In the Gospel of John, Jesus tells the sympathetic Pharisee Nicodemus: “The wind blows where it wills, and you can hear the sound it makes, but you do not know where it comes from or where it goes; so it is with everyone who is born of the Spirit” (Jn 3:8). This metaphor is meant to explain an earlier statement: that in order to enter the kingdom of God, one must be reborn in the Spirit. Nicodemus is puzzled, and so Jesus uses this image to explain that to those still “of the world,” the ways of those reborn in the Spirit will be as mysterious as the movements of the wind.

This same verse (albeit from a different translation of the Bible) figures prominently in Robert Bresson’s 1956 prison break drama, “A Man Escaped.” French Resistance fighter Lieutenant Fontaine (François Leterrier) is arrested by the Nazis and confined to Montluc Prison. Here the conflict between world and Spirit is literalized: the former embodied by the Nazi jailers, the latter by Fontaine and his relentless quest for freedom. It’s a story of a man seeking temporal salvation (Fontaine knows that his execution is imminent) but through Bresson’s sparse, methodical style the film takes on deeper meaning, becoming a parable of the Spirit.

One of the most influential figures in French cinema, Bresson was known for the simplicity of his filmmaking. “A Man Escaped” makes minimal use of sets, score and dialogue. The cast is largely made up of non-professional actors, another Bresson trademark, lending the performances a quiet authenticity. A former prisoner of war himself, Bresson offers a worldview that can sometimes seem as stark as his set dressing. But he was also a Catholic, and his films explore the tension of the promise of the Resurrection in a fallen, violent world.

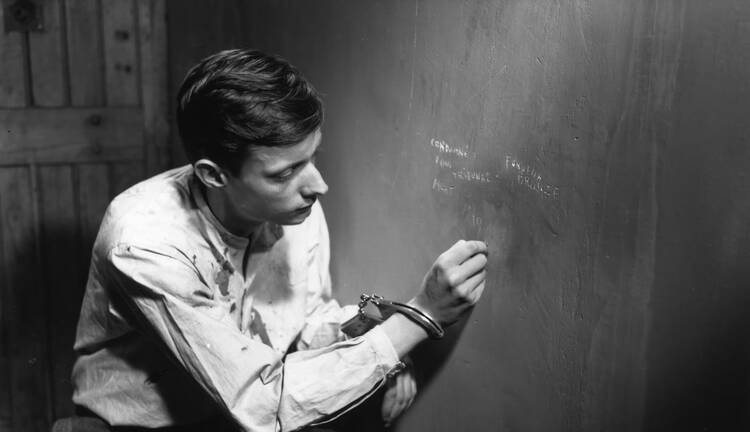

For Fontaine, the promise of freedom is synonymous with new life, and it inspires him to persevere despite the many obstacles he faces. In the opening moments of the film, he attempts to escape from the car that is transporting him to prison. He is recaptured and beaten savagely, his clothes streaked with blood that will remain for the rest of the movie. Afterwards he allows his guards to think that he is broken, but in truth his resolve is only strengthened. We follow his plan for escape in minute detail, watching him slowly work away at the boards in his door with a sharpened spoon. That might not sound exciting, but Bresson fills those moments with incredible tension—and a meditative potency that makes them feel like a sort of urgent prayer.

For Fontaine, his desire to escape isn’t merely about saving his life: it’s a desire to resist the violent, oppressive power of the world and reject its attempts to control him. With only the barest of resources, he and his fellow prisoners resist in small ways: whispered words during the few minutes a day that they see each other, tapped messages on shared cell walls. When Fontaine finally removes the boards from his door, he uses his first brief foray out of his cell to encourage another man receiving a harsher penalty, letting him know he’s not alone. The aforementioned verse from John is another example: an imprisoned pastor (Roland Monod) writes it on a scrap of paper for Fontaine, words of comfort and strength.

At one point, Fontaine’s neighbor, Blanchet (Maurice Beerblock), asks why he bothers when the situation appears so hopeless. Fontaine responds: “To fight. To fight the walls, to fight myself, to fight the door. You too, Mr. Blanchet, should fight and hope.”

That’s something that their jailers—so confident in the brutal power of the world—could never understand. Fontaine is driven by a transcendent hope and an indomitable spirit, but his plans are also helped by the fact that the Nazis underestimate him. Of course: they easily traded their humanity for a chance at security and power. They assume Fontaine’s spirit will be broken by his trials because they sold their souls so cheaply.

This is not to say that Fontaine never wavers. There are several times where he drifts close to despair, or hesitates out of fear. When he is given a new cellmate, the young deserter Jost (Charles Le Clainche), he faces his ultimate test of faith: Will he entrust his plans to this possibly untrustworthy newcomer, or kill him in an act of brutal necessity? In essence, it’s a choice between the cold logic of the world and the radical hope of the Spirit. Fontaine makes his choice, and we are left to make ours.

“A Man Escaped” is streaming on the Criterion Channel.