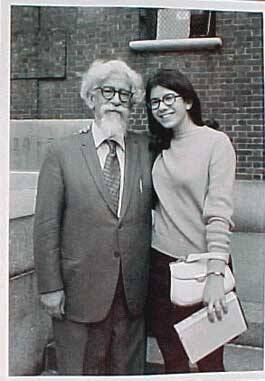

Susannah Heschel, the daughter of one of the foremost 20th-century Jewish thinkers, Abraham Joshua Heschel (1907-72), holds the Eli Black Chair in Jewish Studies at Dartmouth College. Last March she visited Poland to honor Stanislaw Musial, S.J. (1938-2004), a Jesuit of the Southern Poland Province, for his work in Jewish-Christian relations. The interview was conducted there by Doris Donnelly, professor of theology and director of the Cardinal Suenens Center at John Carroll University in Cleveland, Ohio, and John Pawlikowski, O.S.M., professor of ethics and director of the Catholic-Jewish Studies Program of the Bernardin Center at the Catholic Theological Union in Chicago.

What led you to accept our invitation to Poland?

My father was born in Warsaw in 1907, one hundred years ago this year, into a family recognized as spiritual nobility in the Jewish world. Because he descended from prominent Hasidic rabbis, even as a child he was regarded as a genius by adults, who would rise when he entered a room. With the rise of Hitler, the world my father knew, the world that had nourished him, disappeared. My father was fortunate to get an American visa in 1939, just six weeks before the Nazis invaded Poland, and he never again returned. I owe my existence to Poland. I wanted very much to come on my fathers anniversary and at the same time to honor Father Musial, whom I knew.

Did your father use his visa to come to New York?

Actually, his first position in the States was at the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati. The college had very little money, but they provided the visa, and their invitation saved his life. He arrived in 1940 and it was a very difficult time for him. He earned $500 a year and lived in a dormitory, where he had a little refrigerator so that he could prepare his own meals because the cafeteria was not kosher. He was lonely, poor, did not know English and was desperately trying to obtain visas for other members of his family and friends. He found his students odd and they found him odd as well. They were also not as well prepared as his students in Germany.

Did the family he left behind in Europe survive?

Only those who fled before the war survived. His mother, sisters and other relatives were all murdered.

How do you suppose he was able to manage the sadness?

There is a phrase in the Zohar that says only someone with a broken heart is a whole person. It is a very cryptic statement, and one of the interpretations is that when the heart is broken, then the Shekinah, Gods presence, comes and fills it.

I also think there are certain qualities of personality that go together with being a religious person, a person who prays. When my father got upset or discouraged, he never held on to a bad feeling. He would move on. He had a capacity to overcome depression and despair.

You referred to your fathers German students....

My father did his doctoral studies in Germany and also taught in Berlin in both Orthodox and Reform rabbinical schools. He loved Berlin and would have been happy to spend the rest of his life there. But he finished his dissertation on prophetic consciousness just as Hitler came into power. Soon, because he was Jewish, the issue of having his work publisheda requirement for getting the doctorateran into serious difficulties. Fortunately, the Polish Academy of Sciences in Krakow agreed to publish his dissertation, and by exception it was accepted at the University of Berlin as fulfilling requirements even though it was printed outside Germany.

Did he stay long in Cincinnati?

Long enough to meet my mother, Sylvia Straus (1913-2007), a concert pianist. They fell in love and were married in 1946. She continued her piano studies in New York, and my father accepted a position at Jewish Theological Seminary, also in New York City.

Were things happier there?

Not really. At Jewish Theological Seminary, for a long time he was allowed to teach only undergraduate students, those preparing to be teachers, and not the rabbinical students. His field was Jewish theology, which at the time was regarded as unimportant by many members of the faculty. Very rarely was he offered an aliyah to the Torah (the honor of reciting a blessing over the Torah reading) at the seminarys synagogue services, and never in his 27 years there was he asked to deliver a sermonan honor frequently given to students but not to him. Because of academic politics, he was also not permitted to sit in the front row of the synagogue.

One of his former students, now a rabbi, told me with embarrassment that students read newspapers while Rabbi Heschel was lecturing. They mirrored the disrespect many of the faculty had for my father. Students even complained when my father cancelled classes to march in Selma; other faculty members routinely rescheduled classes when they had to be away.

