In rugged mountains east of Seoul, Korea, in forests marked by wild streams, the footpaths of hardy hikers and the rooting spots of wild boar, Nature and Star Lodge nestles at the end of a road up a steep valley.

At a weekend retreat I led there, under images of galaxies and stars projected on a high ceiling, the retreatants and I paused to feel Earth’s gravity pull us into our seats with a sense of awe arising as we found ourselves in the midst of the miraculous universe. The participants included a priest, a nun and Koreans with Italian Christian names like Angelo and Maria, a custom in Korean churches. Mr. Kim, the founder and owner of Nature and Star Lodge, was also among us. He is a quiet, intuitive man sought out for counsel by friends and parishioners.

It was early December, so I included Christmas carols in the retreat program to encourage expression from throats and diaphragms as well as hearts and minds. Often a familiar practice or text, like a carol, offers a gateway to deeper feelings and perceptions.

The retreat was going well, but the people still seemed in a more intellectual frame of mind, perhaps because following my English and elementary Korean and then listening to a professional translator was primarily an intellectual exercise.

Nearing the end of our time together one day, as people shared with each other in pairs, I prayed quietly that we could deepen the experience and that participants would find a practice of prayer that would make a difference to them after the retreat. An idea came to me, reminiscent of a practice I encountered in a Jesuit retreat: to work with the most familiar practice of all. Calling the room back to order I invited them to share highlights of the previous exercise and then asked, “Who here has said the Our Father at least 1,000 times?”

The nun looked around the room and then back at me as if I had asked a foolish question, “Everyone,” she said.

“Ten thousand times?” I asked.

They looked around at one another, all nodding, “Yes, everyone.”

“One hundred thousand times?”

“Most, yes maybe all of us.”

I looked slowly at each face then asked, “Did you pray like this? Our father, who art in heaven, I have got to start supper before the kids get home, Hallowed be thy name, I hope I get this sales contract, Thy kingdom come, I wonder what time it is….”

They first looked surprised, then nudged one another, smiling in recognition.

“Do you think Jesus had something in mind when he gave us that particular prayer?” I asked. “Perhaps he is encouraging us to turn our attention in a different direction to realize something we did not previously notice. Perhaps Jesus gave us a key. But do we ever pause to wonder what that key is designed to open? Are we focused on the key or on the door?”

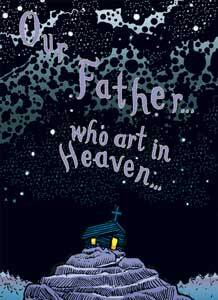

As interest sparked, I invited them to put themselves into a prayerful state and, when someone felt ready, to say slowly the first line of the Our Father in Korean. I suggested they listen to the phrase and rest in contemplation. Why would Christ ask us to say those words? After a few moments, when another person felt moved to speak, they should slowly say the next line of the prayer. Again we would remain silent for three breaths and consider the phrase.

As they entered silence and the priest said the first line, I began to pray an Our Father silently in English. The pauses they left between the lines were longer than I expected; the phrases of the familiar prayer were spoken in earnest and with focused attention. When the prayer was over, the intellectual frame had given way to a feeling of well-being and deep connection. We sat quietly for a few minutes reflecting on what had happened and then took a short break. The workshop closed at the appointed time an hour later.

A few days later, Mr. Kim told a participant that after the retreat, in a building he had erected with his own hands but in which for years he had a sense of the “energy not being right,” something had shifted. He had a peaceful feeling there for the first time.

Since that weekend I have often prayed with silent pauses between the lines, and I am still startled by what sometimes happens during one heartfelt Our Father. What each of us finds there differs of course. For me, in the first two words I sometimes hear myself calling out, almost imploring the Lord to be present. Then I realize it is I who am less than fully present. Sometimes the spaces are filled with racing thoughts on unresolved issues. At those times I leave space for a few more slow breaths until the storm settles, until I realize that my prayers are answered by grace and blessings. When I forgive others, I feel a release of the judgments and unhappiness that were hurting me more than anyone else. I don’t wish to bring unhappiness to anyone, I realize; if they were happy and aware they would rarely offend others. So I begin to pray for them, too.

More than a year later, while at a Christian service at an interfaith gathering on the National Mall next to the Washington Monument, I invited many participants from diverse traditions to pray one Our Father in that way. The spaces between the lines grew as peace moved through the crowd. Later that morning, a pair of eagles circled above the gathering followed by a rainbow around the sun in an otherwise clear sky. Silence between the lines can smile upon us in many ways.

Yes, it was a revelation to see, that, in reading between the lines of just three words, "Our Father Who..." that the "I Am Who I am" of Siani, was really Father, best understood through the word "Our," revealing the Unknowable One as Universal Father, pulling together the brotherhood/sisterhood of all humanity. This understanding suddenly focused on St. Paul's endearing designation of the "I Am Who I Am" as "Abba" which brought to mind something that Auxiliary Bishop of New York Patrick V. Ahearn said in a Confirmation homily.

Once, while visiting the Holy Land, the Bishop recalled the scene of a small child running, then scraping his knee as he fell and immediately running to his Father nearby crying out, "Abba! Abba! Abba!" Bishop Ahearn asked the child's Father to explain what the child was saying and the Father replied, "In English he would be craying out, "Daddy! Daddy! Daddy!" Wow!

So, then, St. Paul would have us relate to the "I Am Who I Am" to the Unknowable One, as "Daddy!" God, that's wonderful! And all this from reading between the lines of just three words of the "Our Father!" Thanks Mr. Berry for your stirring essay. Your insight has taught me better what Jesus meant when he said, "When you pray, say, Our Father (Who?) ...!"