I have been covering religion stories for PBS-TV for nearly 15 years. Every once in a while I feel as though I am witnessing a miracle unfold. By that I mean, those occasions when I am fortunate enough to see people achieve something truly extraordinary that I can only attribute to a blending of the human will and the work of the Spirit.

I had just such a reaction when I went visited St. Benedict’s Preparatory School in Newark, N.J.’s inner city. I first heard about the school from Dr. Eileen Poiani at my undergraduate alma mater, St. Peter’s University in Jersey City. The filmmakers Marylou and Jerome Bongiorno, fellow St. Peter’s graduates, had produced a documentary on St. Benedict’s as part of a trilogy on their hometown. The segment I reported on the school aired on PBS-TV’s “Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly” last spring.

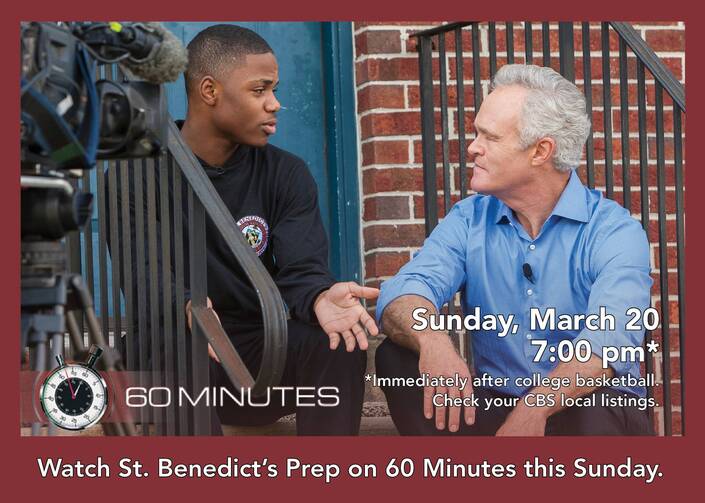

Now this extraordinary school run by 13 Benedictine monks will be the subject of a profile Sunday March 20th on CBS-TV’s “60 Minutes.”

St. Benedict’s all-male student body is 80 percent African American and Latino. Most of the students come from fatherless homes and neighborhoods that are prey to many of the social ills plaguing this city: high unemployment, routine violence and low-performing schools. St. Benedict’s has a near-perfect graduation rate. Ninety-five percent of last year’s senior class went on to college.

The secret to St. Benedict’s success? It operates more like a monastery than a school. The main subject taught there is community.

“With young people, I believe it’s important to educate them in community, in connectedness,” says headmaster Father Edwin Leahy, a monk who looks much younger than his 69 years.

Signs throughout hallways remind students of the school’s motto: “Whoever Hurts My Brother Hurts Me.” Father Leahy says, “We try to get kids to understand that, to live that.”

It is something he too had to learn during nearly 50 years of monastic life, where he admits it isn’t always easy to live in community with people of varying personalities and backgrounds.

“There are days when you when you get the realization as you look across the choir [during the daily Liturgy of the Hours] that that’s the same person—even though he may grate on me—that’s likely to be singing in the heavenly choir right across from me, right?”

Unlike other Catholic academies, St. Benedict’s is in session 11 months of the year. Father Leahy, himself an alumnus of an earlier incarnation of the school, jokingly compares it to a “24-hour diner.”

St. Benedict’s is a school that almost wasn’t. It was founded in 1848 to educate the sons of upwardly mobile Italian, Irish, and German Americans. When the race riots of 1967 drove many white families from Newark, the school’s student body dwindled.

“The National Guard was right on the street in front of the abbey,” Father Leahy recalls. The monks watched from the rooftop as buildings around the city went up in smoke. St. Benedict’s closed for a year. A third of the monks transferred to another monastery in a more sedate and upscale community. A corps, including Father Leahy, remained behind determined to revive the school. The Benedictine vow of stability, a feature of monastic life since the 5th century, was an important consideration for the monks who stayed.

“We’re here as a sign of God’s presence,” Father Leahy says. “Benedictines tend to be a big tap root. We’ve got a root that goes down pretty deep and when you get to a place, it’s not easy to leave it. That’s kind of who we are as monks. We take a vow of stability of place, so even though the neighborhoods around us change, we stay.”

At 9:15 every morning, the entire school gathers for a convocation the students affectionately refer to as “convo.” The color-coordinated sweat shirts they wear identify them by class year. Class leaders report on attendance and discuss upcoming activities. Then, in a practice similar to a monastic chapter meeting, students have a chance to bring up what’s on their minds. And in the centuries old tradition of the Opus Dei, the teens begin their day by singing a hymn, followed by the prayers for Lauds.

In terms of a physical campus, St. Benedict’s would rank with the best of preparatory schools. It has an Olympic-size pool, two gyms and a large theater where student productions are staged. But few can afford to pay the annual $12,500 tuition. The school raises about $6 million each year through alumni donations and grants from corporations and area financial institutions.

Violence occurs daily in the neighborhoods where many of the students live. But at the school, there are no security cameras, metal detectors or even locks on individual lockers. The emphasis is on personal responsibility.

