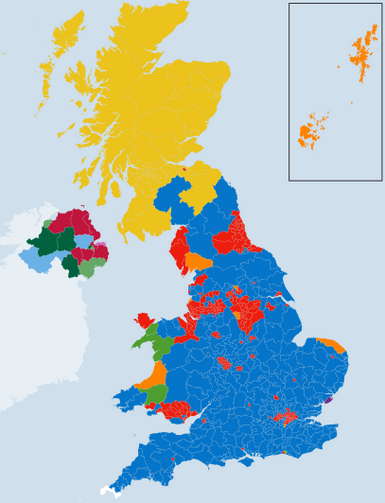

On Friday morning, the BBC was calling it a “colossal achievement” for Conservative Party leader David Cameron. With almost all the votes counted from this week’s general election in Great Britain, the Conservatives were expected to win a bare majority in the House of Commons (perhaps 327 out of 650 seats), meaning they won’t need to put together a multi-party governing coalition. But the Conservative share of the popular vote is only about 37 percent, with 31 percent for the Labour Party and nearly a third of the electorate supporting what in the United States would be called “minor” parties.

The last person to become U.S. president with such a small share of the vote was John Quincy Adams in 1824, who got 32 percent (and was awarded the presidency by the House of Representatives over Andrew Jackson, who got 38 percent). The last person to win with less than 40 percent was Abraham Lincoln in 1860, and the country fell apart over it. It’s possible the same thing will happen in Great Britain, with a pro-independence party sweeping Scotland, but in a slower and less bloody manner.

Still, some Americans may look at what happened in Britain with envy. Part of the anti-Washington fever that precedes every presidential election (see earlier post on the campaign announcements of Ben Carson, Mike Huckabee, and Carly Fiorina) is a yearning for an end to the Democratic/Republican duopoly of American politics. Among newspaper columnists, at least, the wish is for a well-mannered centrist to run for president as an independent—a Michael Bloomberg, or someone else with enough money to keep up with the Democrats and Republicans. The thinking is that only an independent candidate or a third party can transcend differences and remind Americans of their common goals.

The problem is that the “winner take all” system of American elections discourages support for independents and third parties. Pick your favorite in a multi-candidate race and you risk “wasting your vote,” or ensuring that the candidate you least like wins with less than a majority.

Great Britain has a similar “first past the post” system in which a splintered electorate could hand victory to a party that most voters oppose. (The big difference is they can’t end up with two different parties in control of the executive and legislative branches, each muttering that the other is illegitimate.) But in this week’s election, plenty of voters snubbed the two major parties. How did smaller parties win nearly 90 seats in the House of Commons despite a system that favors the Conservative and Labour parties? Not by preaching unity, but mostly by appealing to sectionalism.

The third-strongest party in the House of Commons is now the Scottish National Party (SNP), which wants Scotland to break off from Great Britain to form its own nation. The SNP is not a centrist or third-way party. It has essentially pushed Labour out of its longtime geographic base, and it seems to have reduced, not enhanced, competitiveness in Scotland’s election districts. (The Guardian says Scotland is now “a near one-party state,” with the SNP winning all but three of the 59 seats there.) This is similar to the history of the Bloc Québécois (BQ), which achieved near-monopoly status in the most heavily French-speaking parts of Quebec during the 1999s, when support for independence from Canada peaked. An analogy would be if Rick Perry foregoes another presidential run and instead forms a Texas independence party that wins almost every congressional seat in that state—or if Michael Bloomberg spends billions to fill the New York congressional delegation with people who don’t want to be part of the same nation as Texas.

Before the election, The New Yorker’s John Cassidy wrote on the destabilizing effects of the SNP: “If the fate of the British government hangs on the votes in the House of Commons of a party that is committed to getting out of Great Britain, English resentment toward the Scots, which is already evident, will escalate sharply. Indeed, it is not completely beyond the bounds of speculation that the English could end up declaring independence from Scotland!”

In the Washington Post, Griff Witte and Dan Balz previewed the British election with alarm: “The two-party system that dominated the 20th century has collapsed, and no one quite knows what will replace it.” They quote one political scientist who says Britons are now more likely “to vote with their hearts rather than vote for a mainstream party that approximates their views” and another who says this is a sign of a “dysfunctional electoral system.” Presumably they have little sympathy for Americans who say there’s something dysfunctional about having to vote for the lesser of two evils.

Witte and Balz were especially wary of the ultra-nationalist U.K. Independence Party (UKIP), which calls for leaving the European Union and restricting immigration, and “plays in part on resentment among English citizens toward the Scots for receiving what is considered a disproportionate share of government services.” Exit polls suggest that the UKIP will end up with only one or two seats in the House, but with a third-place showing in the national popular vote (about 13 percent), it remains a significant force in British politics. Meanwhile, the Liberal Democrats—Britain’s version of the centrist, high-minded third party dreamed of by New York Times and Washington Post columnists—fell to fifth place, with a humiliating 6 percent of the vote.

Back in the United States, there is theoretical support for ending the two-party monopoly. In a Gallup poll last September, 58 percent said “a third major party is needed,” up from 40 percent a decade ago. But a sustainable third party would have to engender strong passion to overcome the “wasted vote” problem. It could depend on voters who have no second choice, who dislike the Democrats and Republicans so intensely that they consider both to be “lesser evils.” In many parliamentary democracies, that means political parties based on ethnicity, religion, or, in the case of Scotland and Quebec, a desire for separatism.

The closest we’ve come to such a party in the U.S. is the “Dixiecrat” movement, consisting of Southerners opposed to federal civil rights legislation. That movement peaked with the presidential candidacy of Alabama Gov. George Wallace in 1968, who got 14 percent of the national vote and carried five states. Since then, there have been notable challenges to the two-party system, most notably by Ross Perot in 1992, but none have endured.

The “wasted vote” dilemma almost always dooms new parties. Scotland’s SNP has solved that problem by transcending ideological lines and bulldozing both “major” parties in a region that shows little interest in national unity. That’s not an appealing model in the U.S., still horrified by the bloodshed in its 19th-century Civil War.