This essay is a Cover Story selection, a weekly feature highlighting the top picks from the editors of America Media.

I didn’t grow up knowing much about saints. In the Episcopal Church in which I was raised, my knowledge was largely formed by stained-glass windows and a hymn that declared: “One was a doctor, and one was a queen,/ And one was a shepherdess on the green:/ They were all of them saints of God, and I mean,/ God helping, to be one too.” The list of these occupations did not lead me to think that saints were the kind of people you might meet every day, despite the assurance of the closing verse that there were hundreds and thousands more where they came from: “You can meet them in school, or in lanes, or at sea/ in church, or in trains, or in shops, or at tea.”

My parish church was named after St. Alban. I don’t recall ever being told anything about St. Alban, who I figured was some sort of notable English bishop. Only much later did I learn that Alban was the first martyr of the English church, a prominent citizen who lived in Roman-occupied Britain sometime in the third century. One day he gave shelter to a priest who was fleeing persecution. Although Alban was not a Christian, he was moved by the faith of his guest, and after several days he asked to be baptized. As soldiers approached, Alban exchanged clothes with the priest and sent him on his way, so that when the soldiers arrived they seized Alban, mistaking him for the priest, and brought him before a judge. After revealing his identity and declaring himself a Christian, Alban was condemned to accept the priest’s fate—to be flogged and beheaded.

By the time I was in high school I longed to know that there were saints like that—maybe not the kind that you met in lanes or in shops or at tea, but who truly exemplified what Dietrich Bonhoeffer called “the cost of discipleship.” Then one day, while perusing the shelves of my school library, I happened upon an old edition of The Little Flowers of St. Francis, a classic collection of legends about St. Francis of Assisi and his early followers.

As I skimmed over the contents of this little book, I was captivated by the picture of a man who tried faithfully, as the author put it, to be “conformed to Christ in all the acts of his life.” I read about how Francis kissed a leper and afterward abandoned the affluent life of his parents to live in poverty and serve the sick. I read about how he tamed a savage wolf with his gentleness and how he crossed a battlefield of the Crusades to meet in friendship with the Sultan. I read about his ecstatic hymn of praise to “Brother Sun and Sister Moon.” Was a saint perhaps someone who reminded us of Jesus? Even from a distance of many centuries, I experienced a sense of what had captivated so many of Francis’ own contemporaries. His example was not simply edifying but also deeply appealing. He exuded a spirit of freedom and joy. People wanted to be near him to discover for themselves the secret of his joy.

Part of my mission is to present the saints as they really were.

