"Our desires should not be the ultimate arbiters of vocation. Sometimes we should do what we hate, or what most needs doing, and do it as best we can." So writes Gordon Marino, professor of philosophy at St. Olaf's College, at "The Stone," a blog of the New York Times. Marino's comment comes in the midst of a long reflection on the cultural mandate to "do what you love," which might also be expressed as "follow your heart," or what Marino calls the "gospel of self-fufillment." Prof. Marino contrasts this to other ways of framing a career or job search, particularly those ways that involve responding to a need or call, regardless of whether it's what we love or find inherently meaningful. Marino turns to Immanual Kant:

Thinkers as profound as Kant have grappled with this question. In the old days, before the death of God, the faithful believed that their talents were gifts from on high, which they were duty-bound to use in service to others. In his treatise on ethics, “The Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals,” Kant ponders: Suppose a man “finds in himself a talent which might make him a useful man in many respects. But he finds himself in comfortable circumstances and prefers to indulge in pleasure rather than take pains in enlarging his happy natural capacities.” Should he?Kant huffs, no — one cannot possibly will that letting one’s talents rust for the sake of pleasure should be a universal law of nature. “[A]s a rational being,” he writes, “he necessarily wills that his faculties be developed, since they serve him, and have been given him, for all sorts of purposes.” To Kant, it would be irrational to will a world that abided by the law “do what you love.”

Perhaps, unlike Kant, you do not believe that the universe is swimming with purposes. Then is “do what you love,” or “do what you find most meaningful” the first and last commandment? Not necessarily.

Marino touches upon a tension that is very much present in the Judeo-Christian tradition. We often speak about searching for God's will, which some locate in humans' deepest desires. In The Jesuit Guide to (Almost) Everything, Fr. James Martin, S.J., writes that saints and other Christians "find their vocations through natural longings." Of his own decision to leave the corporate track and become a priest, Fr. Martin writes: "[H]ow did this happen? Through desire. At each juncture I was drawn by a desire, an attraction or interest to that life. This is one primary way that we discover what we are meant to do and who we are: desire."

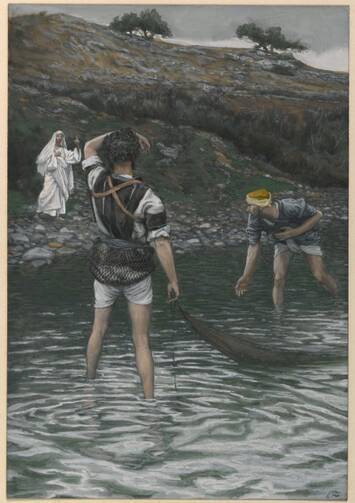

Primary, but not exclusive. Sometimes the call from God doesn't seem best captured in terms of desire, at least not without qualifying that idea heavily. When I think of some of the notable calls in Scripture (e.g., Abraham, Moses, Peter, Mary) it's hard to see how their resulting responsibilities, to which they gave their lives, intersected with their deepest desires. Moses and Mary greeted God's intervention with confusion; and Moses especially didn't seem particularly enthusiastic to confront the Pharaoh. In his objections and demurrals, there's a sense of, "Me? Really?" It seems that at some points, God calls us to do things we don't particularly want or desire, but which for reasons known only to Him, and which unfold over time, we are well suited to do. I think this is part of the heroism of the spiritual life and illustrative of its drama: it's the in spite of element. In spite of what we might want, we yield to God.

Perhaps, though, we have to dig deeper: Perhaps Moses and Mary and other great biblical figures, in ways they didn't even realize, wanted what God asked of them. Perhaps the outward confusion masked a core passion that God alone could set aflame.

Or perhaps they weren't sure what they wanted, but they were generally open to what God would invite them to do. They became, in other words, empty vessels, ready to be filled by his word.

Regardless, none of this is to say we shouldn't mine our deepest desires for God. It is very much worth asking: What, really, in our heart of hearts, do we want? What is it that we long for without qualification, without hesitation, without any doubt?

How can the response to this be anything other than the will of God? What better criteria could there be for our lives?