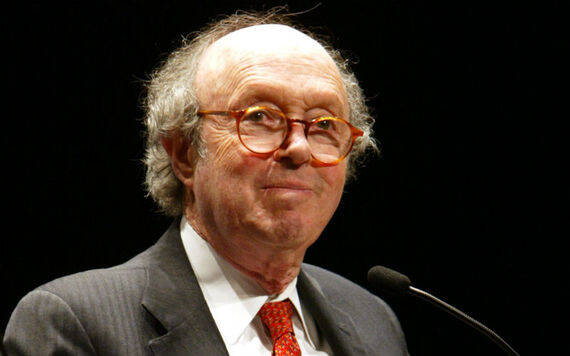

Because I often don’t get to read the Times until late at night, I learned of the New York Times’ legendary op-ed columnist Anthony Lewis’s death in an email from Chris Keating, political reporter for the Hartford Courant, whom I had taught journalism at Fordham and who went on to take Lewis’s course at Columbia Journalism School. I hesitate to assume the honor of claiming Lewis as a friend, but we knew one another pretty well, to the extent that on my invitation he came and spoke at Rockhurst College, the College of the Holy Cross and Loyola University New Orleans, and we enjoyed dinners, long conversations and correspondence.

Chris told me a story I had not heard before. On his first day in Lewis’ course on the Constitution he singled out Chris for a tough grilling on New York Times vs. Sullivan, on libel law, the assignment for the first day. Chris gave a good account, but when he drifted toward analysis, Lewis snapped, “Just the facts.” At the end he summoned a trembling Chris to his desk to declare, “Ray Schroth says hello.” Though I don’t remember exactly how it was set up 30 years ago, I had told Tony that he had one of my students in class: he was free to have some fun.

When I think of Lewis’s character traits, they are those we often associate with saints: compassion, courage, commitment to the weak, honesty, integrity. He was true to his best inner voices. He also wrote brilliantly and clearly about complex issues, usually breaking down the points of a Supreme Court decision and putting them in context so the simplist Times reader could understand it. His two major books — Gideon’s Trumpet, on everyone’s right for a defense in court, and Make No Law, on the First Amendment, which I required of all my students at Fordham — have influenced generations of future journalists and lawyers. Sullivan ruled that a journalist could not be sued by a public official for statements printed critical of office holders, even if the criticisms were incorrect, unless actual malice could be proven. He did not believe however that journalists had a right to refuse to cooperate with the legal investigations when necessary.

After graduating from Harvard, Lewis worked for the Times, then spent four years working on Adlai Stevenson’s campaign, then went to the Washington Daily News, where he won his first Pulitzer Prize for a series of articles on a man unjustly accused of being a security risk. Back on the Times, he was London correspondent, then moved to the op-ed page for 30 years. There he even assumed the freedom to write against some policies of the Times. Nor did he buy into so-called “political correctness,” which seems to grant a long list of minorities freedom from both fair and unfair criticism.

I discovered him in the ‘70s and collected a group of his “Abroad at Home” columns as texts for my students in preparation for Lewis’s Thomas Jefferson Anniversary Lecture at Loyola University New Orleans in April 1993. Some samples:

“In the long run, the nice arguments will not carry much weight against the horror of what will have happened in Bosnia. Bill Clinton will join George [H.W.] Bush as the American President who did not stand up against genocide.” (3/26/93)

“Then there was the murder of three American nuns and a lay church-worker on Dec. 2, 1980. Jeanne Kirkpatrick, who was to become Mr. Reagan’s U.N. Ambassador, said the four had been political activists sympathetic to the Salvadoran guerrillas, as if to suggest that their murder was justified. In March 1981 Secretary of State Alexander Haig told a Congressional hearing that the car in which the nuns were traveling ‘may have tried to run a roadblock’ and that an investigation suggested ‘there’s been an exchange of fire.’ In fact, the women had been shot in the head at close range.” (3/22/93)

“But that is not all there is to remember about Vietnam. The men in Washington knew it was unpopular, and so they turned increasingly to secret means. In their fearful obsession with secrecy they wire-tapped and conducted break-ins and deceived Congress and faked official military records. Nixon even ruled out any explanation of those last twelve bloody days of bombing [of Hanoi]. The end justified the means. Now politicians are talking again about the need for secrecy and covert action and the hard-nosed use of power. And so we must remember: Beware obsession. Beware secrecy. Beware concentrated power. Beware men untouched by the moral consequences of their acts.”(12/21/80)

I discovered in my files the full text of Lewis’s Jefferson Anniversary lecture. I had forgotten that, to my astonishment, it opens with a tribute to me as “a living example of what we are here to think about tonight, freedom of speech.” I am ashamed and embarrassed by the description, not because I do not favor freedom of speech but because I seem to have accomplished so little in that regard, particularly in recent years. Priests, nuns, faculty and guest speakers on Catholic campuses are continually in hot water for saying something not necessarily heretical, but perhaps controversial. Perhaps the new leadership of the church under Pope Francis will acknowledge all the freedoms guaranteed at least to Americans under the First Amendment, including a freedom within the church where all are free to speak out as the Spirit moves them.