A Homily for the Fifth Sunday of Easter

Readings: Acts 14:21-27 Revelation 21:1-5a John 13:31-33a, 34-35

That the spirit of revolutionary change, which has long been disturbing the nations of the world, should have passed beyond the sphere of politics and made its influence felt in the cognate sphere of practical economics is not surprising. The elements of the conflict now raging are unmistakable, in the vast expansion of industrial pursuits and the marvelous discoveries of science; in the changed relations between masters and workmen; in the enormous fortunes of some few individuals, and the utter poverty of the masses; the increased self-reliance and closer mutual combination of the working classes; as also, finally, in the prevailing moral degeneracy.

Those are the opening lines of a papal encyclical, though not from our new Holy Father. He did not take the chair of Peter with a set of prepared pronouncements.

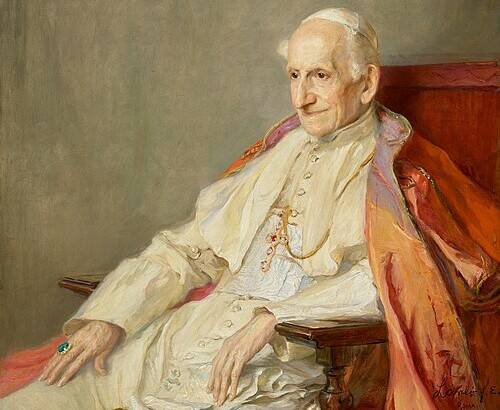

As contemporary as they sound, these lines come from his 19th-century predecessor, Pope Leo XIII. The encyclical was entitled “Rerum Novarum,” after its opening words, which my prosaic Latin renders as “new things.”

Several translations of the encyclical into modern European languages are offered on the Vatican’s website. They all translate those two Latin words, rerum novarum, quite freely: The Italian version speaks of “the ardent longing for novelty” (L’ardente brama di novità); the Spanish, of an awakened revolutionary itch (Despertado el prurito revolucionario); and the French, of the thirst for innovations (La soif d’innovations).

“Rerum Novarum” was issued in 1891 at the height of the Industrial Revolution. It has become one of the most famous papal encyclicals, serving as the foundational document for the social teaching of the Catholic Church. All subsequent popes have cited it.

In the face of rising socialism, one form of which would become communism, Leo XIII’s encyclical vigorously defended the right to private property, warning with prescience that its abolition would lead to state control of even the most private elements of life.

At the same time, the pope rejected unfettered capitalism, observing that “the hiring of labor and the conduct of trade are concentrated in the hands of comparatively few; so that a small number of very rich men have been able to lay upon the teeming masses of the laboring poor a yoke little better than that of slavery itself” (No. 3). As proof of that, Leo observed a consequence still quite contemporary: “For no one would exchange his country for a foreign land if his own afforded him the means of living a decent and happy life” (No. 47).

Leo insisted upon the rights of workers, including their right to organize (No. 49). Most importantly, Leo warned that rapid economic changes posed grave dangers to human dignity, even human flourishing. At the close of the 19th century, this patrician, Italian pope essentially predicted the 20th century and a good portion of our 21st century.

It has been said that the first message a new pope sends to the world arrives even before he steps onto the loggia of St. Peter’s Basilica. It comes in the choice of his name, which is communicated to the world before the new Holy Father appears.

Had Cardinal Robert Prevost chosen to be called “Francis II,” he would have foreclosed speculation about the future of the church. To a lesser degree, the same is true for the names “John,” “Paul” or “John Paul.”

The name a new pope chooses already speaks both to his vision of the future and how he sees himself being grafted into the church’s history. The previous Pope Leo warned us that human ingenuity and the powers that come from it were outstripping human wisdom and compassion.

Perhaps just as telling is the legacy of the first Pope Leo, the man whom we now call Pope St. Leo the Great. He came to the chair of Peter in a “Mad Max” moment, at the dawn of what would later be called the Dark Ages. The Roman Empire was collapsing in the West. Before he turned back a marauding Attila the Hun, Pope Leo had first to repair Rome’s plumbing and extinguish the fires that were gutting the city’s ghettos.

Rerum novarum. New things: new challenges, new threats, new opportunities. Is taking the name Leo XIV a way of saying to Christians and non-Christians alike that it is later than we think? Are environmental and economic changes gaining not only unstoppable but also uncontrollable momentum? Should we call it “artificial intelligence” if it is not marked by even a modicum of human wisdom? Rerum novarum. New things.

The One who sat on the throne said,

“Behold, I make all things new” (Rev 21:5).

Here is the heart of the Christian faith, a characteristic that distinguishes it from so many other forms of religious life. The risen, glorified Christ does not make “all new things.” No! He makes “all things new.”

The life yet to come will not cancel what came before. Risen life redeems, rather than erases, what now exists. Salvation plays out in history, not apart from it. Our triumphs, individual and collective, always matter because they lay the foundations of what is yet to come. Christ will come in glory to validate our visions, our ardent longings, our revolutionary itches, our thirst for innovation.

Christ does not even cancel our failures! No, he redeems them in a way we can only imagine when we ponder the wounds, which the crucified one still bears in eternity.

Most importantly, Christ comes to claim the best of us. He returned from the tomb to re-establish relationships, to reclaim the loves that he had enkindled on earth.

Rerum novarum. New things. Grave new threats on the horizon but also the dawn of tremendous graces. Small wonder, then, that after shocking us in the choice of his name, the new pontiff immediately reschooled us in the message of Easter.

Peace be with you! Dearest brothers and sisters, this was the first greeting of the risen Christ, the good shepherd who gave his life for the flock of God. I, too, would like this greeting of peace to enter your hearts, to reach your families and all people, wherever they are; and all the peoples, and all the earth: Peace be with you.

God loves us, all of us, evil will not prevail. We are all in the hands of God. Without fear, united, hand in hand with God and among ourselves, we will go forward.

Rerum novarum. New things. The world will always be tempted by mere novelties because it seeks something it still has not found. As St. Augustine put it so long ago, “Thou hast formed us for Thyself, and our hearts are restless till they find rest in Thee” (Confessions, I.1).

In his first address to us, the Augustinian Pope Leo XIV reminded us that what we need, who we need, is the one who makes all things new.

We are disciples of Christ, Christ goes before us, and the world needs his light.