Editor's Note: This essay was originally published in America in 2009.

As It is now 50 years since Pope John XXIII surprised the world by announcing his intention to convoke an ecumenical council. Those of us old enough to remember it will recall the excitement the announcement generated among Catholics and in the larger world. That an ecumenical council would take place was extraordinary; as Catholics count, there have been only 20 of them. Pope John gradually made his intentions for the council clear: the spiritual renewal of the church, pastoral updating (aggiornamento) and the promotion of an eventual reunion of Christians.

For any of these goals to be achieved would require change in the church: spiritual renewal would demand repentance; updating would mean abandoning attitudes, habits and institutions no longer relevant and introducing ones more appropriate to the last third of the 20th century; and promoting Christian unity would mean working to overcome alienations with centuries of inertial force behind them. Something new and different appeared on the horizon. Pope John composed a prayer that the council might be “a new Pentecost!”

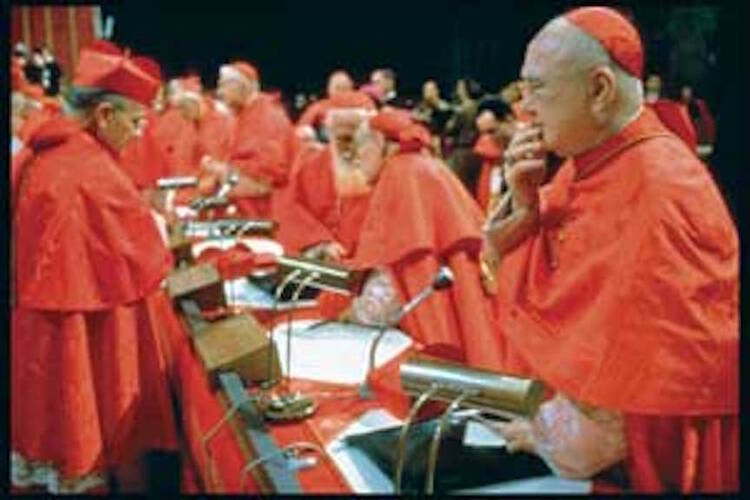

From the day it was announced (Jan. 25, 1959) to the day it ended (Dec. 8, 1965), the Second Vatican Council proved to be a particularly dramatic event, as a number of us can attest from personal experience and observation. Sixteen documents represent what that encounter of some 2,500 bishops meeting under two popes, John XXIII and Paul VI, wished to say to the church and to the world. Those texts did not drop down from heaven, but resulted from a process of conversation, confrontation, compromise and conciliation. Knowledge of this legislative history is necessary in order fully to understand and appreciate what the council wished to say—and chose not to say—in its final texts. In other words, history and hermeneutics (interpretation) go together. How they go together, however, is a key question.

The texts of Vatican II did not drop down from heaven, but resulted from a process of conversation, confrontation, compromise and conciliation.

Discontinuity or reform?

On Dec. 22, 2005, the year in which he was elected, Pope Benedict XVI, on the occasion of the traditional year-end talk to the Roman Curia, included in his review of the previous months’ events the celebration of the 40th anniversary of the close of Vatican II. The pope set out his thoughts on a correct interpretation of the council.

Before Pope Benedict’s speech, a few Italian prelates had expressed reservations about the five-volume History of Vatican II, of which Giuseppe Alberigo was the general editor and whose English edition I edited. They promoted as a counterweight to it a collection of very critical reviews entitled Il Concilio Ecumenico Vaticano II: Contrapunto per la Sua Storia. When it became known that Pope Benedict was going to address the interpretation of Vatican II, these critics anticipated that he would repudiate the view of the council thought to have guided the editors and authors of those five volumes. This is also how they interpreted the pope’s speech.