It should be said, though, that my father was not singled out for rude treatment. There were other accomplished scholars who also suffered the jealousies and pettiness of academic life. Some left Jewish Theological Seminary. My father was hurt and dismayed, but he stayed.

It sounds like the classic story of the prophet not honored among his own.

It is true that the more he was excluded at J.T.S., the more he was invited and honored elsewhere. One important event was Reinhold Niebhurs enthusiastic review of Man Is Not Alone (1951) in a Sunday edition of the New York Herald Tribune. Of Abraham Heschel, Niebhur wrote, It is a safe guess that he will become a commanding and authoritative voice not only in the Jewish community but in the religious life of America. Imagine, my father had experienced an all-out effort in Germany in 1933 to get rid of the Old Testament from the Christian Bible, to make the Bible Judenrein (purged of any Jewish influence), and then comes this glorious review!

When it appeared, my parents, in their naïveté, expected calls from colleagues to say mazel tov and congratulations, but none came. It was their first experience of academic stinginess, and they were shocked. Reinhold Niebhur and my father, however, became very good friends. My father said that no one understood his work better than Niebhur; and Niebhur, in a touching expression of friendship, asked my father to deliver the eulogy at his funeral.

Your father was also honored by Catholics, isnt that so?

Yes, yes, he had many friends among Catholics. He was deeply impressed by Cardinal Augustin Bea and Cardinal Johannes Willebrands, both tireless supporters of dialogue with non-Christians. He spoke highly of the Jesuit priest Gustave Weigel and adored the University of Notre Dames president, Theodore Hesburgh, C.S.C. Notre Dame, among other Catholic colleges, gave my father an honorary degree.

Some of his friendships with Catholics came about because of his involvement with Nostra Aetate, the Second Vatican Councils Declaration on the Relationship of the Church to Non-Christian Religions. Some bishops insisted that the ultimate conversion of Jews be included in the final version of the document. My fathers objection was unequivocal: the phrase had to be eliminated. If faced with the alternative of conversion or death, he said, he would rather go to Auschwitz. I was terrified when I heard him say this. My father met with Pope Paul VI to make his objection clear, and he said many times that he was told after their meeting that the pope took his pen and crossed out the sentence.

Other Catholic friendships came about because of a common, unwavering belief that the Vietnam War was a moral outrage. For my father politics and religion were inextricably connected, and he became an outspoken critic of American foreign policy and the mind-boggling reticence of the religious community to declare the war an unmitigated evil. He said many times that people have a will to be deceived and politicians know how to manipulate that will. The lies of politicians were abhorrent to him; even more was the gullibility of Americans. He could not separate religion and politics. Political issues were moral issues, religious imperativesthat was the message I received constantly at home. At a demonstration against the war, someone asked him why he was there. His answer: I am here because I cannot pray. In a free society, some are guilty but all are responsible was his mantra; it galvanized the imagination and action of manyCatholics, Protestants and Jews.

My father said that Christians understood his work better than Jews. He had more positivemore intelligentreception from Christians. My father particularly enjoyed lecturing at Catholic universities. There was such warmth and hospitality, friendship, humor and laughter on these occasions. And often, when he returned to his room, there would be a bottle of brandy waiting for him.

How did the Jewish community react to your fathers involvement at the council and among Catholics?

A few made their displeasure known: Who are you to be the representative of the Jews? and If you want to see the pope, let the pope come to you. My father had a wider view of the importance of friendships for the future of Jewish-Christian relations, and he always put things in a historical perspective. Of course, there were Jews who were grateful to my father for his interfaith commitment.

Was the political-moral connection the reason he went to Selma and aligned himself with the civil rights movement?

Absolutely. Racism in America was a grave moral issue. My father shared with Martin Luther King Jr., an understanding of God as the most moved mover. He disabled the image of the God of the Old Testament as a God of wrath by pointing out that God has passionanger, yes, but also tenderness, affection and forgivenessand responds constantly to us.

For my father, religion may begin with a sense of mystery, awe, wonder and fear, but religion itself is concerned with what we do with those feelings. Religion evokes obligation and the certainty that something is asked of us, that there are ends which are in need of us. God, he once wrote, is not only a power we depend on; He is a God who demands. God poses a challenge to go beyond ourselvesand it is precisely that going beyond, that awareness of challenge, that constitutes our being. We often forget this, so prayer comes as a reminder that over and above personal problems there is an objective challenge to overcome inequity, helplessness, suffering, carelessness and oppression.

