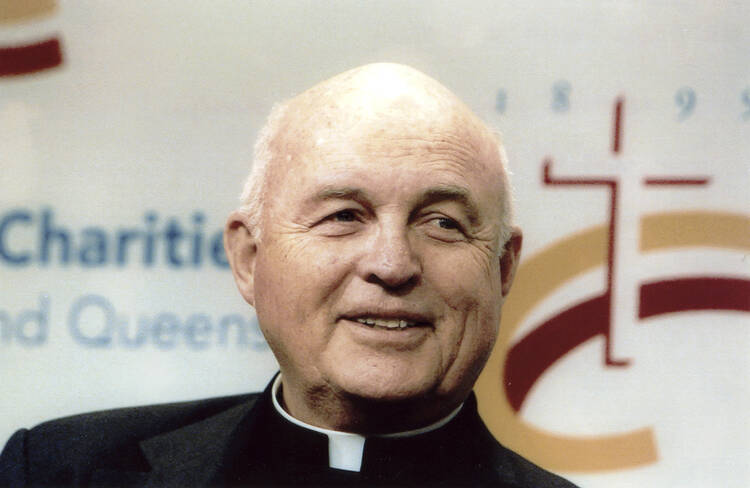

Yesterday I made my way to St Ephrem’s Church Brooklyn, New York for the funeral of Bishop Joseph Sullivan. This is the parish where Joe was baptized, educated ( “he had mostly A’s, but only a C+ in conduct” ), celebrated his first Mass as a priest and bishop, and where we gathered to say goodbye and celebrate his life. And what a life it was…

The mass led by Bishop Nicholas DiMarzio and the homily by Joe’s good friend Msgr. Joe Nagle lifted up his many gifts and accomplishment... in Catholic Charities, low income housing and healthcare; in advocacy for the poor and vulnerable in society and for gay men and lesbians in the church. (These are detailed in a number of impressive obituaries and tributes in the New York Times, National Catholic Reporter and other places.) At the funeral, we heard about his big hands and bigger heart, his great voice and quick wit, his brilliance and street smarts. The metaphor of the day was a “bridge”… from the Brooklyn bridge on his Episcopal coat of arms to the bridges he built between church and public life; rich, poor and middle class; lay, religious and clergy; pro-life and social justice; Black, white and Hispanic. He played a unique role in connecting the Bishops’ Conference to Catholic Charities and Catholic Health Care. Joe built bridges because he believed we were sisters and brothers and better together than apart.

Bishop Dimarzio rightly called Bishop Sullivan “a churchman.” He was a product of a loving Catholic family of eleven kids and an active parish and Catholic school, a priest and bishop formed by the Second Vatican Council and Catholic Social Teaching, a loyal son of the church who loved it so much he would challenge it when it fell short of the Gospel. He was also a New Yorker, a proud product of Brooklyn, fast talking, deep accent, brash demeanor and love of the city. Several people have said when Bishop Sullivan spoke at the USCCB, people listened. He was an expert without arrogance. What they fail to mention is that sometimes his speed and accent made it difficult to understand him and there was an occasional request, only half in jest, for translation of what he had just said. They didn’t always agree, but Bishop Sullivan had unique credibility among his brother bishops.

Yesterday was personal for me. Bishop Sullivan was a great leader in the bishops’ conference I served for two decades. I got to know him as chairman and almost permanent member of the Domestic Policy Committee. We went to Capitol Hill and many other places together to advocate for human life and dignity, for greater justice and peace. Joe was a tremendous friend, mentor and ally. I remember his great integrity and willingness to say the hard things in challenging situations, but most of all I remember his humanity, humor and love of his priesthood and life. Our mutual friend, Harry Fagan, used to say “no one likes a grim do-gooder.” Joe Sullivan was the antithesis of the grim do-gooder. He was a tremendous singer and storyteller. He was a happy warrior in the cause of social justice, but didn’t act like it was a war. He believed in engagement and persuasion, not lecturing and judging. He loved being a priest. He loved his work. He loved his life. He called it “heaven on the way to heaven.”

Bishop Sullivan was auxiliary bishop of Brooklyn for 33 years. The fact he never became an ordinary and led his own diocese was a shame, but seemed more disappointing for his friends than for Joe. I used to kid him by saying he was the leader of “Auxiliaries for Life” which had two meanings…auxiliaries who would never get a diocese and who fought for human life and dignity. He thought that was too informal and announced that he was a member of the “Ancient Order of Permanent Auxiliaries.” Ironically, this “auxiliary for life” had a greater influence and impact for good than many others with more stature and authority. He was a “churchman” of extraordinary humility and courage.

Bishop Sullivan lived a long and wonderful life, full of service, humor, irony and joy. I am so grateful he lived long enough to see and hear the beginnings of the leadership of Pope Francis with his simple ways and powerful words. When Pope Francis says he wants a church “of and for the poor,” he is talking about Joe Sullivan’s church. Talking to priests and bishops, Pope Francis said that the shepherds ought to be so close to their people, they have the odor of the sheep. There are no sheep in Brooklyn, but Joe carried the sounds and smells of the streets of Brooklyn with him; he had connections with ordinary people that made him that kind of pastor and shepherd. Pope Francis has said that the church “must get out of ourselves and go toward the periphery “and avoid the spiritual disease of becoming become self-referential. As Francis wrote the Argentine bishops:

A church that doesn’t get out, sooner or later, gets sick from being locked up…It’s also true that getting out in the street runs the risk of an accident, but frankly I prefer a church that has accidents a thousand times to a church that gets sick.

This is the church that Bishop Sullivan gave his life to and loved. This why we loved him and will miss him so much.

John Carr is Washington Front columnist for America and the director of the new Initiative on Catholic Social Thought and Public Life at Georgetown University. He served as director of the U. S. Catholic Bishops’ department on justice and peace for more than two decades.