Part of the answer is that Lonergan is just plain hard; he ambitiously sought to bring theology into conversation with modern physics, mathematics, economics and cognitive theory. Another problem is that although Lonergan placed great store by communication, he himself did not excel in that area. An equally serious impediment has been that philosophers treat Lonergan as a theologian, and theologians treat him as a philosopher. Social scientists by and large have recognized him as neither, for his work does not fall into any well-defined school.

Thus Lonergan, who modestly described himself as a methodologist, falls between the cracks of artificially fragmented disciplines. As a result, with Lonergans magnum opus, Insight, reaching its 50th anniversary this year, the question that will be increasingly posed when his name is mentioned is: Why is (or was) Lonergan considered a great Catholic thinker; and what, if anything, does he have to say to the times we live in now?

As the workshop ended, I sat down with another participant, Gerard Whelan, S.J., who teaches theology at the Gregorian University in Rome. We tried to figure out why it was so difficult to answer that question, even for those of us who have benefited greatly from his work. We began searching for Bernard Lonergan.

The Invisible Man

Were there clues, perhaps, in the workshop presentations? A professor of English literature had given a spellbinding analysis of themes of human authenticity and religious experience in T. S. Eliots Four Quartets. A philosopher engaged in debates about the ethics of stem cell research spoke of the fact that many scientists and moral philosophers uncritically accept the argument that a fetus cannot be a human person until it looks like one, even though the tiniest embryo already contains all the elements of a unique individual. Another presenter discussed how Edith Stein had studied the thought of Charles Darwin and sought, in Germany during the 1930s, to update Catholic teaching on the natural sciences. A business school professor spoke of the blind spots (Lonergan called them scotomas) that get in the way of understanding what is actually happening in an ongoing business organization. One evening was devoted to hearing about the work of the SantEgidio community, a relatively new movement of Catholic lay people that has achieved notable success in mediating peace agreements in troubled developing countries. Father Whelan spoke of how he came, during six years as a missionary priest in Africa, to discern defects in certain tendencies within liberation theology.

All of these speakers credited Lonergan for helping them to make breakthroughs of various sorts in their own fields, but Bernard Lonergan himself remained nearly invisible as they discussed the discoveries they had made. Why was this? The answer lies in Lonergans daunting book, Insight: A Study of Human Understanding. There he describes what we experience as a breakthrough or insight as situated within the dynamic structure of human cognition: the recurring and cumulative processes of experiencing, understanding and judging. That process of knowing is the same whether the knower is a scientist, an artist, a theologian, a political theorist, a lawyer or a child learning how to walk and speak. The process regularly generates aha moments, not only on rare occasions in the minds of great geniuses, but in the minds of all men and women every day in the course of our ongoing mental operations. As we go about our daily business, we attend to the data of sense and experience. Our intelligence leads us to wonder and to formulate questions. (At least that is the way it is supposed to work. Lonergan once remarked to some lethargic students: If you dont wonder, you wont try to understand; youll just gawk!) Once we begin to wonder, though, were off to the races, for insights, far from being rare occurrences, are as natural to human beings as breathing.

Good Insights and Bad

The quality of any given insight, Lonergan taught, depends on the quality of mind and material involved in this process. Not everyones mental equipment is as powerful as Lonergans, and not every bright idea that pops into ones head in the shower is worth proclaiming to the world. Insights, Lonergan said, are a dime a dozen. Some are duds. So we reflect on our insights. We sort them out. We marshal the evidence; we talk it over; we test the new idea against what we know; we investigate its presuppositions and implications; we give further questions a chance to arise; and eventually we make a judgment whether to affirm or doubt it. Insights accumulate into viewpoints, patterned contexts for experiencing, understanding and judging.

