When Ayham Edris, 2, and his 1-year-old sister, Fatima, arrived at Rome’s Fiumicino airport from Beirut early this morning, they were unable to rejoice like other refugees traveling with them because they cannot see or hear anything. They are suffering from a rare neurological problem that has caused them to lose their sight and hearing.

Their extremely vulnerable situation gained them humanitarian visas and places on the Alitalia flight that brought 101 Syrian refugees from the Lebanon to Italy today, thanks to the Humanitarian Corridors project operated by three Italian Christian bodies—the Community of Sant'Egidio, the Federation of the Italian Protestant Churches and the Waldesian Table—in collaboration with the government of Italy.

The siblings were born in Tripoli, the second largest city in the Lebanon, to a young refugee couple: Abdul Ghaleb Edris, 30, and Souzan Satouf, 19. The couple had lived in Homs, a city in Syria about 90 minutes by car from Tripoli, until April 2013. Abdul was employed in the textile industry until the factory was bombed. Then life became so dangerous from bombings and snipers that for a 15-day period they had no water. They decided to leave the city and flee to Lebanon during a 24-hour truce in the bombing. They convinced the driver of a gasoline truck to take them to the border, and then after much hardship and difficulty they eventually found shelter in a house in Tripoli with other refugees from their hometown.

Abdul managed to get some work as a painter, and they had their first child. The doctors didn’t discover that Ayham had a problem until one month before his birth, but then they misdiagnosed it and gave inappropriate treatment. The second child, Fatima, was born a year later with the same problem. This time, with assistance from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and a Qatari foundation, they got doctors to treat her. But now, after four eye operations, she cannot see anything.

Maria Quinto of the Community of Sant'Egidio had an Italian doctor examine the two children, and then the Humanitarian Corridors organizers decided that they had to bring the children and their parents to Italy in the hope that their problems could be treated.

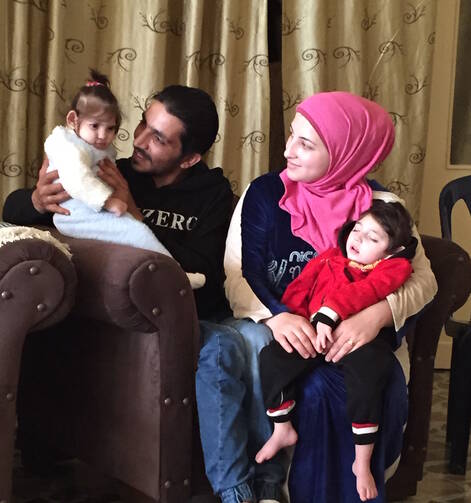

When I met the family in their home in Tripoli on April 30, I was deeply moved as Abdul, sitting in front of me, cradled his little daughter Fatima in his arms and Souzan held her son Ayham in a similar loving way. The children are beautiful, but they could not see us, nor hear anything we said. It was a tragic scene, but the parents are energized by the hope that in Italy their children will receive proper medical care and, perhaps, be cured.

The plight of these siblings brought into sharp focus the vital importance of proper medical care for refugee children with health problems. In Lebanon health care is privatized for the most part. Without money one cannot get proper treatment, and money is something the Syrian refugees living in makeshift shelters or precarious dwellings do not have. Because of their poverty, many health problems of children that could easily be cured if diagnosed in time now turn into major, lifelong complications.

The Humanitarian Corridors project is without doubt making an invaluable contribution to the health and lives of children, like the Edris siblings, who are fortunate enough to come under its umbrella. It must be recognized, however, that in the final analysis this is a small contribution when compared to the vast dimensions of the problem; the project can assist some—but by no means all—of the most vulnerable cases.

At the same time, however, the Humanitarian Corridors project is making a truly important contribution in another way: It is drawing the world’s attention to the disastrous consequences of the ongoing war in Syria on innocent children and on the lives of millions of that country’s inhabitants. It is giving faces and names to the victims of this war; it is refusing to reduce these children and refugee families to mere statistics.

Before the war started in 2011, by all accounts the public health system worked well in Syria. Today it is almost totally destroyed. This was brought home in a stark way three days before I visited the Edris family, when reports from Aleppo announced that the best pediatrician in the city, Dr. Mohammad Wassim Maaz, who had saved the lives of countless children in the city’s war-ravaged neighborhoods, was killed, along with a dentist, three nurses and 22 civilians, when an airstrike hit the Al-Quds hospital where he was working. Eight doctors worked in the hospital, which is supported by Doctors Without Borders and the International Red Cross; now there are only six.

Miskilda Zancada, head of the Doctors Without Borders mission in Syria, told A.F.P. that 95 percent of the doctors in opposition-held parts of the city have either left or been killed. Today, there are only some 70-80 doctors for 250,000 people in the part of the city that is held by the rebels, which the Assad regime is now trying to regain.

The United Nations, for its part, estimates that 400,000 people have been killed since 2011 in this brutal conflict in Syria, including 730 doctors. Hospitals have been destroyed. Many doctors and medical professionals have fled the country, in search of a better life in foreign lands. The situation cannot improve until the war ends.

ADDENDUM: Jesuit Refugee Service in Aleppo Temporarily Suspends Operations Due To Escalating Violence

As I was concluding this article, I received news that the recent escalation of violence—caused by massive attacks with falling shells and explosives—in and around Aleppo, where the Jesuit Refugee Service has a very big operation, has resulted in severe casualties among civilian population, and J.R.S. has suspended its work today (May 3).

Mortar shells fell directly next to the J.R.S. distribution center that serves 18,000 Syrians irrespective of religious affiliation, and also near the J.R.S. clinic that cares for some 2,500 persons. Several mortar shells have fallen on the Al-Rahman Mosque close to the J.R.S. kitchen, which provides hot meals for 6,000 people per day.

While none of the J.R.S. facilities or its personnel have so far been hit by the current spate of violence, the son of a J.R.S. staff member has suffered injury to a kidney, though his medical situation is stable.

Given the escalating violence, J.R.S. regretfully decided today, as a precautionary measure, to suspend immediately its activities related to the distribution center, the clinic and the kitchen. It will evaluate the situation again tomorrow.

J.R.S. is deeply concerned for the safety of the civilian population in Aleppo and, while expressing solidarity with all those affected by the violence, it has called on all warring factions to halt the hostilities immediately and is praying that peace may soon return to this martyred city.

Already last Sunday, May 1, Pope Francis expressed his concern about the violence in Aleppo which, he said, continues to “claim innocent victims, even amongst children, sick people and those who, at the cost of great sacrifice, are bringing aid to those in need.”

He expressed his pain at this spiral of violence, which, he said, “continues to aggravate the already desperate humanitarian situation in the country.” He went on to reiterate his plea for peace in Syria, and appealed to all the parties involved in the conflict to respect the cessation of hostilities and commit themselves to dialogue.