There was a time when the American male movie star who could (supposedly) hold his liquor and get through press interviews without whining or emoting was in vogue—from, say, the mid-1940s to the late ’60s. John Wayne was such a figure. Kirk Douglas, Burt Lancaster and Humphrey Bogart were, too. Or take the likes of Jimmy Cagney, Robert Ryan and Lee Marvin—all a combination of menace, resolve and caustic observation. Steve McQueen was more of a transitional figure: sometimes the squinty-eyed man’s man, at others one of those postmodern ironists (think Dustin Hoffman or Warren Beatty) who hijacked pop culture in the 1970s.

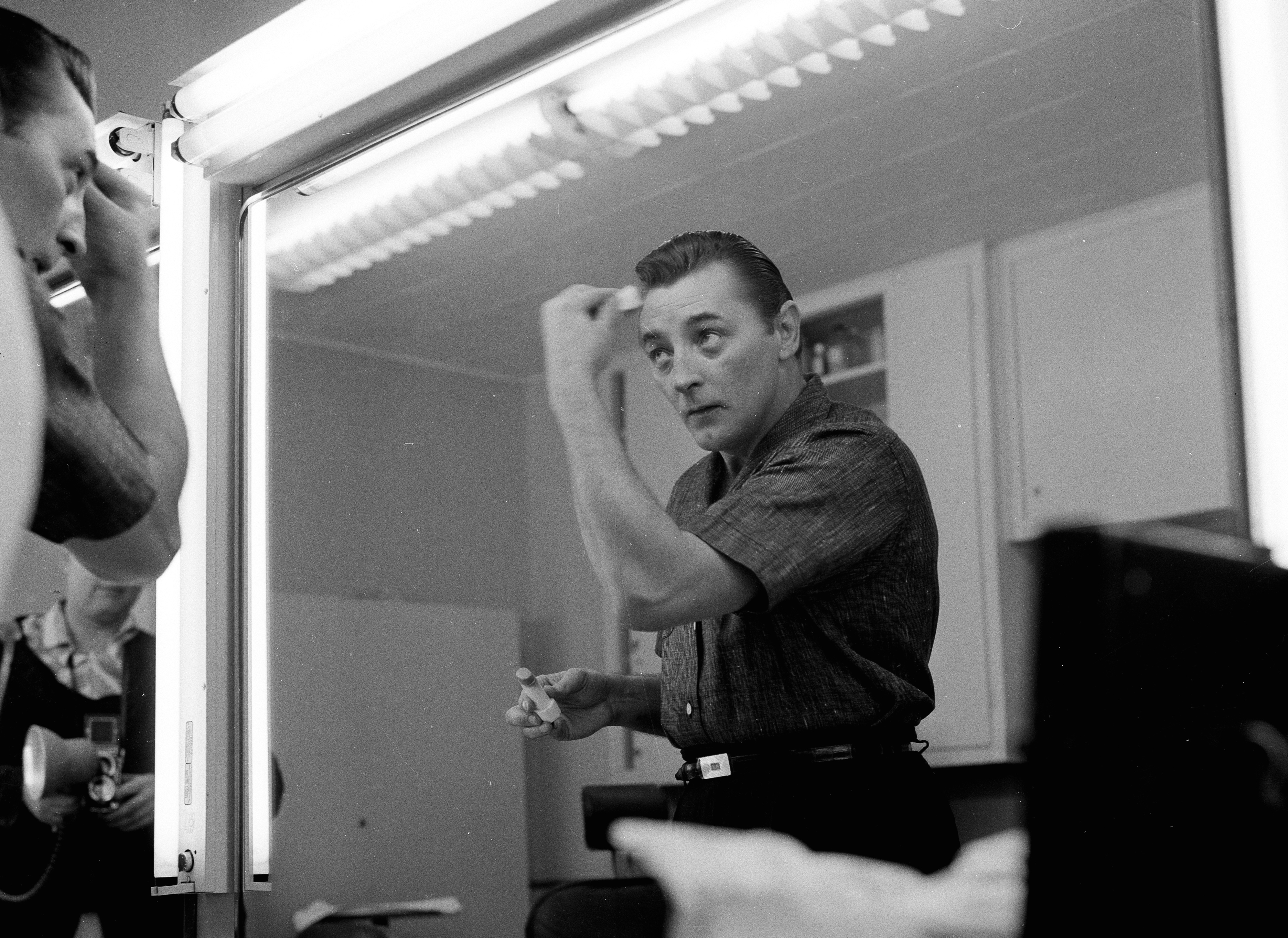

But for sheer old-fashioned cool—a sort of brooding languor, with the ever-present whiff of violence—it would be hard to beat Robert Charles Durman Mitchum, who was born in Bridgeport, Conn., on Aug. 6, 1917. As the concept of masculinity underwent its modern crisis of confidence, Mitchum and one or two other distinguished peers became the face of its remembered spirit: plainspoken, defiant, inherently nostalgic.

How did he do this? In part, by honing his craft to near invisibility. I am reminded of what Robert Wise told me about directing Mitchum in 1948’s “psychological” western “Blood on the Moon.” Wise remembered his young star as having “mastered the art of reacting”:

Mitchum could be standing completely still listening to another guy who would be gesticulating away like Mussolini on a rant, and it would be Bob the audience was looking at. That was really his forte, the still thing, the menace. I picked up Mitchum’s script once and at various points I saw that he’d marked up the phrase “NAR.” I asked him about it, and he told me it stood for No action required. “I don’t need a line,” he’d say. “I’ll give you a look.”

In celebrating the centennial of Mitchum’s birth, we are really paying homage to a peculiarly American male archetype. While some might caricature him as a sort of priapic swinger, loosely connecting the laissez-faire morals associated with the 1950s Beats with those of the Swinging Sixties—a sort of Hugh Hefner with added screen presence—Mitchum transcends the cliché.

