When the pilot of Bockscar unleashed a five-ton plutonium bomb on Nagasaki’s Urakami Valley, then the home of some 12,000 Christians, on the cloudy morning of Aug. 9, 1945, a blast of heat and wind engulfed a one-mile radius and consumed in a flash tens of thousands of people. Smoke over Kokura, the Americans’ initial target, had obscured the city below, so the crew had pivoted toward Nagasaki. The bomb, known as Fat Man, wrought damage across 43 square miles of land and sea, an area roughly the size of Disney World.

The bomb’s detonation was so final, so utterly absolute, that estimates of its human cost are impossible to confirm. Perhaps 70,000 people ultimately died in the blaze. Or maybe it was 140,000. They say that approximately two-thirds of the city’s Catholic population disappeared when American airmen opened the gates of hell 80 years ago.

But we are certain the cathedral was destroyed because Father George Zabelka saw its ruins. And what he saw in the medical centers of Hiroshima and Nagasaki a few months after the bombings—the charred bodies of children, the keloid scars of the elderly, the vacant holes in the skulls of victims where their eyeballs once sat—would haunt him for decades until this military veteran made a surprising and public conversion to nonviolence.

Eight decades after the end of World War II, why should Catholics today care about a military pastor who changed his mind on the bomb? He exists now as a symbol of conscience, a symbol who can communicate the message of Gospel nonviolence, says Emmanuel Charles McCarthy, a Melkite Catholic priest who helped guide Father Zabelka toward a rejection of war. The late priest remains an “incarnation of conversion,” wrote Father McCarthy, “a textbook case of the mystery of ‘truth, freedom and grace’ overcoming falsehood, fear and normalized evil.”

‘I Wanted to Get Into Action’

The son of a former Austrian soldier, Father Zabelka was born in Michigan in the spring of 1915; he spent the 1930s riding the tracks and looking for work, according to Father McCarthy. (He remarked, in a 1992 obituary, that Father Zabelka played guitar “with a hillbilly band” during his college years.) By 1941, several months before the attack on Pearl Harbor, Father Zabelka had been ordained a parish priest in Flint, and he attended chaplaincy school at Harvard University before joining the military in 1943 and training as a paratrooper. After stints at Fort Jackson in South Carolina and Wright Field (now part of the Wright-Patterson Air Force Base) in Ohio, Father Zabelka arrived on the Pacific island of Tinian, part of the Northern Mariana Islands, in the summer of 1945. “I wanted to get involved in the war. I wanted to get into action, because that’s where people really needed chaplains,” he said in 1988.

On that remote island 1,500 miles south of Tokyo, the hawkish “General George,” his tongue-in-cheek sobriquet among soldiers, served as a chaplain to the 509th Composite Group, an Army Air Forces unit preparing for some secret project in the near future. Something about a bomb, they heard. In time, their mission was revealed: Strong-arm Japan into an unconditional surrender through the “prompt and utter destruction” of its cities and people.

“The thought of civilians being obliterated by bombing just didn’t seem to enter our mind,” explained Father Zabelka. That Nagasaki maintained a rich history as a Catholic city did not bother him either. It was a target. He blessed the men and they did their jobs. It would be some months until he understood how his men had scarred the landscape of those far-away cities.

The bomb exploded not far from the former Urakami Cathedral, whose construction began in the late 19th century after Japan’s “hidden Christians” returned from various detention camps. A nuclear weapon had reduced what was once the largest church in East Asia (230 feet long with two 100-foot bell towers) to a bombed-out husk. In 1958, its hollow structure was demolished, to much controversy, and the church was rebuilt. “A ruined Catholic cathedral provided one of the most recognisable reminders of atomic devastation” for Urakami District residents, wrote the historian Gwyn McClelland in 2023.

Father Zabelka visited the cathedral site in the months after the bombings and spotted a piece of a broken censer, used to burn incense, amid the debris. In an interview in August 1980, a few years after he began his new life as a peace activist, the priest said that when he looked at the censer he prayed that “God forgives us for how we have distorted Christ’s teaching and destroyed his world.”

By the mid-1950s, Father Zabelka was assigned to the former Sacred Heart Catholic Church in Flint, Mich. Back in his home state, he hoped to forget the war and focus on his pastoral duties. He became devoted to civil rights and was described by a Flint-area social worker as “the only white [man] who was able to walk the street alone” while Detroit succumbed to riots in 1967. Profoundly moved by the nonviolent philosophy of Martin Luther King Jr., Father Zabelka joined the Baptist minister on the 1965 march in Selma, according to a posthumous remembrance of the priest.

“Martin Luther King brought me into the notion of nonviolence for the first time,” said Father Zabelka in a 1988 documentary. “Before that, the violent way was the only way.” Since the war, Father Zabelka said, a kind of worm had “squirmed through [his] stomach,” giving him conscience pangs about his involvement in the bombings and sickness he witnessed in Japan. Still he struggled with the nonviolent message of Christ in the Gospels, specifically the instruction to love one’s enemies: “You have heard that it was said, ‘Love your neighbors and hate your enemy.’ But I tell you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, that you may be children of your Father in heaven” (Mt. 5:43-45).

