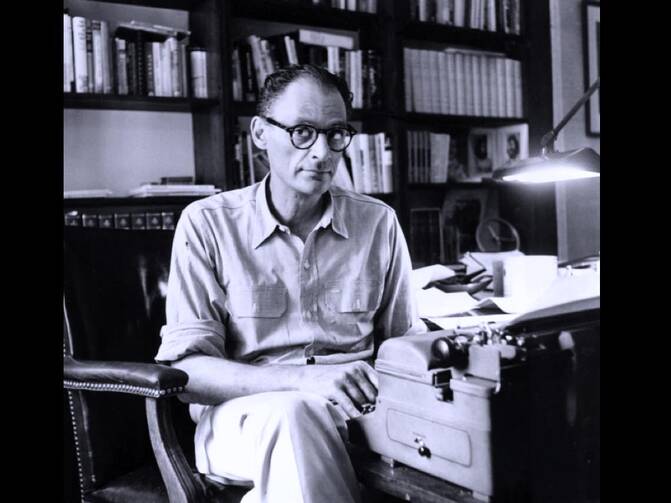

A play by Broadway’s newest wunderkind, a quickly-written (six weeks was the rumor) tale of an American traveling salesman in the last 24 hours of his life, debuted three-quarters of a century ago this year on The Great White Way. Directed by Elia Kazan and starring Lee J. Cobb and Mildred Dunnock, Arthur Miller’s “Death of a Salesman” was a huge hit by any commercial or critical standard. In 1949, it pulled off an unprecedented trifecta, winning the New York Drama Circle Critics’ Award, the Tony Award and the Pulitzer Prize for Drama. So attention must be paid!

A movie and five Broadway revivals have followed in the years since; I was lucky enough to catch the legendary 1999 Broadway redux starring Brian Dennehy and Elizabeth Franz. Cobb and Dennehy were not the only stars to play Miller’s tormented protagonist, Willy Loman: Dustin Hoffman took a stab at the role in a 1985 movie, and Broadway revivals have featured George C. Scott, Philip Seymour Hoffman and, in 2022, Wendell Pierce (the Bunk!). That last run featured an all-Black cast. Each actor brought a unique take to Willy Loman’s physically and mentally failing salesman come home to die—with Hoffman playing the role when he was only 44 (the character is 63). Various celebrities who appeared in “Salesman” in other roles over the years include John Malkovich, André De Shields, Andrew Garfield and Sharon D. Clarke.

Miller would go on to further success with plays like “The Crucible” in 1953 and “A View from the Bridge” in 1955, but “Salesman” remains his best-known work.

Born in 1915 in Harlem to Jewish parents, Miller graduated from the University of Michigan—where he wrote his first play—in 1938. Moving back to New York the next year, he worked in the Brooklyn Navy Yard and wrote radio plays on the side. In 1940, Miller married Mary Grace Slattery, with whom he had two children. They divorced in 1956. Miller’s first critical success came with 1947’s Tony Award-winning “All My Sons.”

In the early 1950s, Senator Joseph McCarthy’s communist witch-hunts inspired Miller to write “The Crucible.” The obvious parallels between the hysteria around witches in Puritan New England and the actions of McCarthy’s House Un-American Activities Committee landed Miller in trouble eventually as well: In 1956, he was subpoenaed to appear before HUAC and, when he refused to give the names of colleagues who might have communist sympathies, was found guilty of contempt of Congress and received a fine and a prison sentence (both of which were overturned on appeal shortly after).

In 1956, Miller became the hero of nerds everywhere when he won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama married Marilyn Monroe, who had only recently divorced Yankees baseball legend, Joe DiMaggio. (Norman Mailer was furious, of course.) The two remained together for five years, during which time Miller wrote the screenplay for “The Misfits,” in which Monroe starred. Monroe died in 1962, a year after their divorce. In February of that year, Miller married the photographer Inge Morath, with whom he would remain until her death in 2002.