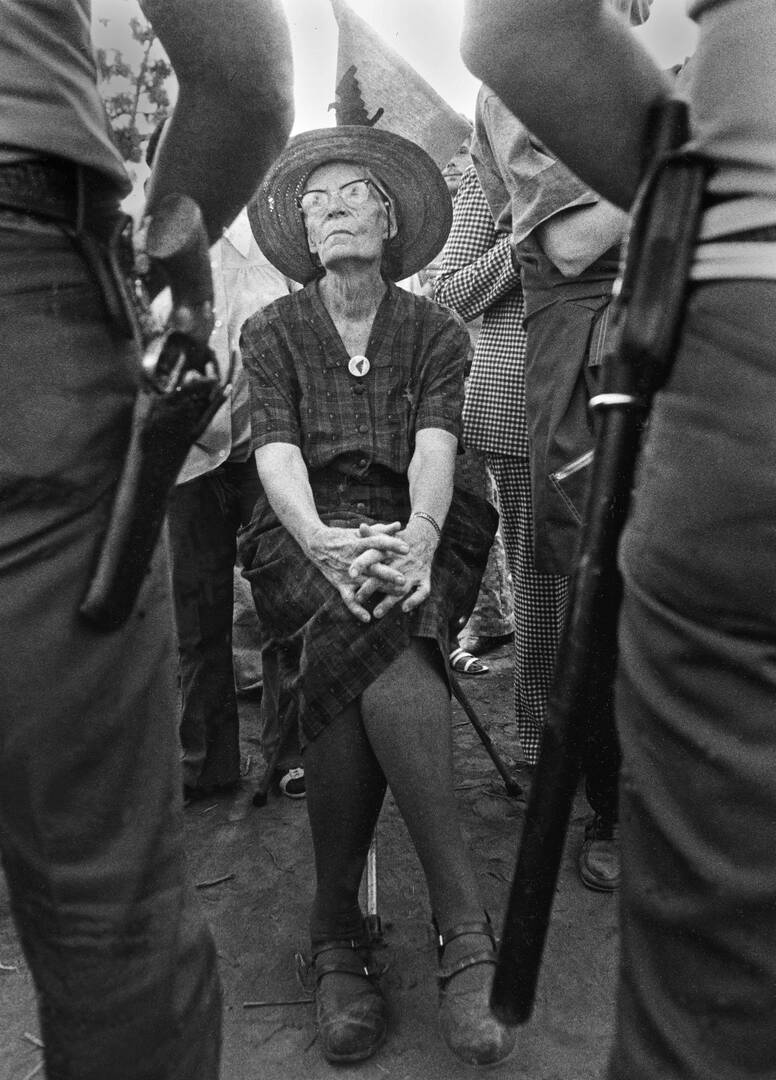

It was some years after my encounter with St. Francis’ little flowers that I saw that vision put into practice—not in a Franciscan community, but while working alongside Dorothy Day at the Catholic Worker in New York City. I had been going through some hard years of wondering what my life was for, and it felt as if the questions I was asking couldn’t find their answers in college. I had drifted away from church practice, feeling that in church I didn’t seem to come across the kind of moral witness embodied, for instance, by young people who were going to jail in protest of the Vietnam War. I had discovered Mahatma Gandhi and his philosophy of consistent nonviolence, and it was in this spirit that I found my way to the Catholic Worker at the age of 19. A famous picture of Dorothy being arrested in a protest with striking farmworkers in California struck me as an image of the Gospel in action.

Beyond that, I didn’t know much about Dorothy Day, except that her commitment to nonviolence was rooted in a wider practice of service and solidarity with the poor. I did not know the story of her conversion, or the way that her solidarity with the poor was rooted in a deeper recognition of Christ’s real presence in all who were hungry and oppressed. The Catholic Worker, the newspaper and movement she founded with Peter Maurin in 1933, was based in houses of hospitality in the slums, where lay Catholics lived in voluntary poverty among the poor they served, practicing the works of mercy—feeding the hungry, sheltering the homeless—while also witnessing for peace and promoting social justice. Here was a community where one didn’t need to be embarrassed about admiring and wanting to walk with the saints!

Soon after I arrived Dorothy asked me to serve as managing editor of The Catholic Worker newspaper—a most unlikely assignment for the next two years, though it would ultimately shape the rest of my life as a writer and editor. My five years at the Catholic Worker coincided with the last years of Dorothy Day’s life. By the time I arrived, she was already weak and bent with age, yet there was a youthfulness about her, a spirit of adventure and an instinct for the heroic that was tremendously appealing. She made you believe it was possible to start building a better world, right here where you were. She made you believe, as St. Francis did, that the Beatitudes were for living.

Dorothy died in 1980 at the age of 83, just after my return to college. By that time I had found much of what I had been seeking, and perhaps more. Among other things I had become a Catholic, inspired in large part by what I had learned about the saints, both those I read about and those I had met.

Living the Faith

There were many saints who popped up regularly in Dorothy’s conversation and writings: St. Joseph, patron of the Catholic Worker, who was himself a worker; St. Joan of Arc, a martyr of conscience; St. Benedict, the father of Western monasticism, who promoted the life of community as a path to holiness and who lauded manual labor as a form of prayer; St. Teresa of Avila, the mystic and reformer, who would raise the spirits of her sisters by dancing on the table with castanets; and her favorite, St. Thérèse of Lisieux, the Carmelite nun whose teaching on the “Little Way” showed the path to holiness that lies in all the tasks and encounters of our everyday life. And then, of course, there was “my” own St. Francis, who set out to reform the church by imitating the radical poverty and freedom of Jesus.

But anyone who spent time with Dorothy Day quickly discovered that she drew inspiration from a much wider cloud of witnesses. They included peacemakers like Gandhi, Martin Luther King, and Cesar Chavez, heroes of the labor movement, philosophers like Emmanuel Mounier, writers like Charles Péguy, Ignazio Silone, Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, and even fictional characters from their novels. She was much less interested in abstract ideas than in how such ideas were lived out, especially in practical examples of love, solidarity and community. She made little distinction between the canonized saints and other great souls.

Nevertheless, Dorothy believed it was not enough to honor or venerate such figures. All Christians were called to be saints. This didn’t mean aspiring to canonization or having a church named after them. Rather, it meant taking seriously one’s baptismal vows—responding to the call to put off the old person and put on Christ. It was a process that would occupy our entire lives and would never be fully accomplished. It was something expressed not only in great and heroic deeds but in the everyday occasions for forgiveness, patience and gratitude.

