Every Sunday morning at about 8 a.m., my mom and dad would load their three boys into a minivan, passing by a dozen or so other Catholic churches on our 20-minute drive up Route 1 to meet my grandparents for 8:30 Mass. We always gave our grandfather a kiss as we passed him sitting in the church’s rear with the other ushers before joining “Mom-Mom” in her pew. I imagine they’d taken the same seats since arriving in the United States in 1955.

Once Mass ended, our family would drive or walk the few short blocks to my great-grandparents’ house for a short visit. Prevented from attending Mass by Pop’s emphysema, Nonna would have used the time to prepare coffee and a platter of S-shaped cookies. At midday, we gathered at my grandparents’ home with extended family for a traditional Italian Sunday meal.

This routine was the drumbeat that set the rhythm for my life. I substitute the drumstick for my grandmother’s wooden spoon—usually stirring, occasionally menacing, but always producing the meal that was a coda to a week of school and sports and to the day devoted to my faith and my family. Faith shaped my family’s habits, which in turn shaped my own.

As I have grown older, this has developed into something approximating a morality that informs how I approach my roles as a husband, as a father and even as a citizen—a code that grounds my daily choices in something that feels ancient. I credit this foundation for my decision to serve in the Marine Corps, to stay active in my community and to take on my current role as the executive director of More in Common, an organization dedicated to reducing polarization in American society.

Religious resurgence?

In search of the same grounding for our children, my wife and I moved back to my hometown a few years ago, where we go to that same church and sit in the same pew. I expected the pews to be emptier than they were three decades ago, the seats filled by many of the same people who were there when I was a child. I was surprised to find the church full, with many young families in attendance.

Our tiny church in central New Jersey has begun to fill up more and more in the years since we moved home, a phenomenon that matches a trend I have noticed in my daily life. In a culture that, outside of my family and a few close friends, had seemed overwhelmingly secular, I began to notice that both religiosity, generally, and faith in God specifically, have become more commonplace. In the liberal, Ivy League community where we live, many of our children’s friends from public school attend Mass with us, and we’ve come to know many other families who attend other religious services regularly. At work dinners and social events where a handful of years ago discussing faith would have seemed out of place, religion has become a more regular topic of conversation, and personal faith a point of shared pride rather than an object of fascination.

Yet as I look to the broader culture, this blend of faith, family, morality and citizenship still feels anachronistic. Unlike a decade or two ago, I do not see a culture that mocks faith but a culture that views faith through a partisan political lens. The national conversation about faith has been reduced to Catholics’ views on abortion or the recent conversion of some celebrity right-wing political figures to our faith; to evangelicals’ alignment with Donald J. Trump; to how Democrats can try to balance a coalition that includes important swing-state blocs of Jewish and Muslim voters, and so on.

‘Collateral contempt’

More in Common, which I have led since this May, recently released the report “Promising Revelations: Undoing the False Impressions of America’s Faithful.” In a survey of 6,000 Americans, the report dispels three core myths: that faith is all about politics; that faith is becoming irrelevant in Americans’ lives; and that religious Americans are intolerant. For this piece, I will focus on the first of those three myths—and the harm that it does to the power of faith as an American institution.