There are, however, reasons for questioning their interpretation of Pope Benedict’s remarks. There are even reasons to think that these critics have greatly oversimplified his position and the underlying issue in the interpretation of the council, which Pope John Paul II called on various occasions “an event of the utmost importance in the almost two thousand- year history of the church,” a “providential event,” “the beginning of a new era in the life of the church.”

Pope Benedict began by contrasting two ways of interpreting the council. (I take it that he did this for rhetorical reasons; there are, of course, more than two contesting interpretations of Vatican II.) The first he called the “hermeneutics of discontinuity.” In two short paragraphs he describes this approach as running the risk of positing a rupture between the preconciliar and the postconciliar church, thus ignoring the fact that the church is a single historical subject. This hermeneutic disparages the texts of the council as the result of unfortunate compromises and favors instead the elements of novelty in the documents. It may see the council along the lines of a constitutional convention that can do away with an old constitution and construct a new one, when, by contrast, the church has received an unalterable constitution from Christ himself. That is the entirety of the pope’s treatment of the “hermeneutics of discontinuity.”

One might have expected Pope Benedict to call the position he favors the “hermeneutics of continuity,” and careless commentators have used that term to describe his view. Instead, he calls it the “hermeneutics of reform.” He devotes the greater part of his talk (85 percent by word-count) to explaining what he means by the phrase. And the greater part of this explanation sets out why at the time of the council there was need for a certain measure of discontinuity. After all, if there is no discontinuity, one can hardly speak of reform.

One might have expected Pope Benedict to call the position he favors the “hermeneutics of continuity." Instead, he calls it the “hermeneutics of reform.”

Keys to Interpretation

To illustrate his interpretative matrix, Pope Benedict appeals to the two popes of the council. From John XXIII’s speech opening the council, Benedict quotes the passage that, on the one hand, gives as one purpose of the council to transmit doctrine purely and integrally and, on the other, requires that doctrine be studied and presented in a way that meets the needs of the day. Distinguishing between the substance and the expression of the faith, Pope Benedict affirmed, required both fidelity and dynamism. He then alluded to a passage in Paul VI’s closing speech that could provide some basis for proposing a hermeneutic of discontinuity, since it spoke of the alienation between church and world that had marked recent centuries. It is this consideration that guides the rest of Pope Benedict’s talk to the Curia; somewhat surprisingly in a former professor of dogmatic theology, specific doctrinal debates do not concern him in this talk.

A very rapid survey illustrates the estrangement of the church and the modern era—from the Galileo case through the Enlightenment, from the French Revolution and rise of radical liberalism to the claims of the natural sciences to be able to do without the God-hypothesis. Pope Benedict describes the church’s reaction to this under Pius IX as one of “bitter and radical condemnations” met with equally drastic rejection by representatives of the modern era. There seemed no possibility of “positive and fruitful understanding.”

Since those days, however, things have changed. In a comment that John Courtney Murray, S.J., would have appreciated, the pope says that the American political experiment demonstrated a different model than the one that emerged from the French Revolution. The natural sciences were becoming more modest in their pretensions. After the Second World War, “Catholic statesmen demonstrated that a modern secular state could exist that was not neutral regarding values but draws its life from the great ethical sources opened by Christianity,” and Catholic social doctrine offered an alternative to radical liberal and Marxist theories.

On the eve of the council, then, three “circles of questions” had formed, all of which required new thinking and definition: the relationships between faith and modern science, between the church and the modern state, and between Christianity and other religions, Judaism in particular. In each area, Pope Benedict said, “some kind of discontinuity might emerge and in fact did emerge,” a discontinuity that did not require the abandonment of traditional principles.

Pope Benedict XVI: "It is precisely in this combination of continuity and discontinuity at different levels that the very nature of true reform consists."