An aspiring poet and songwriter, he never lost the classic immigrant’s desire for self-improvement—nor, perhaps, his trademark mixture of ego and insecurity. It is this same tough-and-tender paradox that remains at the core of Mitchum’s character and makes him so compelling to watch on screen.

An aspiring poet and songwriter, Mitchum never lost the classic immigrant’s desire for self-improvement—nor, perhaps, his trademark mixture of ego and insecurity.

It seems fair to say that Mitchum shunned—or at least tactically avoided—anything that might resemble traditional Christian piety, with its twin challenges of self-denial and service. So far as we know, he never attended church, nor ever admitted to any sort of need for an intellectual, institutional or sacramental structure that might enable him to keep the dark side of his personality at bay. And there were dark moments: in addition to arrests for drug use, Mitchum was rightfully pummeled in the press for an interview he gave in 1983 that appeared to deny the Holocaust. (He later apologized saying he was attempting to play a part.)

But Mitchum was open to the works of Christian writers like Thomas à Kempis, who seemed to him to answer both his spiritual and intellectual yearning. He is said to have slept with both a Bible and a bottle of whiskey on his nightstand. These were perhaps the twin totems of his whole life. Mitchum was by both instinct and self-education an acutely sensitive man, whose lifelong affinity was for those he saw as fellow underdogs, yet who resisted the lure of institutional religion.

•••

Mitchum’s mother was a Norwegian immigrant and sea captain’s daughter; his father, of Scottish-Irish and Blackfoot Indian descent, was a shipyard and railroad worker. It seems fair to say that a certain degree of volatility ran in the family. His father died in a railyard accident in South Carolina when Bob was a boy, and he was in and out of school, often involved in fistfights and mischief. He left home at 14 and took to riding around the country on a boxcar.

In time, Mitchum rode the rails to California and found work as a secretary and ghostwriter. He went on to a job working the night shift as a machine operator at Lockheed until a nervous breakdown put him in the hospital. Someone suggested he might look for less demanding employment as an actor, and an agent took him on in the faint hope that he might make it as a cowboy type who “looks kinda mean in the eyes.”