“So many times in schools, they’re run so heavily from the top down. I don’t believe that’s helpful to kids, especially young men of color because so much of their life they feel they have no control over,” Father Leahy says. “One of the most important advice anyone ever gave me was to take the cotton out of my ears and stick it in my mouth. To just shut up and listen. We manage to do that a little bit and people taught us how we could be of help them.”

Much of the school’s philosophy is based on the 1,600-year-old guide to monastic living, The Rule of St. Benedict.

“In terms of silence and in terms of relationship with God and community and forgiveness, there is a lot in there that resonates” with students, says Father Augustine Curley, who teaches a class on monastic principles. “It’s always amazing when they finally look at The Rule and they say, ‘Oh, that’s why we do that here.’”

Students who commit serious infractions aren’t suspended or expelled. Taking a page directly out of The Rule, the students are “excommunicated” for a time from practices within the school community.

“You’re not allowed to come to the morning meeting, you’re not allowed to eat in the cafeteria with everybody. We’re trying to get them to reflect on their inappropriate behavior within the context of the community, so you take them out of the community,” Father Leahy says.

When Jaheer Jones, an otherwise stellar student, got into an uncharacteristic fight with another student, Father Leahy required him to assist him in setting up for Mass on Saturday nights and participate in a Bible study.

“For me, it was a period of like, self-realization,” Jones says. “So while, yeah, I was learning things about the Bible, things like that, I was also learning how it could affect my life.”

Like most of St. Benedict’s 536 students, Jones isn’t Catholic. He’s a Pentecostal Protestant. His mother, Selma Daniels, says she welcomes the school’s emphasis on Catholic monastic practices.

“The relationship that the monks have with the students, I like. I like the way they talk to them, I like the way they treat them, give them a sense of community and a sense really of hope,” she says.

Muqka Poole was encouraged to apply to St. Benedict’s by a cousin who graduate from the school and went on to college.

“Going to college isn’t something I’m used to or my family is used to,” Pools says. His cousin told him, “Muqka, you’ve got to go there. You’ve got to go to St. Benedict’s.”

At the time I spoke with him, Poole had already been accepted to St. John’s University in Collegeville, Minn. He is one of 60 students who is able to live on school grounds in a building next to the monastery.

“If I wasn’t living here, to tell you the truth, I’d probably be here at 11:30 at night. My neighborhood is unsafe, it’s dangerous,” Poole told me. He said it has helped him “not to be in a stressful environment” so he could focus on his grades in his senior year.

The school employs several professional counselors, and counseling sessions occur daily, a key part of the core curriculum. For students, having the courage to attend a counseling group is looked upon as more of a badge of honor than something to remain hidden. The “Blues Boys” is a group for students who struggle with depression. “Unknown Sons” is for boys who have little contact with their fathers.

“What we’ve discovered is a lot of what manifests itself outwardly as poor academic performance has very little, if anything, to do with cognition,” Father Leahy says. “I has to do with emotional distress that a young man is going through, so that they turn that turn that anger on themselves and little by little destroy themselves.”

St. Benedict’s can’t always protect its students from negative outside influences. Tyrone Heggins was a student leader who went on to the University of Delaware. Just weeks before his college graduation, he was arrested for armed robbery and went on to serve three years in prison.

“It was devastating for my family and the St. Benedict’s community, and everyone who cared about me and respected me because it was so contrary to my character,” Heggins told me.

Heggins said he participated in the robbery at the urging of some friends he was trying to impress. After he was released from prison, the court expunged his criminal record. He is now married and has a son. He works for a corporation where he’s been placed on a management track. Heggins often returns to the school to counsel students, and still seeks counsel himself from former teachers.

“No matter where I reside in the world, my son doesn’t have a choice of where he is going to school. If I live under a rock in Switzerland, he’s still going to St. Benedict’s,” Heggins says.

Teachers College at New York’s Columbia University has been in touch with Father Leahy about writing a study guide that would use St. Benedict’s methods as a model for urban education. Father Leahy acknowledges it would be hard to replicate St. Benedict’s success without the emphasis on monastic practices and values.

“I think two things are essential,” he says. “Whoever is the head of the school needs to live there, and it needs to be a diner. It needs to be open 24 hours a day, seven days a week. In order to do that, it seems to me you’ve got to have some kind of community present. We have kids show up here at two, three o’clock in the morning for relief of one kind of suffering or another.”

As with most monasteries, few monks have joined Newark Abbey in recent years. There is concern about what will happen to the school if the monastic community continues to shrink. And, raising $6 million a year is always a struggle. Father Leahy says he doesn’t spend too much time worrying.

“When we get to June 30th and we make it, we all rejoice. Then we know we have to do it all again. All I can hear is the voice of the Lord to Moses saying, ‘Go forward. Don’t stop, and a way will open. That’s what I’m trying to do. That’s what my brothers in the monastery are trying to do, and that’s what we try to get the kids to do. Just walk, and God will lead you to the place where God wants you.”

In the end, Father Leahy says it’s all about teaching these young men that their lives have meaning. As long as a single monk is left, Father Leahy says St. Benedict’s will keep carrying that mission forward.