As Archbishop of Buenos Aires, Jorge Bergoglio recorded a video for the national meeting of Caritas Argentina in 2009 in which he explained the consequences for those who “opt for the poor.” The archbishop said that when you insert yourself into their reality, “your own lifestyle changes. You cannot afford luxuries that before you used to have....”

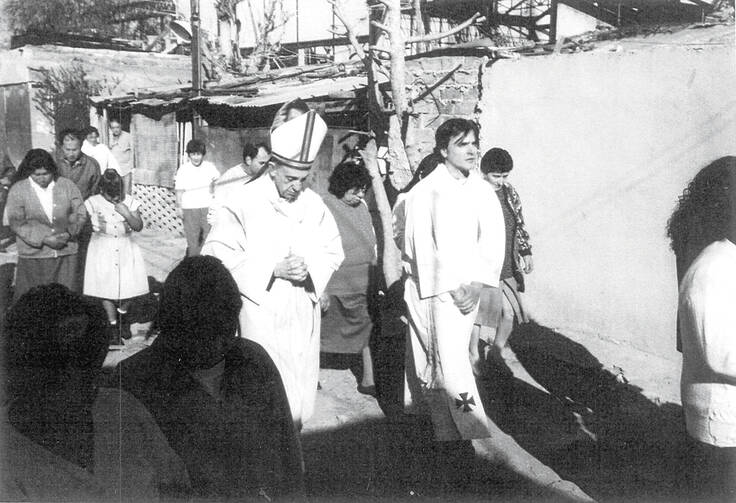

Archbishop Bergoglio understood that to truly know the poor and value their culture one must have a personal connection with them. His connection with the sufferings of the people in the villas miserias—the city slums of Buenos Aires—had evangelized him, teaching him that when disconnected from real experiences of meeting, praying and breaking bread with the poor, concepts about God lack transcendence and relevance.

The “bishop of the slums” is now the bishop of Rome and is calling for the entire church to likewise be evangelized by a deeper encounter with the poor. This vision of a “poor church for the poor” is best understood in the context of the Latin American theology that shaped Jorge Bergoglio and that Pope Francis is incorporating into the teaching of the universal church.

The Place of Encounter

In Latin American theology, popular religiosity is defined as the appropriation of religious beliefs by common people. It is also called popular piety, referring to the way poor people live their religion in contrast with official religiosity and rites.

Although the issue of culture was already present at the Second Vatican Council, that of popular religiosity was not, nor was that of liberation as part of the function of evangelization itself. These two notions were assumed by the magisterium through the Latin American bishops at the Third General Assembly of the Synod of Bishops held in 1974 under the banner “evangelization in the modern world.” At that gathering, bishops from around the world considered the topic of liberation as a function proper to the church’s work of evangelization in each culture. Pope Paul VI incorporated the conclusions of the synod into the formulation of the apostolic exhortation “Evangelii Nuntiandi” in 1975.

In 1985, while rector of the Colegio Máximo de San José in Buenos Aires, then-Father Bergoglio organized the First Congress on Evangelization of Culture and Inculturation of the Gospel. In his keynote address, the archbishop highlighted the importance of the church coming close to the lived experience, or life-world, of the people to generate evangelizing processes capable of impelling social change. His proposal assumed that popular religiosity is the privileged place for getting to know how the poor and common people think and live.

Pope Francis’ apostolic exhortation “The Joy of the Gospel” (2013) builds upon these insights. Drawing on the document of the Fifth General Conference of the Bishops of Latin American and the Caribbean in Aparecida in 2007, the pope recognizes the “popular spirituality” or “people’s mysticism” embodied in everyday expressions of Christian faith as a real locus theologicus capable of evangelizing all people in all places (Nos. 122-26).

Francis’ proposal brings together two lines of thought and action. The first is the evangelization of culture through knowledge of and contact with the popular religiosity of peoples. The second is a liberating pastoral activity driven by a preferential option for poor peoples aimed at promoting social and ecclesial changes, while denouncing all those structures and ways of living—social, economic and ecclesial—that dehumanize by turning people into mere disposable objects.

The Evangelization of Cultures

In Pope Francis’ vision of the church, “the People of God is incarnate in the peoples of the earth” (No. 115). The church must be at the service of each particular people so as to promote its liberation from any internal dependence or external influence, whether political, economic or ideological. The aim is to avoid falling into the temptation of homogenizing the faithful or treating them as a mass with no life or history. To know and serve people implies knowing their origins, their particular way of being and thinking and respecting the fact that “each people is the creator of their own culture and the protagonist of their own history” (No. 122).

With “The Joy of the Gospel” Francis proposes to follow this roadmap and makes clear a theological-pastoral approach inspired by his social, ecclesial and theological experience in Latin America. He thereby introduces into the universal magisterium a notion that comes from Latin American theology, specifically the Argentine theology of the people, namely popular mysticism. The mysticism lived and learned in the popular cultures—especially the experience of poor people—becomes a new center and source of theological reflection (No. 126).

