In order to come to terms with the 1838 sale of 272 slaves to two Louisiana businessmen, notable among its other ties to slavery, Georgetown University and the Jesuits of Maryland should offer a formal apology and enact a series of reforms. They include renaming buildings, offering financial aid to the descendants of those slaves and committing new academic resources to study the impact of slavery on campus and in wider society today.

Those are the recommendations of a working group appointed last year by the president of Georgetown University, John DeGioia, which were made public on Sept. 1.

RELATED: An interview with the chair of the Working Group on Slavery, Memory and Reconciliation

“Slavery—slave labor and the slave trade—is part of our history,” the report says. “All of us—students, alumni, faculty, staff, administration, and friends—are the heirs of this history, and all of us must make ourselves its humbled trustees.”

“As a university community, we need to know, to acknowledge, and to absorb that history as part of what makes Georgetown what it is,” it continues.

The group, comprised of 15 members of the faculty, staff and students and chaired by a Jesuit priest, began its work last September, after protests over the university’s decision to retain the name of a building honoring a former university president and Jesuit priest who initiated the slave sale in 1838. The sale generated close to $3 million in today’s dollars to help fund the struggling university.

Beginning last fall, the working group began offering a series of recommendations about how the school and the Jesuits, which founded Georgetown, could acknowledge its past in a meaningful way.

The group said the school’s president and the Jesuit provincial overseeing the Maryland province should begin by offering a formal apology, pointing to examples from St. Pope John Paul II and former President George W. Bush, both of whom apologized on behalf of the entities they represented for past participation in slavery.

“The university, despite the many ways that it has invested resources over the last half century to healing the wounds of racial injustice, has not made such an apology,” the report says.

But, the group said, an apology is only a first step in a years-long process to understand the university’s history with slavery and to begin to reconcile with those who still suffer from it.

“Words along with symbolic actions, such as the naming of buildings, and material investments, such as the foundation of an institute for the study of slavery, work together in making apology a coherent whole,” the report says.

To that end, the group recommends renaming campus buildings that had previously honored two Jesuits and college administrators who were instrumental in the sale of the slaves, Thomas Mulledy, S.J., and William McSherry, S.J.

RELATED: Read the final report here

Last fall, DeGioia accepted the group’s recommendation to strip those names from the buildings and temporarily rename them Freedom Hall and Remembrance Hall. His decision came after a student protest demanding he take action on the matter, convened in part to show solidarity with protests on other campuses over racial unrest.

“We recognized we can’t be complacent anymore,” one of the organizers of the protest, Queen Adesuyi, told The Washington Post last year. “The fact that the sale [of slaves] helped Georgetown to be the prestigious school it is now is an important part of our history that’s important to recognize. It’s a history not being told.”

In their report, the group suggested the buildings be renamed Isaac Hall, honoring the first slave named in the sales agreement, and Anne Marie Becraft Hall, named after an 18th-century African-American Catholic religious sister with roots in the Georgetown neighborhood.

The report suggests that other people associated with the college’s history of slavery who have campus buildings named for them be further studied before taking action. It notes that there was some internal disagreement about trafficking in slavery in the 19th century, with some Jesuits advocating for emancipation.

Statues commemorating the slaves should be erected outside the halls, the report says, along with plaques around campus highlighting the university’s historical relationship to slavery.

“We hope that the two buildings will stand as a reminder of how our university community disregarded the high values of human dignity and education when it came to the plight of enslaved and free African Americans in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries,” the report says.

The group also recommended that the university reach out to slave descendants in both Washington and Louisiana, listening to their needs and assisting with genealogy research, and consider offering descendants admission and financial aid to the university.

“While we acknowledge that the moral debt of slaveholding and the sale of the enslaved people can never be repaid,” the report says, “we are convinced that reparative justice requires a meaningful financial commitment from the university.”

Part of the reconciliation process must include making sure that students of color attending Georgetown feel welcome and part of the community, which, the report says, is not always the case today.

“We believe that significant funding, attention, and resources should be devoted to assessing and improving the racial climate on campus,” the report says. “This should involve racial and ethnic climate surveys, timely responses to the findings, and sensitivity training for all members of the community.”

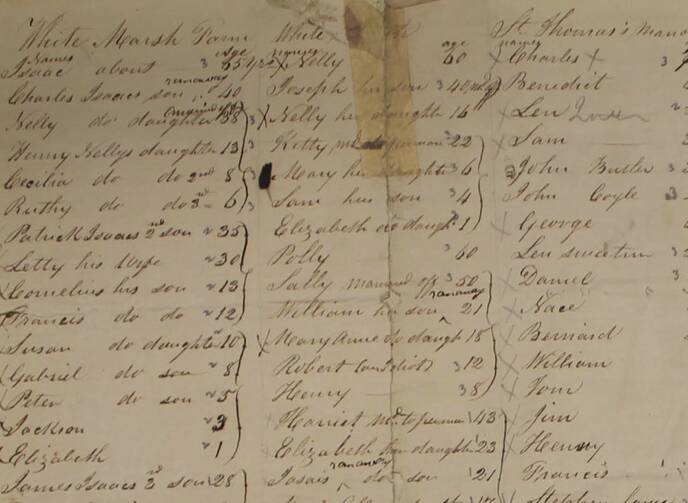

Finally, the report recommends that the university invest in staff to help make the school’s archives on slavery, which includes sacramental records of the sold slaves, available for research, and establish a center to study the ongoing effects of slavery in society.

“We believe that Georgetown’s efforts to engage the task of reconciliation must be institutionalized, and personalized, for the long haul,” it says.

“We are, after all, slavery’s beneficiaries still today. There can be neither justice nor reconciliation until we grasp that truth,” the report concludes.

Update: Thursday, Sept. 1, 12 p.m.

On Thursday, the university announced that it would accept several of the report’s recommendations, including a public apology by way of a “Mass of Reconciliation” and the renaming of two campus buildings that previously honored Jesuits who participated in the 1838 slave sale. The university also said that descendants of the slaves it sold who apply to Georgetown will have their applications weighted in the same way as legacy applicants, who have family members who graduated from the school.

Michael O’Loughlin is the national correspondent for America. Follow him on Twitter at @mikeoloughlin.