We seem to have found ourselves in a time of strongmen—when masses of people, in many countries, rally around leaders who offer to wield force on their behalf, who defy institutions and processes and uncertainties, who promise some form of salvation. Christian faith, too, rests on a salvific promise, though it can be tricky to discern whether that salvation has anything to do with what the strongmen offer. Who wouldn’t want to be saved?

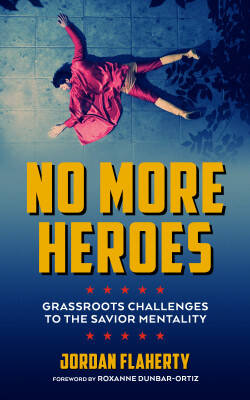

Jordan Flaherty, a veteran journalist, has written a book for times like these, published just this month. No More Heroes: Grassroots Challenges to the Savior Mentality confronts the appeal that many kinds of salvation stories hold—both for the people they claim to save and the prospective saviors themselves. The book takes aim at populist authoritarians and idealistic humanitarians alike. I asked Mr. Flaherty about where the book came from and what it means for us now.

Tell us: What does the “savior mentality” mean to you, and why did you consider it worth writing a book about?

Simply put, the savior mentality is the idea that a hero will come and answer our societal problems, like Superman saving Lois Lane or a firefighter rescuing a kitten from a tree. From the “great man” theory of history—the idea that history is shaped by individuals rather than movements or ideas—through modern projects like Save Darfur, or law enforcement claiming they are "saving" sex workers by arresting them or travel agencies pitching “voluntourism.” When you look at change throughout history, and when you talk to the individuals supposedly “saved” in these modern efforts, you find that real change is not so simple or easy as rebranding your vacation.

I work as a journalist, and reporting around the world I kept seeing similar conflicts coming up in very different struggles. Generally, people on every side of an issue feel that they are doing good, that they have the answer. On education reform, for example, everyone says they have the same goals; the best education for the greatest number of students. The difference, I have found, is often if they think of change on individual or systemic levels. This book explores how those different models of change play out, through personal stories and on-the-ground investigations.

Early in the book, you identify the origins of the savior mentality with the Crusades. I am not sure I agree that is historically apt since the Muslim powers constituted an active military and cultural threat to Western Europe—and in many ways a more advanced one—as much as it was a mission field. But do you consider saviorism a wholly Christian construct, or does it appear in other cultural lineages as well?

This book is a combination of history, journalism and memoir, often drawing out connections between historical events and the modern era. I do begin with the Crusades, and I think it's a useful starting point, but that doesn't mean that the idea of saviors started there, or that it is unique to Christianity. I think that framing the story with the Crusades is useful for some of the later stories in the book, from George W. Bush referring to the “war on terror” as a crusade, to the missionary roots of the KONY 2012 campaign. It's also a useful story of war and violence cloaked in the language of help.

Where do you see the savior mentality showing up most in the world today?

I think in the most literal sense we see it coming from Hollywood, and popular culture overall, and that helps push it into the rest of our society. This book explores not just superhero movies but the ways in which supposedly progressive movies, like the pro-union film “Norma Rae,” push this dynamic. We also see it taught in our schools, which of course also shapes us. And from there, I think even progressives, who may be politically critical of this model, end up almost unconsciously supporting it because we've been surrounded by it all of our lives. It's a compelling story; who doesn't want a simple solution?

Where do you see alternatives to the figure of the savior?

This book tells the stories of activists and organizations who are making real change, people like Black trans sex-worker activist Monica Jones, white queer organizer Caitlin Breedlove, indigenous activists and their allies fighting for environmental justice and many more, from the Arab Spring to Black Lives Matter. This book was an exciting opportunity for me to speak to people—like the Black Lives Matter founders, activists in Egypt and Palestine and many more—who have been thinking about these issues for a long time and have found ways to really create lasting change.

It seems like the difference here is that the people leading these struggles are not outsiders charging in but the people most affected. Is that right? How, then, can outsiders support such efforts without embracing saviorism?

A lot of the book deals with this crucial question. Caitlin Breedlove, a brilliant activist and white ally, recommends several great questions to ask ourselves, including, “What are the actions for social justice and movement building that don’t center you as a protagonist?” Catalyst Project, an anti-racism training organization in California, recommends that white activists organize other white people in support of people of color-led movements, asking, “How can we find ways to bring more and more people into social justice work, from lots of entry points, to grow vibrant mass movements?”

I'm also really influenced by the Zapatistas, who popularized the saying, “Walking, we ask questions.” In other words, don’t be so afraid to take action that you are immobilized. But, as you take action, listen to the voices of those most affected, and be ready to change course based on their feedback.

I keep hearing the words from an acclamation in the Catholic Mass, “Save us, savior of the world.” They still seem beautiful to me. Is there anything to be redeemed in the figure of the savior, in your view?

The desire to save the world, the desire to help others, the desire for change, all of these are beautiful. And I think we all know what it feels like to want to be rescued. Most people that I identify as “saviors” in the book are people driven by a desire to do good. But life is about more than intentions—it’s also about impact. I support whatever motivation guides people to want change. This book is a tool for those who want a better world, to help them make that change concrete.

I guess for me the beauty in that phrase comes from the humility in recognizing that I can't save myself or anyone else, that hope comes from such unexpected places as a marginal artisan executed by the state. I wonder if this has anything in common with looking to the marginalized as agents of change.

Definitely. That’s a powerful connection to make.

Do you see in President-elect Trump the image of a savior? Or something else? In some ways, I think part of his appeal is the way in which he has spent his life mainly looking after himself—not engaged in selfless public service as some kind of savior. Could his rise be an expression of savior fatigue?

The themes of this book are reflected in the election in many ways. I do think many Trump supporters see him as a kind of savior, and that craving for a savior caused some of them to ignore evidence of what he represents.

The book is also critical of celebrity culture and the failures of corporate journalism, and I think this election was the clearest case study in how our media has failed our society. I believe most people in the media wanted Trump to lose, but they also wanted to chase the ratings they would get from giving him airtime—and that greed won out, giving him an estimated $2 billion of free exposure. And even when journalists were critical of him, they were likely to make fun of him as delusional, or just endlessly discuss the latest polls, rather than do real investigative reporting.

This book is also critical of settling for small reforms when major structural changes are needed, which is the kind of thinking that brings us losing Democratic Party candidates, from Kerry to Hillary. Finally, my hope is this book charts a path forward, providing concrete examples of ways in which people have successfully organized in repressive environments. Something that's sadly all-too-relevant now.

Such a great favor from cool mathematics games of your blog to spread the content.

This is the first time I have come across this site and it is interesting to read about the latest news on the American magazine. I really like this site because it offers posts from politics, arts, culture etc. The magazine was really interesting and please update with more topics.CCCHC free hiv testing