This entails a shift in the present way of being church because it assumes that the most appropriate place of church presence—both pastoral and academic—is in the midst of the poor, serving them and being committed to their struggles and hopes, from the various positions in which we may find ourselves working in the society. That is how the ecclesiastical institution, in everything it is and does, is called to let itself be evangelized by the human disposition that pours forth from the popular mystique, for “the genius of each people receives in its own way the entire Gospel and embodies it in expressions of prayer, fraternity, justice, struggle and celebration” (No. 237).

These are the ways that the poor and lowly relate to God, not only in their own individual needs but in their common vicissitudes or yearnings. These ways of living life can evangelize our fragmented societies and dysfunctional families; they can open our hearts and minds to a wider and healthier understanding of reality, while connecting our lives and works with the sufferings and the hopes of the majority of humankind.

Following the Aparecida document, “The Joy of the Gospel” retrieves the place of popular religiosity in the understanding of this sincere and simple faith that permeates the entire life of the Christian. In the popular mystique we find the Gospel inculturated under this permanent desire to discern the passage of the spirit in the midst of dramas that surround us and that seem impossible to resolve. All these expressions or manifestations—prayer, fraternity, justice, struggle, celebrations—become necessary theological loci for the evangelization of cultures and the scholarly understanding of them; they are not simply worship practices but an intimate experience which overflows into solidarity and need for social justice, a way of living one’s situation in terms of the hope that springs from an intimate and trusting relationship with God. In other words, it identifies the believer’s daily expressions of faith with the suffering Christ, crucified and powerless, but ever on the way toward a better future.

The incorporation of the notion of popular mystique into the universal magisterium through “The Joy of the Gospel” has major ethical implications for ways of life and thinking beyond Latin America. It does not mean that the world of Latin American popular life becomes a paradigm for other cultures. Rather, primacy is granted to the life-world of the poorest in any society, because they are the ethical mediation and the site for reading from the standpoint of God—that is, in the light of God’s merciful gaze—the reality of the contemporary world, its hopes and its shortcomings. But this primacy can be understood only when Christians insert themselves into the popular world of the poor people of their particular societies.

Theology for the People

Latin American theology of the people assumes that reflection on the inculturation of the Gospel is not a problem reserved for pastoral specialists. There is no room for an academic theology that is not connected to the situation of real persons, their daily sufferings and the way they endure hardships out of their faith. Francis’ magisterial reflection comes from this theological-pastoral approach and not from an abstract idea of doctrine that comes before the encounter with the other. Thus, as Francis said last September at a Mass in Havana’s Plaza de la Revolución, “Service is never ideological, since it is not ideas that are served, but persons” (9/20/15).

Otherwise, evangelization and the magisterium itself would run the risk of becoming instruments for instilling doctrine. Lacking this mysticism of living together, theologians would become corporate executives of an abstract knowledge without any saving impact. And the people, especially the poor, would be used for different purposes, from scholarly to business, but would not assume their rightful twofold condition of: 1) being agents of their own history and future and 2) being a critical hermeneutical place of interpretation and confrontation of the Gospel message and the Christian way of life.

The notion of “the people” situates us before the shocking fact of inequality, which is not merely economic disparity in our world but, as St. John Paul II wrote, the existence of different worlds—the first world, second world and third world—“within our one world” (“On Social Concerns,” No. 14). These worlds are ruled by a deplorable imperialist mentality that seeks only to homogenize and impose a single criterion and way of doing things.

This has given rise to new subcultures of poverty characterized by the adaptation and normalization of an exacerbated individualism that creates “people” without any possibilities to live a humane present nor a promising future, people lacking the possibility to have possibilities, in Pope Francis’ words, “masses of people excluded and marginalized: without work, without possibilities, without any means of escape” (“The Joy of the Gospel,” No. 53).

Dire poverty, inequality and the idolatry of money in and between these worlds are facts that can be overcome if we work for the common good and take up the preferential option for the poor. Hence the church is called to become “a poor church for the poor,” to take up the path of encounter and humanization, having as a paradigm the way in which people relate in the popular culture. There exists a mystique of living well that translates into humanizing relations. Pope Francis described this experience in a speech in Bolivia, on July 9, 2015, as...

attachment to the neighborhood, the land, one’s work, the work association. This recognizing oneself in the face of the other, this closeness of everyday life, with its miseries, because they do exist, we have them and their daily heroism. This is what makes it possible to exercise the commandment of love, not on the basis of ideas and concepts but on the basis of the genuine encounter between persons. We need to establish this culture of encounter because neither concepts nor ideas love; it is persons who love.

The religious mystique that springs from the popular culture is the hermeneutical locus par excellence, which makes it possible to overcome the barriers separating popular from academic theology, or the faith of the poor, who live in the midst of the vicissitudes of everyday life, from the ecclesiastical institution and its official liturgy. It makes it possible, moreover, to understand that the evangelization of cultures proceeds by way of inserting oneself—both personally and institutionally—into the life-world of those on the margins and working for the integral liberation of all in this globalized world. It means expanding our relationships and moving out of our comfort zone. As Francis states in the letter he wrote to Cardinal Aurelio Poli for the 100th anniversary of the Catholic University of Argentina:

Do not be satisfied with an office theology. May your reflection be done on the borders.... Good theologians, like good shepherds, smell like people and the street, and with their thinking, pour ointment and wine into the wounds of people.