The pope also describes the interpretative key he thinks should be applied to Vatican II: “It is precisely in this combination of continuity and discontinuity at different levels that the very nature of true reform consists.” In explanation of this “novelty in continuity” he says that the church’s response on contingent matters must itself be contingent, even when based upon enduring principles. The principles can remain even when changes are made in the way in which they are applied. Pope Benedict’s chief example was the council’s “Declaration on Religious Freedom,” which “at once recognized and made its own an essential principle of the modern state and recovered the deepest patrimony of the church,” in full harmony with Jesus’ teaching and the church of martyrs of all ages.

If these new definitions of the relationship between the faith and “certain basic elements of modern thought” required the council to rethink and even correct earlier historical decisions, it did so to preserve and deepen the church’s inmost nature and identity.

What the pope calls “this fundamental ‘yes’ to the modern era” did not mean the end of all tensions, nor did it eliminate all dangers, and there are important respects in which the church must remain “a sign that will be contradicted” (Lk 2: 34). What the council wished to do was to “set aside oppositions that derived from error or had become superfluous in order to present to our world the demands of the Gospel in its full greatness and purity.” This was the council’s way of dealing with a difficulty in the relationship between faith and reason, stated biblically in the requirement that Christians be ready to give an answer (apo-logia) to anyone who asked them for the logos, the reason for their hope (1 Pet 3:15). This led the church into a conversation with Greek culture. And in the Middle Ages, when it appeared that faith and reason were in danger of becoming irreconcilably contradictory, it brought St. Thomas Aquinas to mediate “the new encounter between faith and Aristotelian philosophy and so put faith into a positive relationship with the form of rational argument that prevailed at the time.” It is telling that from the ensuing centuries Pope Benedict offers no examples of a similarly positive and successful achievement in what he calls “the wearying dispute between modern reason and the Christian faith.”

In the end, the clear disjunction between the two rival hermeneutical orientations with which the pope began his remarks has become rather blurred in the course of his argument. The reform Benedict sees as the heart of the council’s achievement is itself a matter of novelty in continuity, of fidelity and dynamism. It involves important elements of discontinuity. It is, of course, possible to contrast two approaches by saying of one: “You stress only continuity!” and of the other: “You stress only discontinuity!” But these positions are abstractions, and it would be difficult to find anyone who maintains either position. Perhaps the pope’s counterpoised hermeneutics represents what sociologists call “ideal types,” possibly useful tools for setting out the important questions, but not to be taken as literal descriptions of positions actually held by anyone. A hermeneutics of discontinuity need not see rupture everywhere; and a hermeneutics of reform, it turns out, acknowledges some important discontinuities.

The reform Benedict sees as the heart of the council’s achievement is itself a matter of novelty in continuity, of fidelity and dynamism.

Persuading the traditionalists

It has puzzled some observers that in order to illustrate his hermeneutics of reform, the pope used the council’s new approach to the modern age and illustrated it by the treatment of religious freedom. I think it is an indication that the pope was not addressing himself primarily, and certainly not exclusively, to the editors and authors of the History of Vatican II. When Giuseppe Alberigo wrote of the council as representing “una svolta epochale” (an epochal turning-point) he was referring in particular to the kinds of new relationships with the world that, Pope Benedict argues, the council needed to forge.

I think it is more plausible that the pope sought to persuade a different group of people, traditionalists whose rejection of the council derives in no small part from their belief that its teachings on church and state and on religious freedom represent a revolutionary discontinuity in official church doctrine. Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre, for example, had severely criticized the statement of then-Cardinal Ratzinger that "Gaudium et Spes," "Dignitatis Humanae" and "Nostra Aetate" represented “a revision of the Syllabus, a kind of counter-syllabus...an attempt at an official reconciliation with the new age inaugurated in 1789.” These texts, Ratzinger said, rightly left behind the one-sided and obsolete stances adopted under Pius IX and Pius X; it was time for the church to “relinquish many of the things that have hitherto spelled security for her and that she has taken for granted. She must demolish long-standing bastions and trust solely to the shield of faith.”

