When a character gives a speech in a play—whether it is a soul-searching soliloquy, a public testimony or a bona fide bit of chest-thumping oratory—it functions somewhat like a song in a musical. It takes us out of the realm of ordinary dialogue, to a place either inside a person’s deepest thoughts or hovering somewhere slightly above the action, commenting on it. But when a play’s subject is politics, the lines between the private and public spheres blur, and speechifying is not just a rhetorical register the play can sample but part and parcel of the everyday language and behavior of the human beings at hand.

So when the playwright Robert Schenkkan shows the characters in his new play All the Way giving speeches, he is both examining their arguments and simply portraying them in their natural habitat. In staging the whirlwind 11 months that began Lyndon Baines Johnson’s fateful presidency, Schenkkan has activists, congressmen and above all Johnson himself regularly address us as their audience, effectively casting Broadway theatergoers alternately as members of Congress, convention delegates, mourners and, more broadly, as the jury of historical hindsight, weighing the compromises and political horse-trading that led to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the fraught, divisive aftermath whose fault lines still undergird much of our political discourse.

But the dangerous temptation of writing a play about habitual speechgivers, which Schenkkan does not always escape, is that the whole thing can feel like an oral argument geared toward a preordained verdict. When, late in the play, a campaign speech by Johnson (Bryan Cranston) is artfully juxtaposed with the Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech by Martin Luther King Jr. (Brandon J. Dirden), and capped by piped-in applause that tells us they have won the day fighting the good fight, the valorizing glow, however well-earned, seems a bit much. On the other hand, there is the startling moment when David Dennis, a leader with the Congress of Racial Equality, interrupts King’s eulogy for slain activist James Chaney with a fierce, impassioned jeremiad calling for righteous anger to be channeled into direct action. As delivered by Eric Lenox Abrams from a balcony, then from the house of the Neil Simon Theatre, it is a theatrical gambit that breaks the play’s procedural rhythms, to bracing effect.

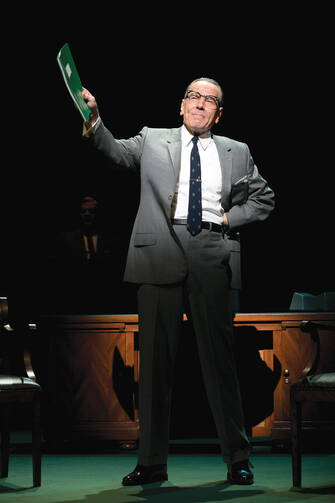

Even when Schenkkan’s characters are not giving speeches, they are on the historical record, as director Bill Rauch’s often stirring, sinewy staging makes clear: Cast members are arrayed behind banks of paneled desks, in a quasi-congressional chamber, to silently observe even the most intimate scenes of backroom cajoling and strategizing. While this sense of shared attention gives the play a strong and supple ensemble feeling, it is in the scenes of Johnson’s wheeling and dealing, in which he alternates drawling flattery with baldly gangsterish threats to achieve his aims, that the play eventually comes into focus, and into its own. For if Schenkkan has not quite written the world-beating historical drama he seems to have wanted to, he has without question written a bang-up acting vehicle for a star of Cranston’s outsized talents.

This may sound like faint praise, but to write a solid Great Man of History play, particularly in an age when our trust in institutional leaders has reached a historical nadir, is no small thing, not least because Schenkkan is implicitly nodding to Shakespeare’s monarchical history plays; “All the Way” was commissioned by the company Rauch runs, the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, as one in a series of plays about American history. (Schenkkan’s sequel, “The Great Society,” opens in Oregon this coming summer.) And Cranston, though craggier and leaner than L.B.J. ever was, has an unmistakably presidential presence that is evocative not only of Johnson but of a veritable sampler of 20th-century presidents: His fine, thin-lipped patrician profile occasionally suggests George H. W. Bush, while his strategic deployment of good-ol’-boy bonhomie has a faintly Clintonian lilt. There is even a touch of Nixon in the way his paranoia and wounded pride lead him to some distinctly bad decisions, some of them in concert with the oleaginous J. Edgar Hoover (Michael McKean). Cranston also achieves the remarkable feat of suggesting Johnson’s growing weariness and shaky health while at the same time powering a three-hour play in which he very seldom leaves the stage.

And to be clear, the role of L.B.J., historically as well as theatrically, is more than just a bravura acting challenge. Johnson’s presidency was one of the great pivot points in American history, with his stance on civil rights going hard against the grain of his Southern Democratic roots and effectively realigning the country’s two major parties. The Civil Rights Act was both an unquestionable progressive victory and a setback to the larger progressive project, severing the New Deal coalition of Northern and Southern Democrats and sparking a backlash that would lead the country resolutely rightward in the last decades of the century. Even today the borders of the old Confederacy, though flipped to the Republican column after a century of Democratic control, remain a startlingly reliable guide to voting patterns.

Schenkkan deftly teases out these strains, with Dixiecrat George Wallace (Rob Campbell) presciently invoking Southern-ness as a philosophy that transcends the region to encompass all those who want the federal government to “leave me the hell alone,” and Johnson hitting back at constitutional objections to civil rights laws as simply the last refuge of “those who got more, wantin’ to hang on to what they got, at the expense of those who got nothin’.” The resonance with today’s battles over health care, entitlements and voting rights are neither unintentional nor unwelcome.

In dramatizing the often arcane legislative maneuvers for which Johnson had a special, Senate-honed genius, “All the Way” feels very much of our time. In the age of the 24-hour news cycle, not to mention such fine-grained political narratives as the film “Lincoln” and the series “House of Cards,” audiences are more primed than ever for the suspense of deal-cutting and vote-counting, of discharge petitions and House rule-breaking. Schenkkan does a credible if rather rote version of this brand of wonk drama in the play’s first act, but it is in the play’s second act—detailing the bloody Freedom Summer in Mississippi and the not-quite-integrated Democratic convention of 1964, not to mention the escalation of American involvement in Vietnam—that the tragic dimensions of President Johnson’s character and, by extension, America’s begin to swell into view. Rauch’s staging becomes accordingly rangier, rawer and less reducible to mere argumentation. As “All the Way” finally reminds us, the stakes of this still ongoing struggle may be stratospherically high, but the tools to wage it are not so out of reach.