Around the same time, Mitchum married his childhood sweetheart, Dorothy Spence. The bride’s parents did not entirely approve of the match. “They thought Bob was a hobo,” Dorothy later acknowledged. “My father talked of warning him off with a shotgun.” Despite this unpromising start, the Mitchums would be together for the remaining 57 years of Robert’s life.

Meanwhile, Mitchum’s mean eyes got him an audition for the Hopalong Cassidy feature “Hoppy Serves a Writ.” He got the part, along with the two-word motivational advice about finding his inner character: “Don’t shave.”

After notching up seven films in as many months, R.K.O. signed Mitchum to a seven-year deal. The studio memo on the new recruit assessed Mitchum as a “rugged, underplayed type” who “on and off camera is proving himself a team player.” They were right about the first part, if not the second.

Not long after starring in the Oscar-nominated “The Story of G.I. Joe” (like John Wayne before him, he somehow avoided actual combat duty), Mitchum was sitting on his front porch one night when a man pulled up in a car, jumped out and ran towards him shining a flashlight in his face. Then someone else started screaming at him to hold still and put his hands in the air. Mitchum hit the first man in the face, breaking his nose. It turned out his visitors were members of the Los Angeles Police Department investigating a nearby disturbance. The judge gave Mitchum 180 days, at which point the young actor made a counteroffer to join the army instead. He did seven months in uniform, never leaving the United States, got out on a hardship case and went back to Hollywood.

The arrest did not exactly hurt his career. Time magazine eulogized “G.I. Joe” as “a movie without a single false note” and Mitchum himself as possessed of a “profound sense of individuality and danger.” Little did they know. In September 1948, Mitchum was arrested for possession of marijuana “while in the company of a lewd female person not his wife” as the police report put it. He did 43 days on a prison farm and emerged more popular than ever. A bobbysoxers’ fan club—the Mitchum Droolettes—was quickly organized.

Around the middle part of his career, Mitchum gave a variety of outstanding performances that demonstrated a distinct intelligence behind the seemingly blasé facade. In 1955’s “The Night of the Hunter,” he famously plays a charismatic, black-clad itinerant preacher wandering the blue highways in order to do “God’s works.” That Mitchum’s idea of the role might stray from the strictly conventional comes early on in his voice-over rumination: “Sometimes he wondered if God really understood. Not that the Lord minded about their [sinners’] killings. Why, his Book was full of killings. But there were things God did hate.... Preacher would think of these things, and his hands at night would go crawling down under the blankets till the fingers named Love closed around the bone hasp of the knife and his soul rose up in flaming glorious fury.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Mitchum found a niche in film noir, a genre he would adorn right up to the time of 1975’s “Farewell, My Lovely.”

This is surely one of the most creepy moments in cinema history, and taken together with certain of Mitchum’s other deeds in the film, many of them still unsuitable for a family publication, it is remarkable that his young co-stars did not simply break character and run screaming from the set.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Mitchum found a niche in film noir, a genre he would adorn right up to the time of 1975’s “Farewell, My Lovely.” There would be 26 starring features for him in the years 1945-55. Other scripts during this period proved less elevated. “I punch in, I punch out,” Mitchum once remarked. Even so, he was always professional on set. Deborah Kerr remarked of her co-star in 1957’s “Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison”: “He was a poetic, interesting man...a perceptive, amusing person with a great gift for telling a story.... Bob was at all times patient, loyal and sensitive, always in a good humor and always ready to make a joke when things became trying.”