As I returned to college, I carried these lessons with me, along with a four-volume edition of Butler’sLives of the Saints. Apart from studying these volumes, my personal list of saints and witnesses continued to grow, enhanced by my studies in religion and literature, my travels in Latin America and my subsequent studies in theology.

I believe we are shaped by what we look at and what we love.

In 1987 I was invited to become the editor in chief of Orbis Books, the publishing arm of the Maryknoll Fathers and Brothers. The Orbis program at that time was especially focused on theological voices from the margins—Africa, Latin America and Asia. There I became interested in the various ways the Gospel message became incarnate in diverse cultures, in dialogue with other religious paths and in connecting faith with the urgent needs of the world. I learned about new martyrs, missionaries, theologians and spiritual explorers.

All of these interests and encounters eventually contributed to the book I published 25 years ago: All Saints: Daily Reflections on Saints, Prophets, and Witnesses for Our Time. At the time I didn’t imagine that I was writing a book that might significantly alter the way people thought about saints and the forms of holiness. Nor did I imagine that for many Christians it would become a daily devotional, read and reread in successive years.

In envisioning this book, in which I planned to combine stories of official saints with a diverse list of “prophets and witnesses for our time,” I had no thought that it would appeal beyond the select audience of those who shared my eclectic interests.

Many of my subjects, such as Camus, Kierkegaard, Thomas Merton, Simone Weil, Gandhi and Flannery O’Connor, reflected years of study and reflection. Others were new discoveries, some of them suggested by friends who were following my project: Ben Salmon, the World War I conscientious objector; Sadhu Sundar Singh, an itinerant Christian holy man in India; Walter Ciszek, the American Jesuit who spent decades as a prisoner in the Soviet Gulag; Eberhard Arnold, founder of the modern Bruderhof community; Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, the 17th-century Mexican nun and proto-feminist; Maura O’Halloran, a young Irish-American woman who achieved enlightenment as a Zen monk in Japan.

Many of my selections were inspired by a quote from Simone Weil, the French philosopher and mystic, who said that today it is not enough merely to be a saint, but we must have the saintliness required by the present moment. Of course, one’s definition of those needs is inevitably subjective. But this starting point made me alert to the many examples of saints who felt impelled by the Gospel to address a problem or challenge posed by their moment in history—a need, perhaps, recognized only by themselves. They did not simply conform themselves to some predetermined model of holiness. Often they invented and became the trailblazers for a new way of following Jesus.

Too often, as Dorothy Day observed, the lives of the saints were written “as though they are not in this world.” She continued, “We have seldom been given the saints as they really were.”

In reading the life of Dorothy Day, I was struck by the long journey that led to her own vocation in the Catholic Worker. As a child she had been attracted by the stories of the saints and their heroic service of the poor and the sick. But where, she asked, were the saints to change the social order? “Not just to bind up the wounds of the slaves but to do away with slavery?” In effect, she perceived the need for a different kind of saint, and her vocation came about in response to that call.

A Saint-Watcher

Over time I settled on the term saint-watcher for my occupation. It seemed like a friendlier word than hagiographer for someone who writes about holy lives. It also made me sound as if I was out and about, and not simply poring over archival records. The word hagiography, after all, has fallen into disrepute. It has become associated with a particularly saccharine, credulous and pious style of writing. Too often, as Dorothy Day observed, the lives of the saints were written “as though they are not in this world.” She continued, “We have seldom been given the saints as they really were.”

Perhaps that is part of my mission: to present the saints as they really were. And perhaps also to enlarge our understanding of what holiness means. And the process continues: For over 12 years, I have contributed a daily column called “Blessed Among Us” to the devotional “Give Us This Day.” In more than 1,200 columns, I have reflected on both traditional and non-traditional saints, as well as my own version of breaking news around canonizations or the passing of contemporary witnesses.

Jesus never outlined the criteria for canonization. But he enumerated a list of those who were “blessed”: the poor in spirit, the merciful, the pure of heart, the peacemakers. These are not exactly the traditional criteria for naming saints. Yet it is possible to identify these qualities not only in great figures like Mother Teresa, or Óscar Romero, but in people of our own acquaintance. Perhaps, as Pope Francis writes, they are among “our mothers, grandmothers, or other loved ones. Their lives may not always have been perfect, yet amid their faults and failings they kept moving forward and proved pleasing to the Lord.”

