A few months ago in this column, I wrote of Moira Walsh, the fierce film critic who reviewed for America from 1947 to 1974, leaving many a movie vanquished on the page. Walsh had strong opinions about the moral purpose of good cinema and was not shy about criticizing the appearance of vice on screen. She also reviewed films for many years for the Legion of Decency, a Catholic group dedicated to identifying objectionable content in movies.

When I came across her 1972 review of “Deliverance,” then, I expected a fusillade of criticism launched at the dark, violent film, written by James Dickey and based on his 1970 novel of the same name and directed by John Boorman. “I expected to hate Deliverance,” Walsh began, noting that “graphic extremes of violence” had ruined many another film, including Stanley Kubrick’s “Clockwork Orange.” (!!!) But wait:

The line between purity of intent on one hand and sensationalism and exploitation on the other never seems that clear to me. Yet I have to eat my words and tentatively accept the distinction because I found Deliverance a brilliant film.

What’s this? “All sorts of theses swirl around in the material,” she wrote. “Man against the elements, technology vs. nature, primitive vs. civilized man—but they belong there and are not forced on us in an arty or pretentious way.”

Not a bad description of James Dickey’s entire oeuvre, that.

Dickey’s poems, wrote Paul Zweig, are “like richly modulated hollers; a sort of rough, American-style bel canto advertising its freedom from the constraints of ordinary language."

The poet and novelist earned no shortage of honors and accolades throughout his career—his poetry collection Buckdancer’s Choice won the National Book Award in 1966, when he was also the United States Poet Laureate. “Deliverance” (in which he also played a small role) made him a household name, and he read a poem at Jimmy Carter’s 1977 presidential inauguration, but he always presented himself as the antithesis of pretension or even politesse. Of his appearance at Carter’s inauguration, he told reporters: “Where else in history can you find it—the President and the poet, two Jimbos from Georgia.”

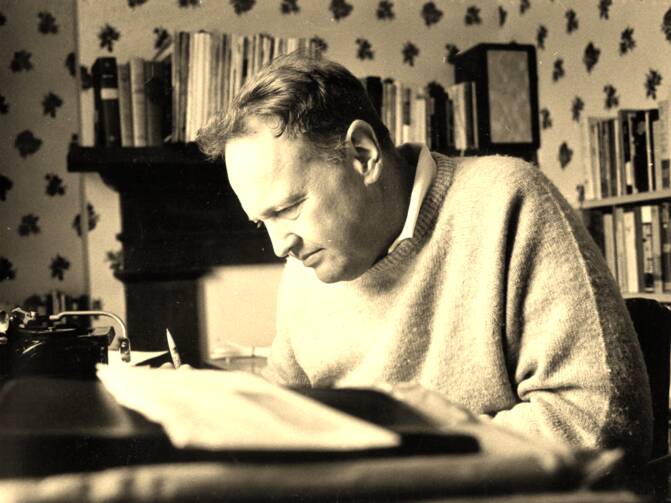

Born in 1923 in Atlanta, Ga., Dickey served in both World War II and Korea as a radar operator on P-61 fighter-bombers, an experience reflected in many of his later poems, including his famous “The Firebombing.” After numerous teaching stints (and a memorable six-year run as an advertising executive), Dickey settled in as writer-in-residence at the University of South Carolina in 1968. He published his first book, Into the Stone and Other Poems, in 1960, and followed it with more than 25 other volumes of poetry, essays and journal collections.

His public persona of fighter pilot, champion athlete and hard-drinking woodsman who wrote of “country surrealism” gave Dickey an everyman appeal, even as he was serving as a poetry consultant to the Library of Congress and corresponding with the brightest lights in the literary sky, from Ezra Pound to Robert Lowell to Denise Levertov.

Even Dickey’s darker side (“I know what the monsters know,” he once wrote in his journal), including a habit of exaggerating his own exploits, seemed to separate him from the tweed-and-elbow-patches professorial stereotypes, to say nothing of the standard image of a poet. And he enjoyed a good literary rumble: Dana Gioia recounted a less-than-edifying encounter in his literary memoir, Studying With Miss Bishop, in which an angry Dickey confronted Gioia about his negative review of Dickey’s poetry collection, Puella, leading Goia to conclude “It is often better not to meet the writers you admire.”

Dickey’s poems, wrote Paul Zweig in a 1990 essay for the New York Times Book Review, are “like richly modulated hollers; a sort of rough, American-style bel canto advertising its freedom from the constraints of ordinary language. Dickey’s style is so personal, his rhythms so willfully eccentric, that the poems seem to swell up and overflow like that oldest of American art forms, the boast.”

“Dickey writes with depth and fire, leading his reader to a world beyond sense, glimpsing the ecstasy of being human.”

In a 1972 America review of Dickey’s Sorties, a collection of journal entries and essays, David R. Bishop criticized Dickey’s journals for presenting “a ragged-edged silhouette of the author” but gushed of the essays that “Dickey writes with depth and fire, leading his reader to a world beyond sense, glimpsing the ecstasy of being human.”

In a 1995 review of To The White Sea for America, George J. Searles noted that “Dickey is powerfully adept at building suspense” and created a protagonist whose “resourcefulness in the face of unsurmountable odds elicits a grudging desire to learn his eventual fate, despite our revulsion at his grisly proclivities.” While Searles was critical of Dickey’s “tough guy” persona, he praised the book’s “shimmering lyricism when the narrator rhapsodizes about the elemental beauty of nature. At those moments, Dickey the poet is much in evidence as the wording becomes quite evocative.”

James Dickey died in 1997 in South Carolina of complications from lung disease after several years of declining health. His writerly genes were passed on: His son Christopher, who died in 2020, was a renowned foreign correspondent and memoirist, and his daughter Bronwen (a longtime friend with whom I attended graduate school) is a contributing editor at The Oxford American and the author of Pit Bull: The Battle over an American Icon.

The New York Times suggested in Dickey’s obituary that while “Deliverance” had brought the “bare-chested bard” the most fame, his poems about just about anything—from the Apollo 7 launch to football coaches (Esquire published his poem “For The Death of Vince Lombardi” in 1971) to backwoods archery—were his most remarkable achievements. Even the odes to athletes and hillbillies and fighter pilots were also “deceptively simple metaphysical poems that search the lakes and trees and workday fragments of his experience for a clue to the meaning of existence.”

You can hear James Dickey reading some of his poems in 1960 here. You can watch him speak on Dylan Thomas and poetic originality here.

James Dickey wrote “deceptively simple metaphysical poems that search the lakes and trees and workday fragments of his experience for a clue to the meaning of existence.”

•••

Our poetry selection for this week is “Envy,” by Justin Lacour. Readers can view all of America’s published poems here.

Also, big news from the Catholic Book Club: This fall, we are reading Come Forth: The Promise of Jesus’s Greatest Miracle, by James Martin, S.J. Click here for more information or to sign up for our Facebook discussion group.

In this space every week, America features reviews of and literary commentary on one particular writer or group of writers (both new and old; our archives span more than a century), as well as poetry and other offerings from America Media. We hope this will give us a chance to provide you with more in-depth coverage of our literary offerings. It also allows us to alert digital subscribers to some of our online content that doesn’t make it into our newsletters.

Other Catholic Book Club columns:

The spiritual depths of Toni Morrison

What’s all the fuss about Teilhard de Chardin?

Moira Walsh and the art of a brutal movie review

Leonard Feeney, America’s only excommunicated literary editor (to date)

Happy reading!

James T. Keane