On Ash Wednesday, the children’s service at St. Philip’s Episcopal Church lasts only half an hour. We designed this service to use language that is accessible to young people, but it sacrifices none of the elements of traditional worship. Older children read the Lectionary passages for the day, repeating the prophet Joel’s call to “rend your hearts and not your clothing” and to “return to the Lord your God.” As the lector prays Psalm 103, reminding us that God “knows whereof we are made; he remembers that we are but dust,” the whole congregation repeats the antiphon, “The Lord is merciful and gracious.” By the final verse, even toddlers are chiming in, in a chorus that is truly precious.

But the children are not there to be precious. Like the adults who accompany them, they are in church on Ash Wednesday to, in the words of the children’s liturgy, “prepare our hearts for the great mystery of Easter.” We ask them to make sacrifices to that end. The invitation to keep a holy Lent asks everyone present “to think about how you can love God more deeply. Think about those things for which you are sorry, pray daily, and offer acts of kindness that will help others and be a sign of your love for God.” The prayer over the ashes focuses our attention on the season’s promise: “May the ashes placed on our heads remind us that our life on earth is temporary, but because God loves us, we will live with God forever.”

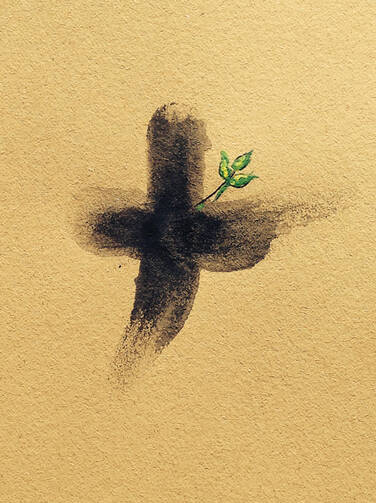

Then comes the moment when, in my role as associate rector, I take the ashes and prepare to walk around the congregation, gathered in a circle. And as this moment arrives, I swallow hard, because in that circle, life and death are visibly intertwined. I utter the words: “Remember that you are dust, and to dust you shall return.” They are words that bring us down to earth. Repeated as ashen crosses are signed on forehead after forehead, they remind us of our uniquely human fate: to die one day, as all creatures must, but alone among those creatures, to know that death is coming. Taken out of context, these words might be depressing. On Ash Wednesday, they invite us to prepare our bodies, souls and minds not only for the death that Holy Week will bring, but also for the resurrection we will celebrate on Easter morning.

Christians stake everything on the revelation that death is the pathway to new life, but sometimes we need to see life and death standing side by side to understand fully the cost and the promise of that mysterious reality. And that is not easy.

Before me stands a boy conceived years after his parents lost their first child to cancer. Next is a little girl whose baby brother was stillborn. There are families complicated by divorce and enriched by adoption. Infants too young to hold up their heads sit propped on a parent’s arm. I mark each of them with a cross of ashes, exhorting solemn children, gurgling babies and adults of all ages alike to “Remember that you are dust, and to dust you shall return.”

Every year, I finish the service with tears in my eyes. Every time, I am struck by the trust parents show by bringing their children to be marked. It is hard to accept the fact that our children will return to dust. But Christian faith not only tells that truth, it calls disciples of Christ to raise our children in light of it. It calls us not to fear death, but to cherish life, knowing that it can be painfully short, yet trusting in Easter’s promise that our lives with God will be wonderfully long.

The trust parents show on Ash Wednesday is the same trust they display at their children’s baptism. When I baptize infants, I ask parents not to hold their own baby as I pour the water, but instead, to place the child in my arms. That simple physical act embodies a theological truth: that parents are committing their child to a larger household than their own, in which relative strangers share responsibility for each other’s souls and bodies. Within that household, we help each other die to sin, and we remind each other of the daily reality of resurrection, as together we seek the reign of God.

Children are more honest than adults about the resistance to death that we all share. I heard that resistance spoken aloud when, several years ago, I baptized Caleb, a 9-year-old boy with autism. Caleb’s parents had explained that baptism would make him a member of Jesus’ family. Looking forward to that, he leaned happily over the font. But after the water ritual, as he heard me give thanks that God had “raised him to the new life of grace,” fear seized Caleb. His scream echoed through the church: “I don’t want to die! I don’t want a new life!” His parents and I soothed him until he let me sign a cross on his forehead with holy oil, when he smiled at being “marked as Christ’s own forever.” Once Caleb was reassured that his new life had already begun, he went gladly to the Lord’s Table to share Communion with his birth family and the larger household of the church.

Caleb was honest enough to speak the truth most of us avoid. We don’t want to die; we don’t want a new life. I don’t like placing ashes on babies’ foreheads. But I do it, at their parents’ invitation and in view of the whole congregation. Those ashen crosses are a sign that together we are raising these babies to trust the merciful and gracious God who remembers that we are but dust, and who promises that this precious dust will live forever.