Miller went on to write numerous other plays as well as a collection of essays on theater and an autobiography, Timebends. He served as the president of PEN International from 1965 to 1969, and became something of an elder statesman in the worlds of theater and letters in later years, garnering numerous lifetime achievement awards and being asked to comment on everything from developments in theater to Monica Lewinsky’s dress. In 1983, Miller traveled to China to produce and direct “Death of a Salesman”; a year later, a television production of “Salesman” starring Dustin Hoffman attracted more than 25 million viewers, returning the play to cultural prominence.

One critic who wasn’t a huge fan of “Salesman” from the onset was America’s Theophilus Lewis. “Since it is practically certain that Death of a Salesman will be elected best of the season, its accolade warrants a re-appraisal of its dramatic and social importance. In either department, the play is no better than second class,” Lewis wrote in his 1949 review. “In only one quality, its vigorous dialog, is Mr. Miller's play in any way distinguished. While some of the author’s admirers call the drama a criticism of our national values, it is never quite clear which popular fallacies are the targets of his censure.”

Further, Lewis asked, “Are his strictures intended to debunk the myths and vainglory that have elevated salesmanship to the status of a perverted religion, like voodooism or the nudist sect, or is the salesman a symbol of the inadequacy of material success? If the former were his intention, he has done a good job; if the latter, his treatment of the subject is superficial, faltering and rather dated.”

Later that year, Lewis weighed in on Miller again. Both “All My Sons” and “Salesman,” he argued, were “less provocative than a sermon by a country preacher.” Compared to plays like “A Doll’s House,” “John Bull’s Other Island” or “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” he wrote, “Mr. Miller’s social drama is a cap pistol popped off in a thunderstorm.”

In 2012, commenting on the Mike Nichols revival of “Salesman” starring Philip Seymour Hoffman, America’s longtime theater critic Rob Weinert-Kendt had high praise for the play:

Even though your high school English teacher said it, it is still true: Arthur Miller’s “Death of a Salesman” is a classic, even a towering one. This has as much to do with its lacerating insights into American capitalism as it is actually lived, paycheck to paycheck and bill by bill, as with its psychological acuity and near-perfect form.

Weinert-Kendt also praised the revival for its “gritty realism and surreal, only-in-the-theater lyricism” which “used to be the secret recipe that set mid-century American theater apart from its antecedents. It defined the early careers of Miller and Tennessee Williams. And though trace elements of this powerful mixture can be found in plays by Edward Albee, August Wilson, Tony Kushner and Paula Vogel, it is seldom glimpsed anymore on this scale or rendered this definitively among the frittering diversions of today’s Broadway.”

After Miller’s death in 2005, Leo O’Donovan, S.J., wrote an appreciation of him in America. “Miller was the poet of the ordinary man tested by forces beyond his control, meaning to do the right thing but often betraying his ideals,” O’Donovan wrote. “Miller was still more the poet of the individual embedded in and responsible to society.”

“If Arthur Miller’s maturity and later years remain overshadowed by his early success…the theatrical power and moral insight of his early work make him a beacon for us.”

•••

Our poetry selection for this week is “Another Doubting Sonnet,” by Renee Emerson. Readers can view all of America’s published poems here.

Also, news from the Catholic Book Club: We have a new selection! We are reading Norwegian novelist and 2023 Nobel Prize winner Jon Fosse’s multi-volume work Septology. Click here to buy the book, and click here to sign up for our Facebook discussion group.

In this space every week, America features reviews of and literary commentary on one particular writer or group of writers (both new and old; our archives span more than a century), as well as poetry and other offerings from America Media. We hope this will give us a chance to provide you with more in-depth coverage of our literary offerings. It also allows us to alert digital subscribers to some of our online content that doesn’t make it into our newsletters.

Other Catholic Book Club columns:

The spiritual depths of Toni Morrison

What’s all the fuss about Teilhard de Chardin?

Moira Walsh and the art of a brutal movie review

Who’s in hell? Hans Urs von Balthasar had thoughts.

Happy reading!

James T. Keane