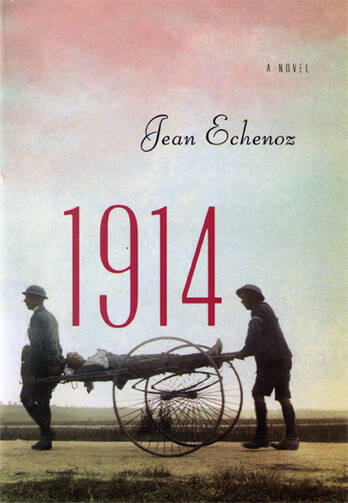

At the start of Jean Echenoz’s beguiling novel, entitled only 1914, a young boy named Anthime rides his bicycle on windy hills above his home. From there he can see his village and several others.

Then, as abruptly as it had begun, the pervasive rumbling of the wind suddenly gave way to the noise it had masked until that moment: up in those church towers, the bells had in fact begun tolling all together, ringing out in a somber, heavy, and threatening disorder in which Anthime, although still too young to have attended many funerals, instinctively recognized the timbre of the tocsin, rung only rarely, the image of which had reached him separately before the sound.

The tocsin, given the world situation at the time could mean only one thing: mobilization (3-4).

It is a Saturday in August, at the height of what would be remembered as the most beautiful of summers. It is the beginning of the First World War. The conflict would call to arms more than 70 million men, and make casualties of 45 million of them. At least nine million combatants died in the war. That’s 230 soldiers, sailors and airmen for every hour it lasted.

Yet here’s the scene in the novel that follows the somber tolling of the bells:

Entering the town, Anthime began to see people leaving their houses to gather in groups before converging on the Place Royale. The men seemed excited, on edge in the heat, turning to call to one another, gesturing broadly but with seeming confidence. Anthime dropped off his bicycle at home before joining the general movement now flowing from every direction toward the main square, where a smiling crowd milled around waving bottles and flags, gesticulating, dashing about, leaving barely enough space for the horse-drawn vehicles already laden with passengers. Everyone appeared well pleased with the mobilization in a hubbub of feverish debates, hearty laughter, hymns, fanfares, and patriotic exclamations punctuated by the neighing of horses (4-5).

The novel’s opening accurately captures the distance between our shallow expectations and, in this case, their ghastly fulfillment. We always overestimate our powers of comprehension. We think the small picture, the image we carry in our minds, adequately corresponds to the world in front of us. We arrogantly believe we know the meaning of war, or, for that matter, of any given event, of another person. We make the same mistake with God. We presume that the utter mystery from which all things came, the very mind of the cosmos, can be reduced to our religious routines, our feeble images.

Writing at the end of the First World War, when humanity’s self-confidence was doubled-over in grief, this was the reminder the Protestant theologian Karl Barth offered to the world, the great “nein” the Swiss pastor shouted. Our minds cannot capture God; our rituals cannot regulate God’s Spirit.

Barth saw Catholicism as a particular offender against God’s transcendence, chiding its belief in what Saint Thomas Aquinas would have called an analogy of being, that, because we come from God, there is some similarity between us and God. For Barth there was only one analogy, one likeness, which he would admit, an analogy of faith. We can believe and trust only what has been revealed in Christ, and even that we fail to comprehend.

Barth’s charge against Catholicism might be valid without the presence of the Holy Spirit in the Church, the one whom Jesus called “the other advocate, ” the one who would come to us and who would remain with us,

Yes, there is a tendency within us to prune everything to our perspective, to fix idols of what is no more than passing comprehension. It’s more than a Catholic failing. Fundamentalists do the same with Sacred Scripture.

But there is also within us a restless drive to know more, to see more keenly, to live tomorrow more fully than today. Barth is certainly right that the power of sin makes us complacent. It narrows our vision. But an advocate, another who is not us, communes with us, deep within our souls. A Spirit hovered over the dark waters of creation; Christ was conceived by the same; and a swift and subtle Spirit still moves within and around us. “The Holy Ghost over the bent world broods with warm breast and with ah! bright wings.”

We stand a century from the start of the First World War, yet, with shallow songs of honor and pride, we still send our young people off to die. Is there any reason to believe in a better tomorrow, given how little we learn?

We read in 1st Peter,

Our hope is humanity’s second advocate before the Father, the Holy Spirit. The Spirit is more than a personification human hope, just as Christ is more than teacher. Both are God, the eternal mystery that enters our history.

A century ago, in the summer of 1914, the spread of science, education, and democracy filled the world with optimism. We had surety aplenty. What we needed, what we still need, is a savior.

Acts 8: 5-8, 14-17 1 Peter 3: 15-18 John 14: 15-21