On the morning of Nov. 8, before the sun rose over the nation’s capital, illuminating the somber black granite of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, a name was read aloud.

It is one name of over 58,000 spoken during the Reading of the Names ceremony, which takes place every five years. According to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, thousands of volunteers and veterans came to Washington, D.C., from Nov. 7 to Nov. 11 for this year’s event, celebrating the 40th anniversary of the memorial.

This name sits on line 43 of panel 12E of the wall. It is the name of an Army veteran, one who died on another Nov. 8, 56 years ago. It is the name of a chaplain, one of only 16 men of God whose gray names relieve black stone of the memorial.

It is the name of the Rev. Michael Quealy, the first military chaplain killed in action in Vietnam. On the morning of Nov. 8, 1966, he jumped into a medical evacuation helicopter with a unit that was not his own, according to a contemporary article from The Associated Press. When an officer tried to stop him, he reportedly said, “My place is with them.” Hours later, he was dead.

“He was a good example of what a priest should be and what a person should be.”

His life story is not especially well known, but those who knew him said that he modeled a profound humility and devotion to service that stayed with him until the moment he died.

“There was no pretense about him,” his second cousin, Sharon Parks Loftus, said. “He was a good example of what a priest should be and what a person should be.”

Michael Quealy was born on Sept. 11, 1929, to Irish immigrants Michael and Margaret Quealy. He had two younger sisters and an older sister, and their father was a baker who never attended high school. He grew up in West Harlem in New York, in an ethnically diverse neighborhood where the biggest similarity among families was their modest financial means.

Father Quealy’s upbringing had an enormous impact on his path to the priesthood, according to Ms. Loftus. Her and Father Quealy’s parents were cousins, and Ms. Loftus remembers occasionally seeing Father Quealy during her childhood in Newark, N.J. She said that he always wanted to be a missionary and help however he could in other parts of the world.

Father Quealy: “My place is with them.”

This vocation led him to the Maryknoll Fathers and Brothers, who educated Father Quealy from age 17 to 26 at schools in Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Illinois. After a year as a novice in Bedford, N.Y., Father Quealy moved to Maryknoll Seminary in Ossining, N.Y., in 1954.

The cost of attending seminary, however, sent Father Quealy in an unexpected direction not long after he finished. Ms. Loftus said that Father Quealy struggled to pay for his education and made an agreement with a bishop from Alabama. Father Quealy would receive funding in exchange for several years of service as a diocesan priest in the then-Diocese of Mobile-Birmingham.

Ms. Loftus recalled that those were hard years for Father Quealy. He was deeply troubled by segregation in Alabama during the late 1950s and early 1960s. The Associated Press reported that Father Quealy served four churches for white people only and one for Black Catholics. The experience, Ms. Loftus said, left Father Quealy feeling very far from Harlem.

“Father Mike wasn’t a man of a lot of words. He was very quiet but always gave you the time of day and his full attention when you wanted to talk to him.”

After six years serving in Alabama, Father Quealy’s missionary spirit led him to make a drastic decision: to join the Army’s Chaplain Corps and ship out to Vietnam. He attended Army Chaplain School at Fort Hamilton in Brooklyn, N.Y., before being stationed at Fort Ord in California.

Self-proclaimed “army brat” Steven Watts remembers moving to Fort Ord with his family and altar serving at Father Quealy’s Masses. He said that the soft-spoken Irishman used to practice his Sunday sermons to an empty chapel on Saturday.

“Father Mike wasn’t a man of a lot of words. He was very quiet but always gave you the time of day and his full attention when you wanted to talk to him. I mean, it was like you were the only person in the world Father Mike was there,” Mr. Watts said.

California was Father Quealy’s final stop in the United States before he deployed and joined the First Infantry Division’s Third Brigade. It was June of 1966, a little over five months before he would be killed.

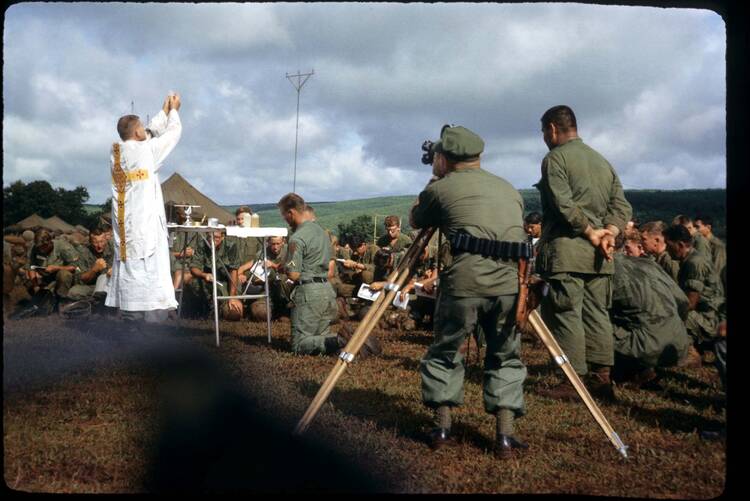

In those five months, Father Quealy made a habit of hopping onto whatever evacuation helicopters happened to be revving up.

Reports generally agree that Father Quealy ran to the most besieged part of the battlefield and began assisting with medical evacuations.

A press release from the information office of the First Infantry Division states that “he had seen battle in Operation El Paso, Operation Shenandoah, and, finally, in Operation Attleboro. For him, the battle of November 8 differed only in the way it ended.”

On that day, reports generally agree that Father Quealy ran to the most besieged part of the battlefield and began assisting with medical evacuations. By one sergeant’s report, “at least five of those guys owe[d] their lives to him.” Father Quealy was hit with machine gun fire and died in the field. He was posthumously awarded a Purple Heart.

Father Quealy was neither the last chaplain to die in action in Vietnam nor the most highly decorated. In fact, a New York-born priest who also attended Maryknoll just a few years after Father Quealy would earn the Medal of Honor after dying among Marines in Vietnam. The Rev. Vincent Capodanno, known as “the Grunt Padre,” is a recognized Servant of God and has a devoted cause for canonization.

Almost 3,000 chaplains from every branch of the military served in Vietnam, each with vastly different experiences but a common commitment to minister where they were needed. Sixteen of their names were read aloud this week in Washington D.C.; priests, ministers and rabbis; immigrants and men of color; soldiers who died giving spiritual comfort to the wounded or dying. Each has a story of bravery and faith as remarkable as Father Quealy’s.

Father Quealy was laid to rest in Old St. Raymond’s Cemetery in the Bronx. According to Mark W. Johnson, a historian with the U.S. Army Chaplain Corps, a pilot and friend of Father Quealy’s personally retrieved his body and the items that were with him when he died.

Among his effects was his diary, the last entry of which was a quote from the Gospel of St. Matthew: “So will my heavenly Father treat you unless each of you forgives his brother with all your heart.”