Once a month Sister Barbara Flannery waits outside a door for about two hours. On the other side is a support group for people sexually abused as minors by priests. I’m there, hanging around, said Sister Flannery, chancellor of the Diocese of Oakland, Calif., and a member of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet. Sister Flannery and a priest who was abused as a minor are waiting around in case the group wants to talk to them. She told Catholic News Service in a telephone interview that sometimes they are invited in to discuss spiritual issues or are approached by an individual afterward.

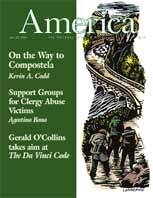

The diocese organized and finances the support group. Other dioceses around the United States also are organizing support groups as part of their outreach services to victims of sexual abuse by members of the clergy. Participation in support groups composed of victims who talk among themselves is often an important way for victims to release the anger and pain locked inside them.

Victims need to repeat their stories many times to release the anguish they feel, said Herminia Shea, a licensed psychologist in California who has organized a victims’ support group for the Diocese of Orange, Calif. Family and friends can hear the story one time, but it is hard to listen to it over and over, she said. The diocese also sponsors a support group, organized by another licensed psychologist, that is solely for relatives of victims.

Few people who have not been abused can understand what a victim is going through, said Shea. In a victims’ support group, participants talk among themselves and are able to express their feelings and frustrations with no fear or shame, she said. They learn that other people have gone through the same thing, so they don’t feel so alone, said Shea.

Somebody understands what you are going through. This is important for healing, Shea said. In any trauma, you are trying to make sense to yourself of what you are going through.... When you see you have a mirror in someone else, you connect with the outside world, she said.

Shea describes her role at the group sessions as a facilitator, who provides an environment where people feel safe to express themselves freely without feeling threatened. Shea said that support groups are helpful, but the meetings are not therapy sessions. They should be understood as complementary to private therapy, as each individual has personal needs and develops at different stages, she said. Dropouts are normal. No group can fit everyone’s need, Shea said.

Bernard Nojadera, director of the Office for the Protection of Children and Vulnerable Adults of the Diocese of San Jose, Calif., said his diocese organized a support group; but it no longer meets, because the members decided it would be better to continue with their personal therapy first. One survivor said he had anger issues he needed to confront before he could be useful to others, said Nojadera.

Barbara Elordi, pastoral outreach coordinator for the Archdiocese of San Francisco, said that support groups provide a setting in which victims have the opportunity to progress with their lives. Clinically, it’s a place where they feel hope and experience movement forward, said Elordi. We make clear we don’t want them stuck in place, she said. Through a support group, victims can network with one another, she said. As people get more healed, they can get together for more things.

The U.S. bishops’ Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People (June 2002) tells dioceses to offer programs such as counseling, spiritual assistance, support groups and other services mutually agreed upon by victims and church officials. But the path to church services is often rough terrain for victims, as many are still hesitant to trust the institution they felt betrayed them, said victims and diocesan officials interviewed by Catholic News Service. Important to success is overcoming mistrust and involving victims in the development of programs, they said.

Bernard Nojadera went to a local meeting of Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests and passed out his card. At first people clammed up. I told them: I represent the diocese, which wants to make things right. We want to offer whatever we can,’ said Nojadera. Now, three victims and several wives of victims are on the San Jose Diocese’s 24-member lay pastoral outreach committee, he said.

Cooperating with victims is crucial in developing programs because of the high degree of sensitivity felt by victims, said Terrie Light, a victim who has worked with the Diocese of Oakland, Calif. Most people working for the church do not understand these sensitivities unless they have been highly trained, said Light, who is licensed in California as a marriage and family therapist. Church people just don’t know what survivors want. (Many church officials and people who have been abused use the term survivor to describe a victim of sexual abuse by clergy.)

Light praised the Oakland Diocese for starting a dialogue with survivors in the late 1990’s. One result was a healing prayer service held in 2000, in which the diocesan bishop at the time, John S. Cummins, apologized to victims and to the entire church community. This service of apology was created by the survivors. We wrote the words we wanted them [church leaders] to say, said Light, who was living in the Oakland Diocese when she was abused. She still lives in the area.

Several other dioceses have held similar liturgies.

Sister Barbara Flannery, the Oakland diocesan chancellor, said she would like to have reconciliation services in 2004 in each parish where abuse occurred. One survivor termed this an exorcism of the place,’ said Sister Flannery, who is in charge of diocesan programs for victims. Other Oakland programs that have evolved from this cooperation include support groups, workshops, retreats and personal counseling by qualified professionals.

We continue to offer therapy, even though people are litigating against us, said Sister Flannery.

Several victims said that the smaller, private therapy programs aimed at easing the trauma are more important than the highly publicized healing liturgies. Healing services are like a ribbon-cutting. More significant is the follow-up, said Alexandria Roberts, head of the San Jose chapter of Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests. Healing services become a media circus and many victims do not have the media savvy to handle this, she said.

For Sister Ellen Finn, O.P., associate executive director for the Diocese of Brooklyn, a lot is about opening doors and making people feel welcome. She is developing healing teams of priests, religious and lay people who can work one-on-one and in groups with victims and their families. Sometimes the families need just as much care as the victims, she said.

Sister Finn’s goal is to have a healing team in each of the diocese’s four vicariates, and use them as the outreach to parishes affected by clergy sex abuse. The diocese is working with Safe Horizons, an independent organization that specializes in trauma counseling, to set up programs. Victims who are not in a professionally qualified therapeutic program are referred to Safe Horizons, said Sister Finn.

The diocese also provides victims with a list of spiritual directors trained in dealing with people traumatized by sex abuse. Many victims have a strong belief in God, and the [church] institution got in the way, said Sister Finn. They are longing for something that has been taken away from them. A major task is to get victims to see that not faith, but the institution has hurt them, she said.

Ms. Elordi of the Archdiocese of San Francisco said that when the sexual abuse occurred, part of the trauma was that priests surrounded the abuse with spiritual issues and threatened the children with a spiritual punishment, like going to hell if they told anyone what happened. In general, developing outreach programs requires creativity and patience, said Elordi. In cooperation with victims, she has held a writing workshop. Expressing feelings on paper through a diary, essays and poetry is a therapeutic way of easing emotional pain, said Elordi.

Elordi is also working with victims to develop an artistic program, in which victims with musical and writing talents would go to parishes to play music composed by victims and read their own poetry. We want people to see survivors more as persons who have done a lot to overcome their problems, she said.

Through such efforts, the church in the United States is taking steps to help Catholics find some healing and hope, enabling them to begin to move past the worst scandal ever to face the American church.