‘A Conversion to Nonviolence’

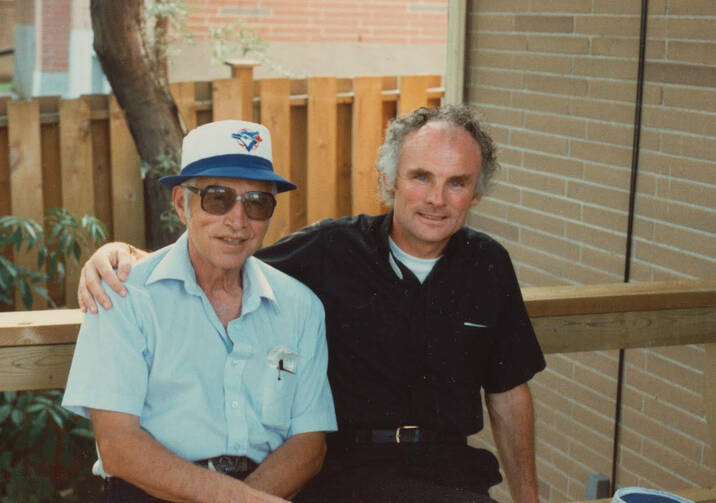

In 1973, Father Zabelka attended a retreat on nonviolence in Brighton, Mich., for priests of the Diocese of Lansing. Directed by the 33-year-old Emmanuel Charles McCarthy, a former instructor at the University of Notre Dame who held a law degree from Boston College, the retreat began inauspiciously. In an interview with America, the Boston-born Father McCarthy, ordained a Melkite Catholic priest in 1981, said that only eight diocesan priests attended the retreat. He recalled his first interaction with Father Zabelka.

“He was obnoxious. Absolutely obnoxious,” said Father McCarthy. The former military chaplain arrived at the retreat belligerent and ready to debate. He interrupted the talk repeatedly with comments and questions. “What about all those children destroyed at Auschwitz?” Father Zabelka reportedly asked as he pounded his fist on the table. It would be several years before the retreat leader would learn the background of his antagonist. “The whole [retreat was] a flop. A flop,” said Father McCarthy. “I was glad to get out of there.”

It was a surprise when, about six months later, McCarthy was invited by Father Zabelka to give a retreat at St. James Catholic Church—now the Catholic Community of Saints James, Cornelius and Cyprian—in Mason, Mich. (He had been assigned there in the early 1970s.) At the rectory, McCarthy noticed that the pastor had purchased the nonviolence-themed books mentioned at the previous retreat. This time, Father Zabelka sat in the back of the crowded church and listened quietly until the end of the talk. Father McCarthy said the ex-chaplain then asked a memorable question: “Do you mean to tell me that Jesus wouldn’t enjoy a good boxing match?” (The answer was that he would not.)

Father Zabelka shocked his friends and parishioners in the mid-1970s when he revealed, in his annual Christmas letter, that he had rejected the violence of his past and become firmly convinced that nonviolence was the way of Christ. “This was not a conversion to an anti-nuclear stance. This was a conversion to nonviolence,” said Father McCarthy in 2020. Father McCarthy had difficulty interesting publishers in a book on Father Zabelka, so the two decided on an interview instead. Published by Sojourners in August 1980, the interview, in which the former chaplain described being “brainwashed” by the military into believing the nuclear bombings were necessary, proved influential to readers.

When Auxiliary Bishop P. Francis Murphy of Baltimore sought to develop “a concise statement” from the National Conference of Catholic Bishops on the ethics of war, “the major influence on Murphy may have been Father George Zabelka,” writes the journalist Jim Castelli in his 1983 book The Bishops and the Bomb. (Castelli notes that Bishop Murphy had read the Sojourners interview.) The bishop’s initial efforts would culminate in the 1983 publication of “The Challenge of Peace,” a major Cold War-era pastoral letter that summarized Catholic teaching on just war and nonviolence.

‘When the Heart Attacks Came’

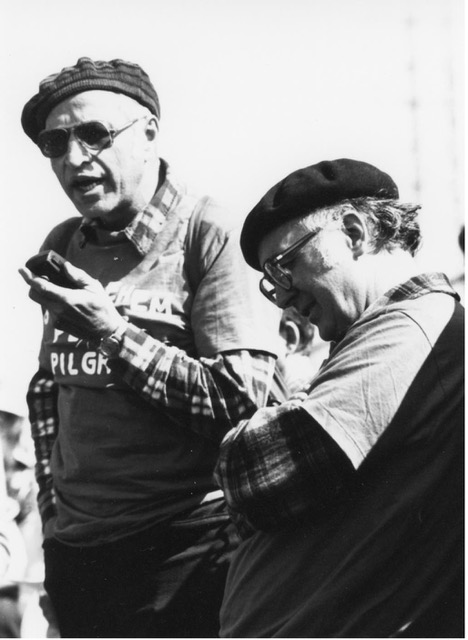

The Sojourners interview directly inspired Jack Morris, S.J., who co-founded the Jesuit Volunteer Corps, to launch a 6,700-mile peace walk in early 1982 from Bangor, Wash., across the United States and Europe, and ending in Bethlehem in Palestine. James Patrick Thomas, a nuclear disarmament activist who joined Father Zabelka on the Bethlehem Peace Pilgrimage, which concluded in December 1983, first learned of him by reading the 1980 interview. Thomas encountered Father Zabelka, the oldest of 20 pilgrims, as someone intensely private and “standoffish.”

