Early in May each year Kalamazoo in Michigan hosts the world’s largest congress on the Middle Ages. This year the 49th International Congress on Medieval Studies was duly held there at Western Michigan University, the longstanding venue, from May 8 to 11. I last attended this remarkable celebration in 1993 and filed a report which appeared later that year in America (10/2/1993). What are the developments since then or has continuity prevailed?

Weather-wise the season again proved perfect with warm days to blend with the university’s scenic campus. In terms of numbers, too, there has been continuity or even some further growth. My report in 1993 said 2,700 participants; this year a figure of some 3,000 was given. This makes Kalamazoo the largest congress in the world devoted to the Middle Ages. The second largest, the “International Medieval Congress” at Leeds in England, in August, which I remember being planned by participants at Kalamazoo in 1993, numbered 1,800 participants last year.

Kalamazoo has maintained its international character. I was glad to meet at least 50 participants from my own country Britain as well as scholars from many of the countries which are represented at the Gregorian University in Rome where I now teach. In comparison with Britain, moreover, the prices of accommodation and meals were modest: there seemed to be real effort to keep costs affordable.

The range of contributions was astonishing. Altogether 556 sessions were listed, each normally with three presentations during the 90 minutes. Thus over half the participants gave a paper and time was allowed for discussion during each session. Kalamazoo remains determinedly democratic and participatory. Presentations by lecturers and professors as well as by graduate students guaranteed wide coverage in terms of outlook, which was enriched by the international provenance of the participants. Occasionally one wondered whether there was more imagination than history.

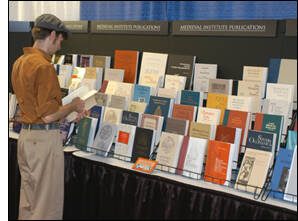

The presentations, or short lectures, formed the core of the conference. Usually some 30 sessions were being conducted simultaneously, so selection was required. The program was set out clearly in the booklet sent to participants beforehand. But there was much more besides the lectures. Notable features were medieval meals and dances. Many of the 200 or so institutions and societies listed in the booklet as sponsoring organizations held receptions for their members and visitors—another opportunity for exchange. Very remarkable and appreciated were some 70 stalls provided by publishing houses and bookshops, which were conveniently located in a series of interconnected rooms. Browsing through the offerings was an ideal way of keeping up with recent literature as well as meeting friends and colleagues.

Why does the world’s largest and most famous congress on the Middle Ages take place in a country which lies outside western Europe and which entered recorded history, for the most part, at a later date? My 1993 article, entitled “Do North Americans understand the Middle Ages better than Europeans?” sought to respond to this question. It argued that while most of the surviving evidence about the Middle Ages—churches and other buildings, the literature, etc.—comes from western Europe, so there is an appearance of familiarity, nevertheless Europe has become so secularized that it has largely lost an inner familiarity with the minds and hearts of medieval people. By contrast, North Americans are collectively more religious than Europeans and they are, for the most part, descendants of Europeans. As a result, they have retained an inner sensitivity to the mainsprings of medieval Christendom that has largely vanished in Europe.

However, this line of argument pleased few. European readers were offended with the conclusion that they had lost contact with their ancestors, North Americans by the suggestion that they were backward-looking medievals. But I would stand by the thesis and consider familiarity with the medieval genius to be a compliment rather than an insult.

How much has Kalamazoo changed during the last 20 years? Medieval church history had ceased to be largely the preserve of Catholic clergy long before 1993. Since that date the trend towards lay and non-Christian scholars has accelerated. In many ways this trend is beneficial. The danger had been of an over-emphasis on institutional and clerical aspects of the church, and not enough on popular religion and the laity. This imbalance has been corrected. Maybe the peril now is that way-out interests or mere fantasy are put center stage. But the positives are far greater than the perils. Christians can celebrate their medieval heritage, while being aware of its shortcomings, and rejoice that many other people find it such a fascinating and helpful wellspring.

Norman Tanner, S.J., teaches church history at the Gregorian University in Rome. His most recent book has just been reissued in paperback, New Short History of the Catholic Church (Bloomsbury, 2011 / pbk. 2014).