Over time, the recurrent, cumulative and potentially self-correcting processes of experiencing, wondering, understanding, critically evaluating, judging and choosing may enable us to overcome some of our own errors and biases, the errors and biases of our culture, and the errors and biases embedded in the data we received from those who have gone before us. The seed of intellectual curiosity has to grow into a rugged tree to hold its own against the desires and fears, conations and appetites, drives and interests, that inhabit the heart of man, Lonergan wrote in Insight. As our insights accumulate and form patterns permitting a better integration of what we have learned, our horizon shifts. When we move to a higher viewpoint, we become aware of a certain rearrangement of all that we have ever known, a certain transformation of our very selves. Parts of the past assume a new relation to one another; feelings change; doors open in the mind and heart. Sometimes the change is so great that when we try to express what has occurred, we use words like conversion and redemption.

The speakers in the Lonergan workshop were, in their different ways, describing how their personal appropriation of these processes enabled them to make certain advances. Father Whelan and I concluded that the reason Lonergans influence on them was hard to discern was that what they had learned from him was how to make better use of their own minds, to become conscious of what they were doing when they were knowing, to think in terms of development and schemes of recurrence, to notice what is going forward in their various disciplines and to become more aware of the biases that can distort ones perceptions and analyses. As one Lonergan expert put it, He introduces people to themselves in a unique way.

A Bloody Entrance

In other words, searching for Bernard Lonergan leads one down an endless path of attending to experience, reflecting on it and coming to judgments, which again must be tested by reason and experience. The path is a rocky one, a struggle all the way. As Lonergan has written in Insight: Even with talent, knowledge makes a slow, if not a bloody entrance. To learn thoroughly is a vast undertaking that calls for relentless perseverance. To strike out on a new line and become more than a weekend celebrity calls for years in which ones living is more or less constantly absorbed in the effort to understand, in which ones understanding gradually works round and up a spiral of viewpoints....

What message then, does Lonergan have for the times we live in now? Father Whelan and I do not consider ourselves experts on the mans vast body of work, so we hope the ideas that came out of our conversation will stimulate other reflections on why Lonergans thought continues to be compelling. But for us the message is something like what Socrates said to his grieving friends when they asked what they were to do when he left them: Greece is a vast land, Cebes. I suppose there are good people in itand there are many races of barbarians too. You must search in company with one another, too, for perhaps you wouldnt find anyone more able to do this than yourselves.

Who Was Bernard Lonergan?

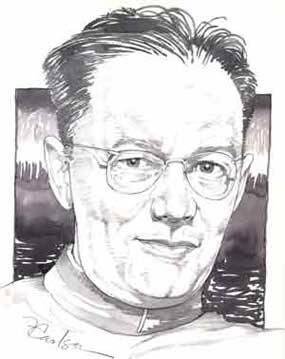

Bernard Lonergan was born in Buckingham, Ontario, on Dec. 17, 1904, and entered the Society of Jesus at Guelph, Ontario, on July 22, 1922. He studied philosophy at Heythrop College in England, where according to Msgr. Richard M. Liddy (The Mystery of Lonergan, America, 10/11/04), he took refuge in the work of John Henry Newman, especially his Grammar of Assent. Newmans remark that ten thousand difficulties do not make a doubt has served me in good stead, Lonergan once wrote. It encouraged me to look difficulties squarely in the eye, while not letting them interfere with my vocation or my faith.

In 1933 Lonergan traveled to Rome to study at the Pontifical Gregorian University, where he wrote his doctoral dissertation on Thomas Aquinass teachings on grace. One of his teachers was Bernard Leeming, S.J.

It was in one of Leemings classes that Lonergan experienced the intellectual conversion that would shape the rest of his career. Liddy described Lonergans fundamental insight as a clarity and distinctness of apprehension of the human act of understanding as the door to reality.

Lonergan explored these themes in his two major works, Insight (1957) and Method in Theology (1972). After leaving Rome Lonergan went on to teach at Loyola College Montreal, the University of Toronto and Boston College. He died on Nov. 26, 1984.

Since his death, a Lonergan network has blossomed around the world. His work is studied at centers in Boston, Washington, D.C., Los Angeles, Ottawa, Sydney, Dublin and Naples.

Every year there are conferences devoted to the exploration of his thought, and the papers and dissertations on his work continue to multiply. The University of Toronto Press has teamed up with the Lonergan Research Institute in Toronto to publish the Collected Works of Bernard Lonergan, a 25-volume set, of which 13 volumes have appeared to date.