The very title of Pope Saint John Paul II’s 2003 encyclical “Ecclesia de Eucharistia” (“The Church of the Eucharist”) tells us clearly that the Eucharist is at the heart of who we are as Catholics and what we do. We are a community of believers formed by the Eucharist to bring the mission of Jesus Christ forward in the world and throughout history.

In every age, we need to pay close attention to the Eucharist. This is all the truer when we live in a markedly complex and not always clear Eucharistic landscape. Many graces linked to the Eucharist mark our time—but so do some significant challenges.

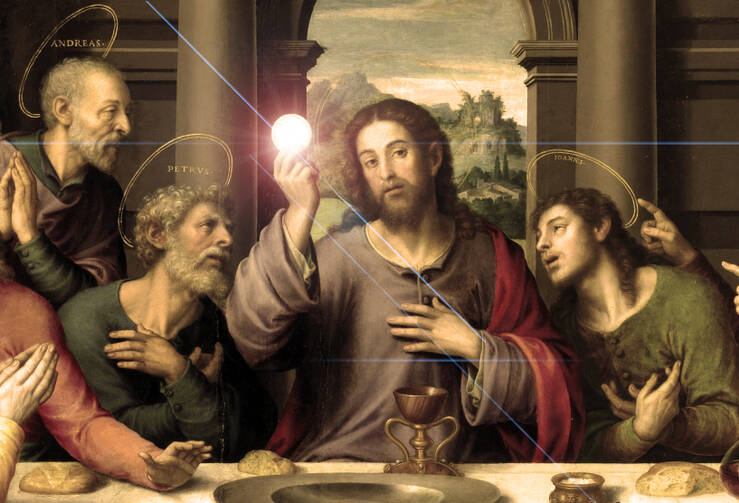

The Eucharistic landscape has, in some measure, been a complex one throughout Christian history, one with both graces and challenges. In the New Testament, for example, we see the Eucharistic grace of experiencing Jesus as the Bread of Life (see John 6) and of sharing communion with him and one another in the one bread and the one cup (1 Cor 10:16-17). The Eucharist also carries the grace of eternal life (see John 6:50-51) or, in the words of the Greek fathers, “the medicine of immortality.”

Alongside the graces of the Eucharist, the New Testament also gives evidence of Eucharistic challenges. More specifically, the Scriptures point to instances of Eucharistic inconsistency; a mismatch between the truth of the Eucharist and the way its meaning is lived out. In Luke’s account of the Last Supper (Lk 22), for instance, Jesus institutes the Eucharist; immediately afterward, we are told: “A dispute arose among them as to which of them was to be regarded as the greatest.”

Eucharistic inconsistency is also evident in Paul’s letters, especially within his beloved and gifted Corinthian community. Paul admonishes them:

When you come together, it is not really to eat the Lord’s supper. For when the time comes to eat, each of you goes ahead with your own supper, and one goes hungry, and another becomes drunk (1 Cor 11:21).

This controversy moved the early church to make a dramatic change in Eucharistic practice by moving the celebration out of the context of a shared meal. In this decision, we can see that reforms to the Eucharistic celebration—intended to retrieve its original meaning—were part of the church’s life from the beginning.

What are we to make of this? Simply this: In every age—including our own—the church’s complex Eucharistic landscape calls our attention to both its graces and challenges but also invites us to be open to reform, so that we may claim and live the Eucharist more authentically.

Challenges

Among the various Eucharistic challenges in our day, I want to highlight four that, in my estimation, are especially significant.

Participation. Despite an uptick in participation in Sunday Eucharist in recent years, regular participation is still around 20 percent. If what recent popes and the Second Vatican Council have taught about the Eucharist is true—that it is “the source and summit of the Christian life” and “the indispensable resource for the Christian spirit”—then we are bound to ask: “What gives here?”

This lack of participation goes beyond ignoring a church precept—or even the Third Commandment. I am drawn to the observation that Isaac Bashevis Singer made about worship more generally. He asserted that we human beings are bound to worship, and so we will inevitably worship. If we do not worship God, however, we will worship something else, with the saddest prospect being worship of ourselves. So, the lack of Eucharistic participation is really about the first and most fundamental commandment that is at the heart of humanity’s covenant-relationship with God.

Formation. Closely related to the lack of participation is another challenge that helps explain why many do not come to Mass: a lack of coherent and consistent Eucharistic catechesis and formation. This lack is manifested in at least two ways.