Above all, I am interested in the living Gospel that is written in the lives of those who have walked the path of holiness. I like that phrase—“walking the path of holiness.” When we speak of “saints” we tend to think of a finished product. But while we live we are never finished. In the case of the saints, their holiness was expressed in the whole course of living—in their quest for their vocation; in how they responded to the challenges of their moment in history; in their encounters with other people; in how they confronted obstacles, disappointments, temptations and suffering; in how they persisted up to the end. That is what it means to walk the path of holiness. And when we speak of saints in that way, it helps us recognize the lines of continuity with all who aspire to walk that path, rather than simply the gulf that separates us from their storied achievements.

In reflecting on the stories of saints, I was struck by how often a critical turning point in their lives came through their encounter with another saint.

At the end of the day, the object is not to be canonized, to be called a saint. The object is to be a whole, integrated and happy person in the best sense of someone whose life is aligned with the deepest purpose for their existence. And recognizing and honoring those qualities in other people is one of the ways that opens up our own path.

In the famous interview published in America in 2013, Pope Francis distinguished between a “lab,” or laboratory, faith and what he calls a “journey faith.” In a lab faith, everything is clear-cut and certain; all the answers are known in advance. But in a journey faith we discover God along the way; the truth emerges through experience. This is a faith that is open to the experience of doubt and uncertainty, and is always open to ongoing conversion. Francis said: “Our life is not given to us like an opera libretto, in which all is written down; but it means going, walking, doing, searching, seeing…. God is encountered walking along the path.”

St. Augustine, in his Confessions, was probably the first Christian who looked at his own life story as a spiritual text. In recounting this story, he described his restless search and his own failures and sins, which were as much a part of the story as his eventual conversion. In the end, he saw it all as a story of grace. God was present in his life, hovering over him, even in those times when the thought of God was far from him.

Dorothy Day was another who looked at her life this way. In her memoir, The Long Loneliness, she described many intimations of faith and the example of various Catholics who pointed toward her eventual conversion. But she gave equal credit to her experiences in the radical movement, the example of those who dedicated themselves to the poor, even when they were not consciously motivated by faith. She gave credit as well to her own experiences of failure and confusion, experiences of both grief and joy, and ultimately the experience of loving a man and giving birth to a daughter, which prompted her decision to become a Catholic, even though this meant separation from the father of her child, who would not agree to marriage. God, she believed, was present in the whole story. That is what a journey faith is about.

Shaped by What We Love

So why do I write about saints?

I believe we are shaped by what we look at and what we love. It makes a difference if we look at stories that elevate our spirits, empower our consciences, and open our hearts to new possibilities of human living. So often we give our attention to things that do the opposite.

My father would not call himself a “person of faith,” though no doubt he is a “person of hope.”

In reflecting on the stories of saints, I was struck by how often a critical turning point in their lives came through their encounter with another saint. Sometimes that was a personal encounter, but often it came through reading a story.

I think of all those young men and women in Assisi who were captivated by the example of St. Francis, and who abandoned their privileged lives to join him in poverty and joy. Later, that same effect came from stories about St. Francis and his followers—like those in The Little Flowers of St. Francis. As they began to circulate, Franciscan fever swept through Europe like a pandemic. That same power may lie hidden on countless school library shelves, awaiting rediscovery.

St. Ignatius of Loyola, founder of the Jesuits, traced his conversion to reading about the saints. He was a vain soldier and courtier, recovering in his castle from a war injury, when he found himself with nothing to read but a book of lives of the saints. At first he found them boring—compared with the tales of courtly valor he preferred. But gradually, as he read these stories, he found his heart strangely stirred. For the first time he recognized a different kind of valor, and the question began to arise: “What if I were to live like St. Francis, or like St. Dominic?”

It was thus for the saints. It was thus for me.