“It was a challenge for George all along, the whole trip, to enter into a community. He was a retired diocesan priest from Michigan, and being in community was an entirely new experience for him,” said Thomas in an interview with America in July.

By the fall of 1983, Thomas began to worry about the health of Father Zabelka, who had already suffered two heart attacks before the march. (“Along comes Vietnam. The mad bombings. I’m recalling Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” he told the historian Studs Terkel in 1983. “That’s when the heart attacks came.”) In his memoir Atomic Pilgrim, Thomas writes that he watched the aging priest, exhausted by the arduous journey on foot across the United States and Europe, pop nitroglycerin pills and feared he would die before they reached Athens. When the group arrived outside of Bethlehem at the end of 1983, Father Zabelka fainted during the closing prayer service.

Thomas described the unlikely peace activist, walking with “Hiroshima” scrawled on the back of one shoe and “Nagasaki” on the other, as entirely devoted to the elimination of the nuclear threat and intensely focused on Christ’s command to love your enemies. “That became kind of a mantra for George in his public speaking. Love your enemies. He just kept trying to drive that home to people,” said Thomas.

In his later years, Father Zabelka remained active delivering talks to peace groups and driving around in his lemon of a car, plastered with stickers like “If You’ve Seen One Nuclear War, You’ve Seen ’Em All!” He returned to Japan for the first time since the war in July 1984 to participate in another peace march and apologize to survivors, calling his trip to a renewed Hiroshima “a pilgrimage” to “expose the lie of a ‘Christian’ war.” In 1986, he told Terkel, who once described the elderly Father Zabelka as “a cross between a leprechaun and bantam prophet,” that international religious leaders should convene an ecumenical council to affirm that killing is a sin. “If all the world religions would join in and make this clear statement, it would have a terrific impact,” he said six years before his death in 1992.

‘A Dangerous Catastrophe’

Among servicemen connected to the bombings, Father Zabelka was not the only one who later had moral misgivings. Richard Sherwood, known as Dick, a 21-year-old Air Force pilot who took reconnaissance photos of the devastation in Hiroshima shortly after the bombing, was horrified by what he witnessed and dedicated his life to preventing an “atomic holocaust.” Claude Eatherly, a Texan who flew Straight Flushto assess weather conditions above Hiroshima, said he was tortured by guilt following the war, becoming a small-time criminal well-known in the psychiatric ward of his local veterans’ hospital. However, the investigative journalist William Bradford Huie questioned accounts of Eatherly’s professed guilt and suggested he had been motivated by a desire for fame.

Father Zabelka was certainly at odds with the Rev. William “Bill” Downey, the Protestant chaplain to the bombing crew who strongly supported the military action and repeatedly insulted his Catholic counterpart in interviews. “People are going to think that’s me. It’s not,” said Rev. Downey in reference to Father Zabelka. “I’m glad they dropped [the bomb]. It saved a lot of lives.”

Eighty-five percent of Americans approved of the bombings in August 1945, according to a Gallup poll. Catholics were split on the topic. Religious leaders of various faiths presided over victory ceremonies to celebrate the war’s end. Grateful Catholics gathered at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City after President Harry S. Truman announced Japan’s surrender, and 4,000 congregants attended “a solemn mass of thanksgiving” in New York 10 days after the bombing of Nagasaki. At St. Patrick’s, Father Thomas F. Maher said that “America had [led] the Allies to victory” and called on the nation to pursue peace, according to The New York Times.

Other Catholics opposed the development of nuclear weapons. In a 1943 address to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, Pope Pius XII warned that the awesome power of the atom could be harnessed to provoke “a dangerous catastrophe,” and five years later he decried the bomb as “the most terrible arm which the human mind has thus far conceived.” Fulton J. Sheen, in 1946 a popular radio presenter and professor at the Catholic University of America, criticized the bombings for killing civilians, while Dorothy Day offered a scathing condemnation of American force in The Catholic Worker.

It took Father Zabelka three decades before he agreed with Dorothy Day, before he encouraged strangers on the street to “do something for peace.” And according to Father McCarthy, the surprising life of this paratrooper turned pacifist was “God-designed,” offering “a most persuasive communique to the church” that followers of Christ must turn against violence and have the strength “to see the obvious in the Gospel.”