My father understood Gods passion for us, and our partnership with God, as divine pathos. The civil rights movement was a privileged place for us to accept the challenge for justice.

How did your father see himself institutionally?

He never labeled himself with any of the movements, and he freely criticized all of them: not enough halakha (law), not enough agada (story); too much focus on having big synagogues, a reflection of an edifice complex; religion in decline because the theology was insipid; Jews as messengers who forgot the message. Always observant, he was nonetheless insistent that we cannot live as Jews today the way we lived yesterday. Change is imperative. Like Pope John XXIII, whom he quoted, he realized that no edifice, no religion, could survive without repair from time to time.

Theres an expression Jewish people sometimes use. Theyll say someone is strictly observant. It occurs to me that the word strict just doesnt fit my father. He was not about being strict. Im not sure what the right expression might be, but lovingly observant might be it.

When I left home and went into the world, I discovered people were different from my family. I was surprised that some Jews who kept the Sabbath worried about fine points of Jewish law. We never did that at home. Things were so much more natural. Observance was the breath of life. It was how we lived.

Did your father know the philosopher Martin Buber?

My father met Martin Buber in 1936, when he was in his 20s and Buber in his 50s. Of course, he looked up to Buber and was excited to be invited to his home. He wrote a letter to a friend describing the meeting and a debate they had over tea. Buber said whats important in Jewish education is to teach people the words of the prayer book, to teach them the prayers to recite. My father said no, whats important is to teach people the meaning of prayer, how to pray.

My father thought of prayer as not an occasional exercise but rather like an established residence, a home for the innermost self. In his essay On Prayer, he says that all things have a home: the bee has a hive, the bird has a nest. For the soul, home is where prayer is, and a soul without prayer is a soul without a home. Continuity, permanence, intimacy, authenticity and earnestness are its attributes. I enter [this home] as a supplicant and emerge as a witness; I enter as a stranger and emerge as next of kin. I may enter spiritually shapeless, inwardly disfigured and emerge wholly changed. We pray because there is a vast disproportion between human misery and human compassion. We pray, he said, because our grasp of the depth of suffering is comparable to the grasp of a butterfly flying over the Grand Canyon.

How did your father respond to the work of the German-American theologian Paul Tillich?

My father came to theology with a point of view opposite to that of Paul Tillich. Tillich spoke of faith in terms of ultimate concern whereas my father spoke of faith in terms of ultimate embarrassment: the awareness of the incongruity of character and challenge, of perceptivity and reality, of knowledge and understanding, of mystery and comprehension. For him, loss of face is the beginning of faith. There is no self-assurance or complacency in a religious person. A religious person could never say, I am a good person. A religious person is always questioning, challenging, never satisfied. He wrote, I am afraid of people who are never embarrassed at their own pettiness, prejudices, envy, and conceit, never embarrassed at the profanation of life. Embarrassment is meant to be productive; the end of embarrassment would be a callousness that would mark the end of humanity.

One of your fathers most celebrated books is The Sabbath; is there an insight you can single out from your home celebration of Sabbath?

I have written about this in the preface to the new edition of The Sabbath, which is to be published soon. There are some helpful Sabbath lawsthe shutting out of secular demands and refraining from work. In enumerating the categories that constitute work, the Mishnah presents types of activities necessary to build technological civilization. My father went further. Not only is it forbidden to light a fire on the Sabbath, but, he wrote, Ye shall kindle no firenot even the fire of righteous indignation. In our home, certain topics were avoided on the Sabbath (politics, the Holocaust, the war in Vietnam) while others were emphasized. Observing the Sabbath is not only about refraining from work, but about creating menuha, a restfulness that is also a celebration. The Sabbath is a day for body as well as soul. It is a sin to be sad on the Sabbath, a lesson my father often repeated and always observed.

Was there something your father did not live to see, something you think he wished he could have done before he died?

My father died before Jim and I were married, but he had a wish to dance at my wedding. He told me that often. There is a very obscure passage in the Zohar that says on your wedding day, if a parent has died, God goes to the Garden of Eden and personally escorts the soul of your parent to your wedding to stand under your wedding canopy. My father often told me, when I stand under my chupa all of my ancestors will stand with me. Its a very old tradition, and I think it happened at my wedding.