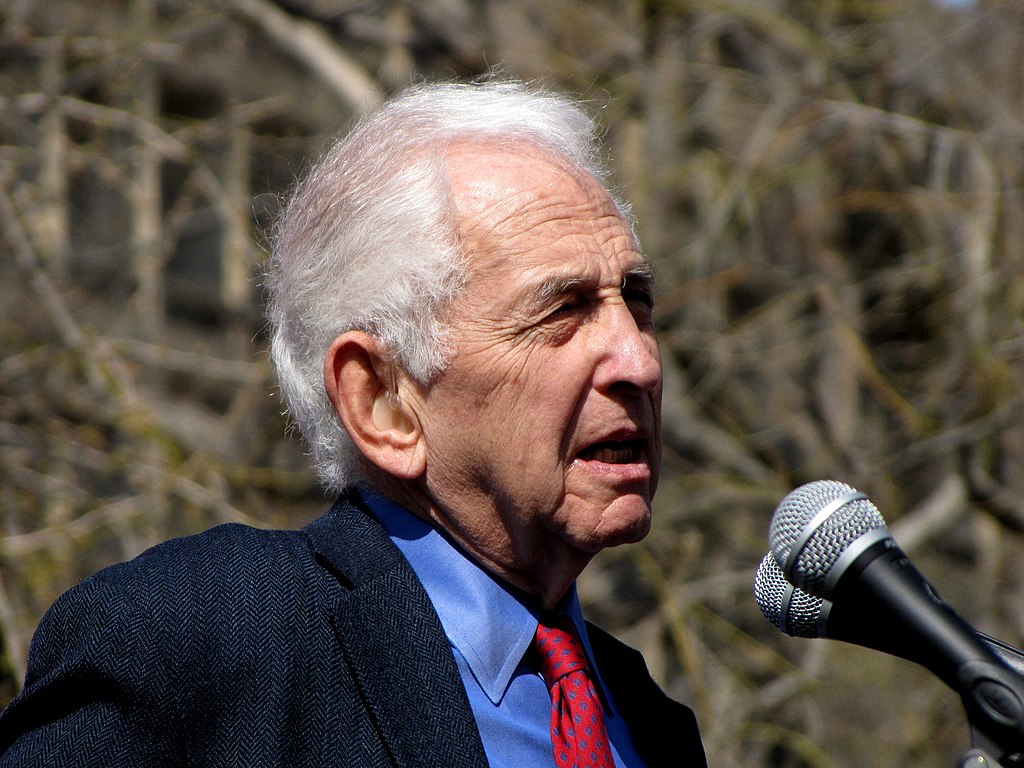

My life has been deeply shaped by the respective influences of my mother, who raised me and saw to my regular attendance at St. Alban’s Episcopal Church, and my father, Daniel Ellsberg, a former government defense analyst who would achieve fame in 1971 for releasing the Pentagon Papers to the press. [Editor’s note: Daniel Ellsberg died on June 16, 2023, from pancreatic cancer.] It was in 1969 that he first began copying this top secret history of the Vietnam War, and on a couple of occasions, enlisting the assistance of me and my younger sister. Our roles (at 13 and 10) were limited and largely symbolic. But with the expectation that he might go to prison for the rest of his life, he wanted his children to see firsthand what it looked like to take a risk on behalf of peace, truth and the greater good. In fact, when he was eventually arrested, he faced 115 years in prison.

This was part of the background of my early years, though thankfully the charges were dismissed in 1973 upon the disclosure of illegal actions by the government. The president’s efforts to conceal those actions, which came to light as a result of the Watergate investigation, resulted in the resignation of the president and the end of the Vietnam War.

Many people have been inspired by my father’s example and by his subsequent lifetime of work in the cause of peace. But I know that his action was inspired by the example of others, particularly young men who were risking their freedom by their conscientious refusal to cooperate with the draft. They had no expectation that their individual actions would change history. They did not have access to classified documents. But they did what they could. It was after listening to one particular young man calmly announce at a conference that he was about to go to prison that my father asked himself, “What could I do to help end the war if I was willing to go to prison?” His subsequent life was an answer to that question.

No doubt my father’s example had a great deal to do with my decision to leave college and go to the Catholic Worker, and thus with everything that followed. He inspired me to seek my own path, to find my own way of trying to make my life cohere with the principles I believed in. But it also led to my calling to remember and share the stories of witnesses throughout history who offered a heroic example of faith, hope and love in action.

My father would not call himself a “person of faith,” though no doubt he is a “person of hope.” In that spirit he has dedicated his life to the cause of preserving the planet from the perils of nuclear war. He does not regard hope as an expectation that all will turn out well. He regards it as a way of acting. “I choose to act as if we had a choice to change the world for the better, and avoid catastrophe.” He does not recognize himself in the company of many figures in All Saints. But there is no doubting his influence on the path that led me to write it and other books.

As I write, my father is dying of pancreatic cancer. Though not a “person of faith,” he is among those heroes whom Camus honored, those who, without the consolation of belief in an afterlife, still committed themselves to join with others in the struggle for life and against the forces of death. Thus, he has fulfilled the calling that Camus assigned to the Christians of his time: “to speak out clearly and pay up personally.”

