As mid-semester approaches a number of articles have dealt with the scandals, shame and occasional successes in American education. Start with football. Sports Illustrated (9/15) opened a series called “The Money,” by George Dohrman and Thayer Evans, documenting the corruption in big college football, on full display at Oklahoma State. In the first paragraph an 18-year old freshman cornerback is handed $200 after a well-played first game. More is expected to come. For many top-tier players, education consists of having others do their homework for them, often in “easy A” or online courses designed not to educate them but to keep them eligible for the season.

Time magazine’s response (9/16) to this rot is a proposal to pay players salaries, even though many are already compensated with a free tuition, room and board, exercise equipment, physical therapy and academic tutors—equivalent to roughly $125,000 a year—plus, for some, publicity describing them as “heroes.”

The Atlantic (Oct,) contributes some good sense with Amanda Ripley’s “The Case Against High School Sports,” which highlights several schools that have eliminated at least football—retaining baseball, track and tennis—creating a new atmosphere of mature intellectual commitment.

The Atlantic lost me, however, with Karl Taro Greenfeld’s “My Daughter’s Homework Is Killing Me.” His 13-year-old daughter Esmee, in the eight grade at the New York City Lab Middle School for Collaborative Studies, has on average three to six hours of homework a night and never gets to bed before midnight, thus surviving the school week on six and a half hours of sleep a night. I have read a few other reports that grade school homework is overwhelming and have talked to a few older students with similar experiences.

I asked a recent Fordham graduate on our staff for her reaction to the “4 hours” ordeal. “What else would she do every evening other than homework?” she replied. In short, for serious students, studying is what evenings are for.

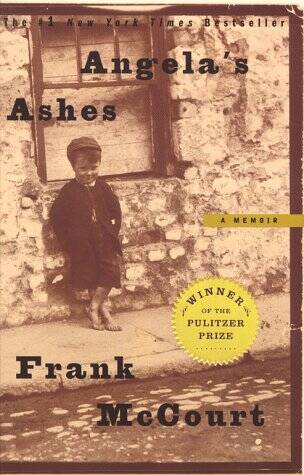

Next year Esmee will be in high school. Jesuit high schools tell their freshmen they must study at least three hours a night. The really good colleges inform their students that they should study 30 hours a week. I know that the average college student puts in maybe 10 to 12 hours a week. Where that is the case, both the students and the institutions are considered “average.” My other concern, however, is the book assigned for Esmee’s course, which, says Dad, he read along with his daughter: Frank McCourt’s Angela’s Ashes, a memoir of the author’s family struggles growing up in Ireland in the 1930’s and ‘40s.

To evaluate Dad’s homework critique I read the book and some background criticism myself. I have assigned hundreds of books in my years as a high school and university teacher, and I would never assign this one. Especially not to a 13 year-old. It won the Pulitzer Prize, but later critics called it a pack of lies (MailOnline, July 21) in the opinion of the citizens of Limerick, where the story takes place. To them it is a “misery memoir,” exaggerating a pitiable childhood dominated by a Catholic Church that threatens eternal damnation for even the most imaginary offense. McCourt relates his first communion when the host got caught in his throat and he vomited it out—thus, he says, condemning himself to eternal damnation.

Margaret Steinfels wrote in Commonweal (Nov. 1997) that when the McCourt family lived briefly in Brooklyn the mother, Angela, worked for her family. She was a formidable “take charge” woman, not the pitiful wreck smoking cigarettes by the fireplace while the father disappeared and got drunk and her family starved. And how much should we believe of Francis’ account of his youth, which includes far too much information on his various sexual escapades.

When I think of all the books that eighth grade teachers can assign, from David Copperfield to The Other America, I wonder why this one topped the teacher’s list and what the student’s father thought of the whole thing.

I recommend the Wall Street Journal’s “Review” section (Sept. 28) where Joanne Lipman demonstrates that “Why Tough Teachers Get Good Results.” She introduces her old orchestra conductor, Jerry Kupchynsky, a fierce Ukrainian immigrant, who would yell at the violin section “Who eez deaf in first violins!?” and make them rehearse “until their fingers almost bled.” But his students revered him and went on to successful careers thanking him. Rather than wring our hands about Asia and Finland roaring ahead of us in education, we should follow the most basic educational rules: “strict discipline and unyielding demands… It works.” Lipman’s eight rules include: strict is better than nice, creativity can be learned, praise makes you weak and stress makes you strong.

Sounds brutal, but Ms Lipman went on to perform in a symphony orchestra, edit the Wall Street Journal and write a book about her teacher. Maybe she got a good education. Esmee, take note.