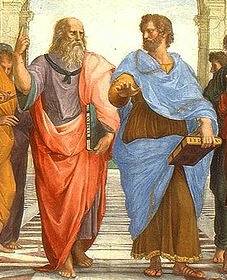

Over at "The Stone," a blog of the New York Times that the paper describes as a "forum for contemporary philosophers and other thinkers on issues both timely and timeless," Rebecca Newberger Goldstein has a fascinating post on the human quest to escape obscurity. In her essay, "What Would Plato Tweet?" Goldstein begins by talking about a conversation with a friend concerning Goldstein's "Klout score." The Klout score derives from a website that calculates a person's online influence. It's the starting point for her ruminations on the human search for "moreness," which led her back to a subject she knows well: the ancient Greeks.

For starters, the Klout on which my friend prided himself struck me as markedly similar to what the Greeks had called kleos. The word comes from the old Homeric word for “I hear,” and it meant a kind of auditory renown. Vulgarly speaking, it was fame. But it also could mean the glorious deed that merited the fame, as well as the poem that sang of the deed and so produced the fame. The medium, the message, and the impact: all merged into one shining concept.Kleos lay very near the core of the Greek value system. Their value system was at least partly motivated, as perhaps all value systems are partly motivated, by the human need to feel as if our lives matter. A little perspective, which the Greeks certainly had, reveals what brief and feeble things our lives are. As the old Jewish joke has it, the food here is terrible — and such small portions! What can we do to give our lives a moreness that will help withstand the eons of time that will soon cover us over, blotting out the fact that we ever existed at all? Really, why did we bother to show up for our existence in the first place? The Greek speakers were as obsessed with this question as we are.

In addition to presenting the Greek positions, she also mentions another of the dominant approaches to self-worth:

Contemporaneous with the Greeks, and right across the Mediterranean from them, was a still obscure tribe that called themselves the Ivrim, the Hebrews, apparently from their word for “over,” since they were over on the other side of the Jordan. And over there they worked out their notion of a covenantal relationship with one of their tribal gods whom they eventually elevated to the position of the one and only God, the Master of the Universe, providing the foundation for both the physical world without and the moral world within. From his position of remotest transcendence, this god nevertheless maintains a rapt interest in human concerns, harboring many intentions directed at us, his creations, who embody nothing less than his reasons for going to the trouble of creating the world ex nihilo. He takes us (almost) as seriously as we take us. Having your life replicated in his all-seeing, all-judging mind, terrifying as the thought might be, would certainly confer a significant quantity of moreness.

You can read her entire essay here.