I have seen and felt the impact of living witness—how one lamp lights another. Dorothy Day’s life was built on this conviction: the power of our small gestures, the protests, the acts of charity, which, even if no more than a pebble dropped in a pond, might send forth ripples that could encircle the globe. As she wrote, “We must lay one brick at a time, take one step at a time; we can be responsible only for the action of the present moment, but we can beg for an increase of love in our hearts that will vitalize and transform all our individual actions, and know that God will take them and multiply them, as Jesus multiplied the loaves and fishes.”

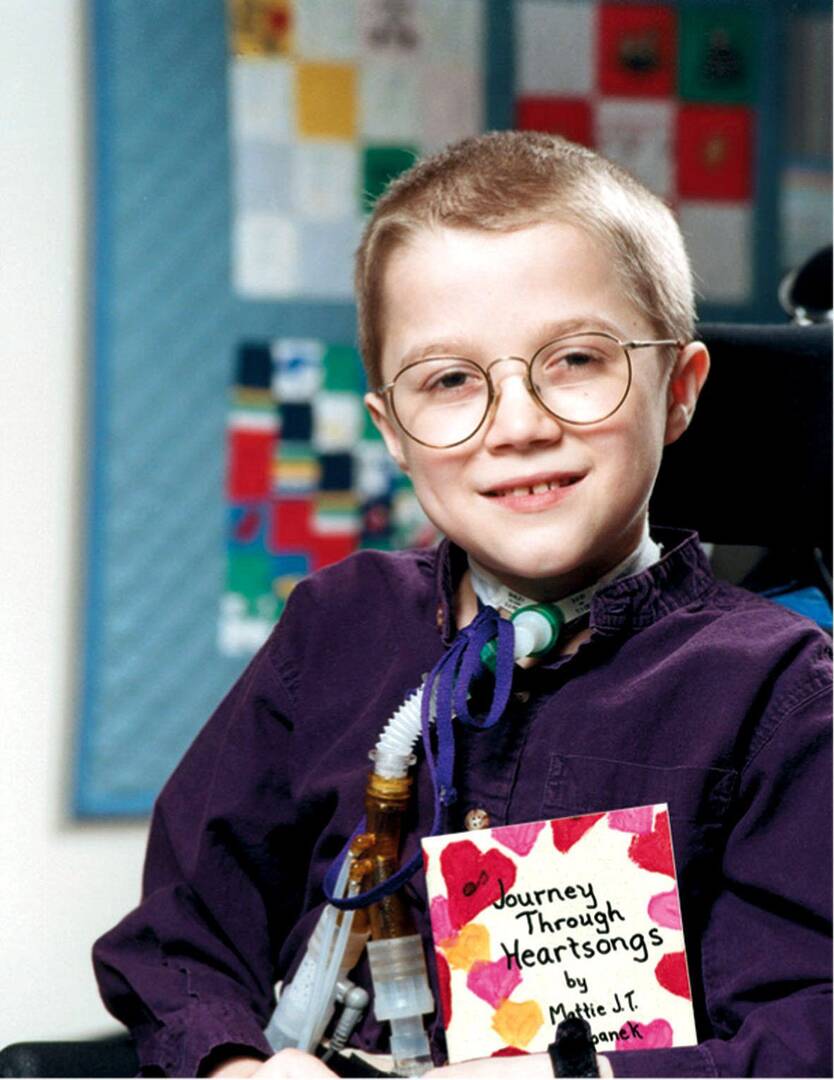

One of my recent reflections for “Give Us This Day” was about Mattie Stepanek, who died in 2004 at the age of 13 from a hereditary disease. He was conscious all his life that he was facing a young death, yet his emphasis was on living. In his short, grace-filled life, he became an ambassador for peace, publishing best-selling books of poetry, befriending Jimmy Carter (who gave the eulogy at his funeral), teaching religious education classes in his parish, and touching countless people with his remarkable witness to the gift of life. I noted that a guild is currently promoting his cause for canonization.

Afterward I received a message from his mother, who recognized my name but couldn’t immediately place it. However, in going through a box of Mattie’s things, she suddenly remembered, and sent me a picture. It was a copy of All Saints, which she said Mattie kept checking out of the library every two weeks until he could afford to buy his own copy.

This was a new experience, but also a confirmation of why I write these reflections: So that somewhere, somebody might read these stories and imagine a different way of living, and ask themselves, “What if I should live like Mattie Stepanek?”