Two of the happiest years of my life were spent as a stay-at-home dad when our son, Isaiah, was a toddler. The morning of Sept. 11, 2001, began like most of our days with a meandering walk around our neighborhood after breakfast, stopping whenever we met something of interest: a slug wending its silvery path across the sidewalk; a handful of pebbles to throw, one by one, into the street; a neighbor planting flowers along her driveway. An hour later, after a troubling phone call from my wife about the events unfolding in Manhattan, I was fixed to the television while trying to keep Isaiah occupied in another room. I could not fathom the scene before my eyes—much less could I allow the images to burn their way into a child’s imagination.

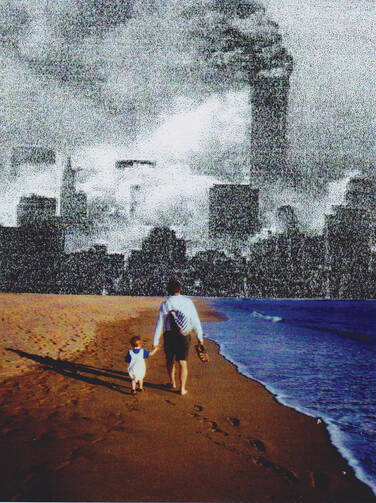

Some months later, in a reverie of prayer and artistic experimentation, I created an image by cutting and pasting vacation photos and news stories from Sept. 11, 2001. It is hard to express what I feel today, 15 years later, when I contemplate this image, with its apocalyptic juxtaposition of father and son walking on the beach against the smoldering buildings and silent cry of Manhattan in the background. There’s at least this: The same painful vulnerability and almost desperate love of a parent, who hopes against hopelessness for something better than what appears to lie on the horizon for my children—for all the world’s children—as the world’s grownups study and prepare and continue to practice the terrible art of war and revenge.

Yet it is in our acts of mercy, not retribution, that we share in the very life of God. Then there is no separation. When we live in the spirit of mercy, we become God’s hands and feet in the world. Measuring the whole human situation, Jesus reorders all relationships under the demanding light of God’s care for all persons, guilty and innocent alike. Jesus, the wisdom of God incarnate, sees and responds to all things in the light of God’s scandalously inclusive love. To live “in Christ” is to strain every muscle to do likewise. Blessed are the peacemakers, no matter their creed, for they are daughters and sons of God.

“A world without mercy is not a human world,” Cardinal Walter Kasper has written. And a world without merciful human beings, religions, cultures and societies is a world without God. God needs human beings to be God’s redeeming action in the world. Jesus’ command to love our enemies presumes our graced capacity to do so. Is Christ’s trust in us misplaced? Our image of humanity—of ourselves, our religion, our nation—is inseparable from our images and narratives of God.

To practice the presence of God in the world is to be and become what we receive freely, with every breath: the divine mercy. Yet our drones fill the skies in the East and strike with fury from above. The wheel of retribution spins round, a juggernaut rotating between us and them, generation after generation. Where is God? With whom is God? Is God? Jesus measures the situation, bends down, runs his fingers through the earth and asks the pivotal question. He is asking still.

In his sublime prose poem “Hagia Sophia,” Thomas Merton narrates one man’s awakening to the “soft voice” of Wisdom, the God whose loving presence shines from within all things “like the air receiving the sunlight.” She is God’s relational essence, the dance of love itself in the heart of the Trinity, poured out from the dawn of time, unleashing the inner dynamism and “suchness” of all created things, even the most humble. She is the child who “is prisoner in all the people, and who says nothing.” Above all she is God’s mercy—or mercying (misercordiando), to borrow Pope Francis’ favored term—that makes possible in us miracles greater even than creation: the work of patient listening and understanding, truth-telling, reconciliation and peace. In Wisdom’s house there is room for all: the poor, the refugee, the forgotten. In my house, she sows forbearance and laughter, dancing around the dinner table to the music of Stevie Wonder, and unexpected courage to do it all over again the next day, when all reserves seem to have run dry. “But she remains unseen, glimpsed only by a few. Sometimes there are none who know her at all.”

My son Isaiah is now 18 and just beginning college. My prayer is that he and young people across the suffering earth will come to know the God of mercy and peace, the God of creation’s astonishing beauty, diversity and gratuitousness. I pray they will come to know the God who frees her children to imagine again, and to imagine together, so that they might face an unsettling horizon with hopefulness and possibility, not in fear and despair. Who will teach them? To whom else shall they go? I pray with Merton’s words: “Gentleness comes to him when he is most helpless and awakens him. Love takes him by the hand, and opens to him the doors of another life, another day.”