First, many have not fully understood that at the core of our belief in the real, sacramental presence of Jesus Christ in the Eucharist is our belief in the Resurrection. In the Eucharistic celebration, the Risen Lord exercises his priestly ministry by making present his victory and triumph over death. This is what we mean when we profess that Christ is really and truly sacramentally present in the Eucharist.

Some polls have suggested that large swaths of Catholics do not believe in the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist. The more likely problem may be a failure to believe and affirm what undergirds that presence—his resurrection. Might this be why some confuse sacramental presence with physical presence? Might it also explain the recent fascination in some quarters with Eucharistic miracles?

Second, another fundamental sign of inadequate Eucharistic formation is not knowing how to fully, consciously and actively participate in the Eucharist. The muted responses, the silent music, the telltale comment—“I didn’t get anything out of it”—are all signals that people have not joined together with their brothers and sisters and with Christ, their priest, in offering their worship to the Father in the Spirit. Symptomatic of this lack of formation in participation is the bewildering range of individual practices and behaviors that suggest people do not know how to enter the liturgy as an act of communal worship, including sauntering in after the Liturgy of the Word, standing and kneeling out of sync with the assembly and receiving Holy Communion with an odd array of postures. All of this suggests the dominance of personal taste or private piety over a sense of corporate worship.

The Traditional Latin Mass. The ongoing matter of the availability of the Traditional Latin Mass remains a significant concern for some priests and for a fair number of Catholics, especially some younger Catholics who find themselves strongly attracted to this form of celebrating the Mass. The challenge resides in bridging and coordinating attachment to this practice with the larger life of the church.

Real tensions, of course, emerged with Pope Francis’ apostolic letter “Traditionis Custodes” and his request that bishops not only restrict the celebration of the Traditional Latin Mass, but also lead people to embrace the liturgical books promulgated by Pope Saint Paul VI and Pope Saint John Paul II—for the unity of the church and as the unique expression of the lex orandi, the church’s officially approved way of praying in the Roman Rite.

Future reflection on the Traditional Latin Mass will also need to consider whether this form of celebration can sustain the vision of a synodal church moving into the future. Put differently, is it more a matter of personal piety rather than a means to sustain and foster our corporate identity as the Body of Christ moving together through history?

Eucharist and Social Commitment. This fourth and final challenge is one easily observed in our Chicago Catholic history. It seems that we have largely lost an important connection that had been especially cultivated in this local church—between the Eucharist and our commitment to social action for justice, peace and the dignity of all life. The great Chicago priest Monsignor Reynold Hillenbrand and others in the 1940s and ’50s sought to launch believers from the liturgy into a world in need of healing and transformation. The fading of this liturgical-social consciousness today reveals a troubling disjunction between the Eucharist we celebrate and the Eucharist we live.

Graces

In addition to Eucharistic challenges, important graces are also a part of our moment. Good and holy things that are happening, We must not overlook them or take them for granted.

The Eucharistic Revival. The yearlong process that culminated with a major national celebration in Indianapolis this past year was a grace for the church in the United States. Many people participated in various aspects of the revival. The whole process may not have been perfect, but in a particular way, it clearly engaged many young people and made a difference in their lives.

Eucharistic adoration and Eucharistic devotions. A second grace has been a rise and renewed interest in Eucharistic adoration. With greater availability in our parishes and other settings, people are taking advantage of adoration to their spiritual benefit. There has also been a growth of communal Eucharistic devotions, such as processions and the celebration of benediction. Many of these devotions are an expression of the diversity of popular religiosity that is a treasure of the church in the United States.

Eucharistic ministers. The presence of well-trained Eucharistic ministers is another significant grace in today’s church. Many serve as Extraordinary Ministers of Holy Communion at Sunday celebrations of the Eucharist. Others are specifically formed and commissioned as “Ministers of Care” to bring the Eucharist to the sick in hospitals and nursing homes and to the homebound. Their ministry is a great blessing.

Well-prepared Eucharistic celebrations. Too often, we take for granted another truly significant grace in the life of the church. It is the investment of our parishes through their priests, deacons and laity in the celebrations of the Eucharist. They prepare for Masses with care and attention. Is it all perfect? Of course not. But it is done with love, and most often done well. Especially commendable is the attention paid to the diversity of languages and cultures in the United States that express the Eucharist as a sign and source of our unity and communion.

Looking ahead

So, what should we do with all this? How should we meet the challenges? How should we accept and deepen the graces?