Archbishop Lefebvre regarded these comments as “liberal banalities,” indifferent to or even scorning the support the church received from the Catholic confessional state and its institutions. Union of church and state, Lefebvre argued, “is a principle of Catholic doctrine as immutable as the doctrine itself.” Lefebvre’s successor, Bernard Fellay, invoked these paragraphs of Ratzinger in a letter in 2002 as an illustration of the points of serious disagreement that remain between Rome and Ecône. His group could never accept “any heterogeneous development of doctrine,” like what the council taught about religious freedom.

Pope Benedict’s talk on the interpretation of Vatican II could be read, then, as an effort at persuading traditionalists that a distinction is legitimately made between the level of doctrine or principle and the level of concrete application and response to situations. His talk could be seen as on a par with others of his actions directed toward traditionalists, such as his clarification that the Catholic Church at the council did not surrender the claim to be the one true church and his permission to make use of the unreformed liturgy. So far, it would appear that Fellay’s group has not been persuaded. Alluding to the pope’s remarks about interpreting Vatican II, Fellay said that the council needs more than a correct hermeneutic; its teaching must be revised and corrected.

The rejection of the prepared texts at Vatican II itself brought discontinuity into the very unfolding of the council.

On continuity

The question of continuity can be put from at least three different standpoints. Doctrinally, there is clear continuity: Vatican II did not discard any dogma of the church and it did not promulgate any new dogma. The council, however, did recover important doctrines that had been relatively neglected in recent centuries, like the collegiality of bishops, the priesthood of all the baptized, the theology of the local church and the importance of Scripture. Reasserting such things meant placing other doctrines in broader and richer contexts than before. Finally, the council departed from the normal method and language of ecumenical councils like Trent and Vatican I, not least of all by following Pope John’s injunction that it offer a positive and widely accessible vision of the faith, and by abstaining from the anathemas that punctuated previous ecumenical councils.

Theologically, the council was the fruit of 20th-century movements for renewal: in biblical, patristic and medieval studies; in liturgical theology; in ecumenical conversation; in new, more positive encounters with modern philosophy; in rethinking the church-world relation; and in rethinking the role of lay people in the church. Many of these movements had fallen under some degree of official suspicion or disapproval in the decades prior to the council, an attitude reflected in the official texts prepared for Vatican II. There was real drama in the first session of the council (1962) when those texts were severely criticized for falling short of the theological and pastoral renewal already underway. The rejection of the prepared texts itself brought discontinuity into the very unfolding of the council. Much of the drama of the rest of the council revealed the difficulty of determining what sorts of texts should take the place of those spurned, of recovering “the deepest patrimony of the church,” to use Pope Benedict’s words, and of finding a language in which to express it. In all this there was considerable discontinuity.

From the standpoints of sociology and of history, one looks at the council against a broader backdrop, and one cannot limit oneself to the intentions of the popes and bishops or to the final texts. One now studies the impact of the council as experienced, as observed and as implemented. It is hard from these standpoints not to stress the discontinuity, the experience of an event that broke with routine. This is the common language used by participants and by observers at the time. The young Joseph Ratzinger’s own reflections after each session, published in English as Theological Highlights of Vatican II, are a good example. It is from this perspective that James Hitchcock calls Vatican II “the most important event within the church in the past four hundred years,” and the French historian/sociologist, Emile Poulat, points out that the Catholic Church changed more in the 10 years after Vatican II than it did in the previous 100 years. Similar positions are held by people along the whole length of the ideological spectrum. Whether they regard what happened as good or as bad, they all agree that “something happened.”

It would be helpful if such distinctions of standpoint were kept in mind. They could help scholars to identify precisely where differences in the interpretation of Vatican II really lie, and to assess whether they are really in conflict with one another. Pope Benedict’s own performance in this speech is one example of a serious effort at discernment and, were his nuanced effort imitated more widely, the debate about the council would be greatly elevated.

From the archives, F. X. Murphy reports from the Second Vatican Council.