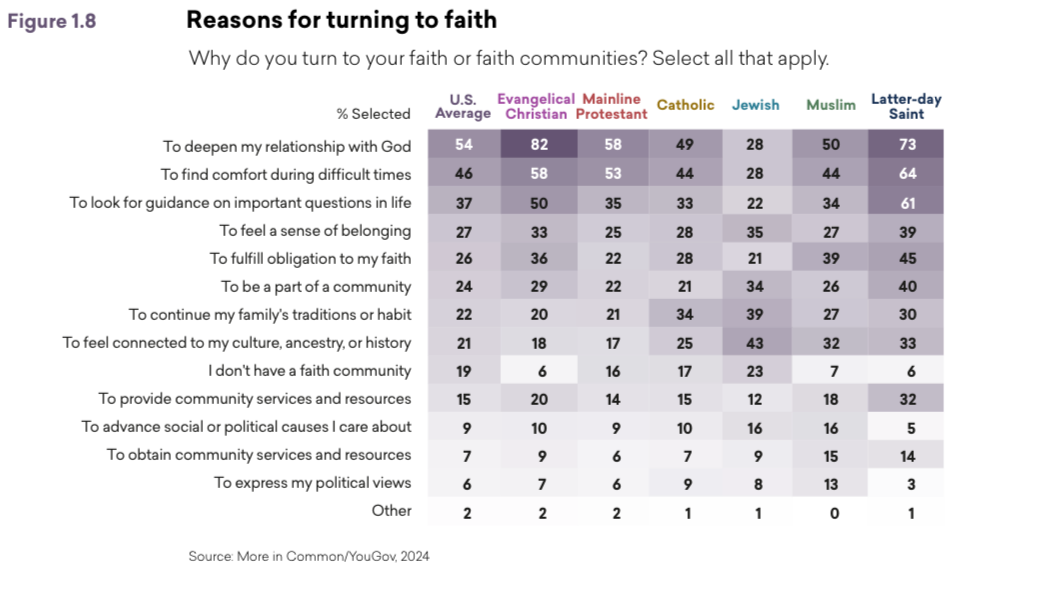

As it turns out, most Americans turn to faith for the same reasons I do—for moral formation, for community and to cultivate their relationship with God. While around half of Americans feel that their religion influences their political views, only 6 percent of Americans turn to faith to express their political views, compared to 54 percent to deepen their relationship with God, 24 percent to be a part of a community and 22 percent to continue family traditions.