•••

The man of real talent who longs to be acclaimed for something else is a recurring figure in the arts. Mitchum clearly harbored the conceit that he could have earned his keep as a musician or a writer. His chief contribution to 1967’s summer of love, during which he hit 50, was an album of easygoing pop tunes called “That Man Robert Mitchum...Sings.” Shown on the cover wearing a pink shirt and someone’s idea of a friendly smile, the actual tunes have been described as a “hybrid of Dean Martin and Keith Richards, [with] an ambiance of something improvised at a truckstop roadhouse around four in the morning.” Evidently, poetic fires burned bright just below the surface of Mitchum’s flip persona.

In the 1950s the author Barnaby Conrad kept a small hotel in San Francisco, where most of his overnight visitors signed the guest book with comments along the lines of “Thanks!” or “Great place!” When Mitchum checked out, he wrote: “Compadre.... When all the broken crockery of desperate communion is swept from under our understanding heels may we find on that clear expanse of floor the true and irrevocable target of infinite thrust.” It might be unreasonable to assume he hadn’t been drinking. A bit later in his career, he wrote in a young Australian fan’s autograph book, “In a country which with casual aplomb regards the anachronism of the kangaroo and the platypus—the being homo sapiens is a disquieting oddity—Merry Christmas, Bob Mitchum.” Again, it may be that he had overdone the Bacchic rites. But it may also be that Mitchum genuinely felt he had something he wanted to say about the human condition and that as a result, the phrase “intelligent actor” should not be considered an oxymoron in his case.

There were those who believed, in his last years as an upmarket TV soap-opera ham in overblown sagas like “The Winds of War” and “North and South,” that Mitchum had become a parody of himself. Others found his final act oddly poignant, his great face shrunken down until it resembled a sort of acorn surmounted by a pair of comic George Burns glasses. In 1994, when he was diagnosed with emphysema, and someone asked him whether he might not consider downsizing the booze and cigarettes, Mitchum replied emphatically: “Hell, no. I’m not going to change my life just to live another couple of months.”

Robert Mitchum died on July 1, 1997. He was 79, and he went out on his own terms, a half-smoked butt and an empty shot glass on his bedside table. James Stewart followed him just 24 hours later, and some of the critics were thus able to talk about the end of an era. Mitchum himself would likely have scorned those seeking a higher cultural meaning to his life and times. His own preferred epitaph was the old Mexican phrase, Feo, fuerte yformal, which roughly translates as “He was ugly, strong and had dignity.”

Mitchum’s slow, languid smile and air of basic honesty continue to endear him to audiences around the world. He is the embodiment of the guileless American male, fundamentally decent, self-aware and as gritty as a half-finished road.

The author mocks "The Winds of War" but I recommend that people watch it to understand Hitler, Germany and the hell they unleashed on the world in the 1930's. It is available for free to watch on YouTube. It is an epic and celebrates the writings of Herman Wouk, one of the great writers of World War II. By the way Wouk is still alive at 102.

Great article about Robert Mitchum. I learned a great deal about love and eros from Robert Mitchum vis a vis how his characters interacted with the women in his movies. I think especially of "Heaven Knows Mr. Allison" where Mitchum and Deborah Kerr develop a special type of intimacy to survive on an island invaded by Japanese troops during World War II. I started marveling at the mystery in this movie as a boy, watching the film with my family. Being catechized by nuns, I wondered about the scene where Mr. Allison has to remove Sister Angela's clothing/habit because she is drenched to the bone and chilled. When she comes back to consciousness, the portrayed innocent intimacy is masterful acting on both Kerr's and Mitchum's part. I also wonder (as I still watch this movie whenever I can) if the two do marry because clearly they love each other. The ending allows us to go either way on whether or not they stay together forever or not. Powerful. Few movies have such powerful Catholic catechesis as this film. Sister Angela's simple explanations of her faith to Mr. Allison are, for me, quite reminiscent of how my grandmother explained her faith to me. Mitchum pulled this off with brilliance, apologizing respectfully for his ignorance but curious about her faith, nevertheless. Wonderful writing and directing by John Huston.

Excellent piece. Mitcham did a two part episode of the TV show The Equalizer. Catch it if you can. He says very little. His presence is enough.