First, in a synodal church, we ought to talk with and listen to one another. Talking in this context does not mean debating or arguing about liturgy. We need to talk about the Eucharist and our worship so that we can discover together where God is leading us next. Pope Francis’ apostolic letter “Desiderio Desideravi” is an extraordinary resource for this kind of holy conversation. Another helpful guide is a booklet released by Cardinal Blase Cupich: Take, Bless, Break, Share: A Strategy for Eucharistic Revival.

For that synodal conversation about the Eucharist and our worship, it may also be helpful—even necessary—to have a framework for understanding the various dimensions of prayer tied to the Eucharist. In the Eucharist, Jesus Christ makes himself available and accessible to us through his self-sacrificing love and enduring presence to the church. In the Eucharist, the Lord also draws us to the cross to share in his saving work. All this unfolds in our relationship with him, a rich and multi-dimensional relationship with the risen Lord. These relational dimensions come alive in corresponding ways of praying.

Consider, for example, Saint Paul’s deeply personal and intimate relationship with the Lord as he expresses it in Galatians: “I have been crucified with Christ; and it is no longer I who live, but it is Christ who lives in me. And the life I now live in the flesh I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me” (2:19-20). This corresponds exactly to the description of personal prayer that Saint Teresa of Jesus offers in her autobiography: “an intimate sharing between friends; it means taking time frequently to be alone with Him who we know loves us.” It also reflects Eucharistic praying in adoration.

But Paul’s relationship to Jesus is not limited to the personal and intimate. He also relates to Jesus, the Risen One, in and through the community that is his body. So writing to his beloved—and often exasperating—community at Corinth, he says, “Now you are the body of Christ and individually members of it” (1 Cor 11:27). The Eucharistic praying that corresponds to this dimension of the relationship with Jesus is, of course, the corporate prayer of the Eucharistic liturgy. Also included in this dimension are shared Eucharistic devotions and forms of popular piety, especially those that have a particular cultural inflection.

Paul also relates to Jesus Christ as the universal Lord of the cosmos and history. In his letter to the Colossians, he writes: “He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation; for in him all things in heaven and on earth were created…in him all things hold together…for in him all the fullness (pleroma) of God was pleased to dwell…” (Col. 1:15, 17, 19). The Eucharistic praying that corresponds to our relationship with Jesus the universal Lord of the cosmos and history is, of course, the Eucharistic liturgy which links heaven and earth and connects all history to the one Lord who is its goal.

Unless these different dimensions of Eucharistic praying are differentiated—and each one respected and valued for its specific contribution to our life in Christ—confusion will ensue. And it has. Many of the tensions in the complex Eucharistic landscape that I described earlier occur because of a mix-up of different ways of Eucharistic praying.

For example, the preferences of one’s personal piety are not a reliable source to direct our participation in the Eucharistic liturgy. Because the liturgy is corporate worship, our posture, our responses and our attention join those of others in an active and conscious experience that both is communal and expresses our belonging to the Body of Christ. Here, too, is a possible context for reflecting and considering how the Traditional Latin Mass fits—or does not fit—the synodal church’s life of worship.

Making these distinctions and entering these sensitive conversations are clearly not matters of bickering over marginal issues in our life of faith. The Eucharist belongs at the very center of who we are and what ought to claim our full attention as we strive to celebrate it and receive it with all authenticity. This became clear to me as I did my doctoral work on the service tradition in the Gospels.

In the Gospel of Mark, we find a phrase at the heart of Jesus’ mission of service: “For the son of man came not to be served but to serve and give his life as a ransom for the many” (10:45). This verse also ultimately expresses the kind of service to which we, whether we live out the priesthood of the baptized or of the ordained ministry, are all called. The essence of Jesus’ service, as described in this verse, is not tied to functions. It is simply and uniquely the gift of his life for others: “to serve and give his life.”

We serve not primarily through the various functions we exercise but through the gift of ourselves. In the Eucharist, we discover the abiding pattern and enabling of that self-sacrificial love for the whole of our lives. And we do this not just by ourselves or for ourselves. We do this through, with and for the entire priestly people of God, so that, with Paul, we urge one another: “Brothers and sisters, by the mercies of God, present your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to God, which is your spiritual worship” (Rom 12:1). In this way, we become what we celebrate in the Eucharist.

The Eucharistic landscape is indeed complex, but the Eucharist itself remains the simple and abiding center of who we are, what we do and where we hope to go.