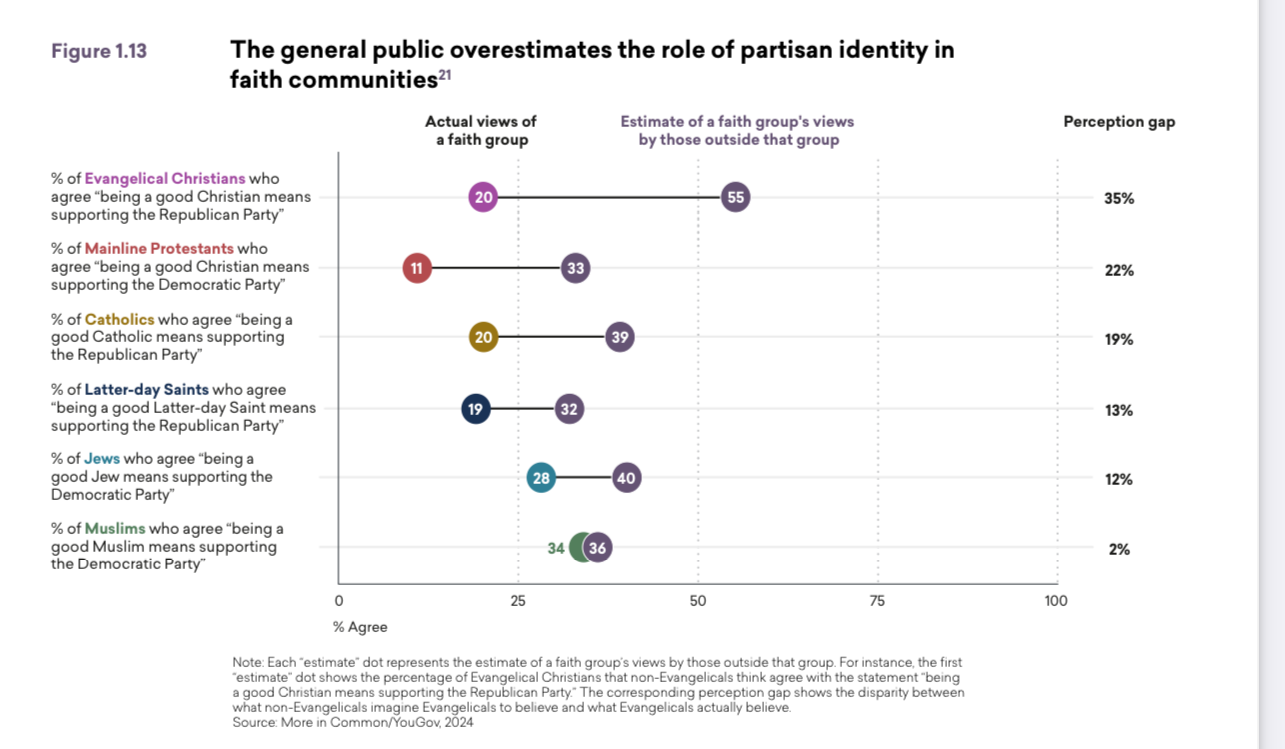

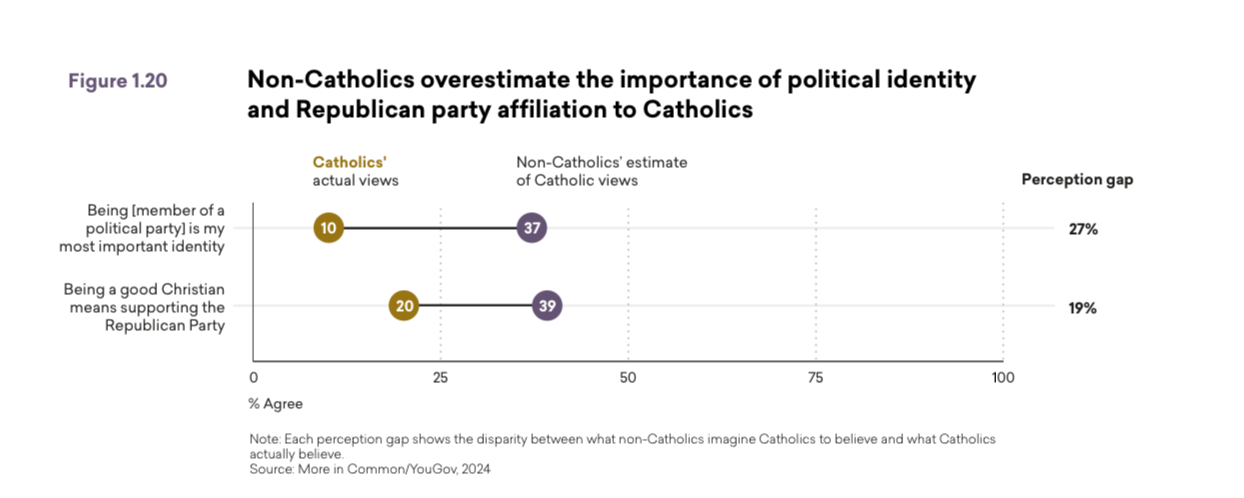

Far more Americans think that faith is all about politics than is the case. When asked if being a member of a political party is their most important identity, only 4 percent of evangelicals and 10 percent of Catholics agree, whereas the general public estimates that 41 percent of evangelicals and 37 percent of Catholics hold these views. (Catholics report that their family role is their most important identity, while evangelicals report that their religion is their most important identity.)

These misperceptions extend to partisan politics as well. Americans estimate that 39 percent of Catholics and 55 percent of evangelicals would agree that “being a good Catholic (or Christian) means supporting the Republican Party,” while only 20 percent of both Catholics and evangelicals agree with this sentiment.

This misperception of the faith institutions that form our character and shape our views of citizenship as mere political instruments is corrosive to our national dialogue and cohesion. The more negatively non-Catholics and non-evangelicals feel toward Catholics and evangelicals, the greater their misperceptions about the importance of politics and partisan identity within each faith group. We call this collateral contempt—the tendency for animosity toward political opponents to spill over to religious groups that are perceived (but in point of fact are not) exclusively aligned with one political team.

This does not neglect the fact that evangelicals and to a lesser extent Catholics, for instance, have tended to vote for Republicans. Nor does it excuse from scrutiny the faithful who have deprioritized personal morality when casting votes for President Trump. It merely highlights that we mistake the church for being a political arena when it is not. Viewing faith through an exclusively partisan lens corrupts the power of belief and its attendant institutions to mold citizens.

In Democracy in America, his seminal 19th-century study of the American character, Alexis de Tocqueville observed:

It is when [religion] does not speak of freedom that it best teaches Americans the art of being free. There is an innumerable multitude of sects in the United States. All differ in the worship one must render to the Creator, but all agree on the duties of men toward one another…. Religion, which, among Americans, never mixes directly in the government of society, should therefore be considered as the first of their political institutions; for if it does not give them the taste for freedom, it singularly facilitates their use of it.

Faith and faith communities are more beautiful than partisan warfare, and the morals they cultivate more essential to believers. JD Vance, one of the most prominent right-leaning politicians to have converted to Catholicism, points to this in an essay about his personal conversion: “The Church isn’t just about ideas and Saint Augustine, whom I chose as my patron. It’s about the heart, as well, and the community of believers. It’s about going to Mass and receiving the Sacraments, even when it’s difficult or awkward to do so.”

A few weeks ago, my grandparents, now in their late 80s, stopped attending Mass due to my grandmother’s debilitating Alzheimer’s. It is heart-wrenching, but also confirms what I knew when we moved home: that my children would be the last link in the chain, connecting my family who had grown up kneeling in Italian churches to those who had crossed an ocean to participate in the same ancient traditions in a new world. I make the Sunday dinner now, and pray that my own wooden spoon gives my children and their children and their children the same gifts it has given me.