“There is no need to create another church, but to create a different church.” Pope Francis spoke these words on Oct. 9, 2021, before the formal opening of the Synod on Synodality the next day. The words were not his, Francis noted, perhaps to alleviate any alarm over what he meant: They came from True and False Reform in the Church, by Yves Congar, O.P., one of the greatest theologians of the 20th century and a major influence on almost every aspect of the church during and after the Second Vatican Council.

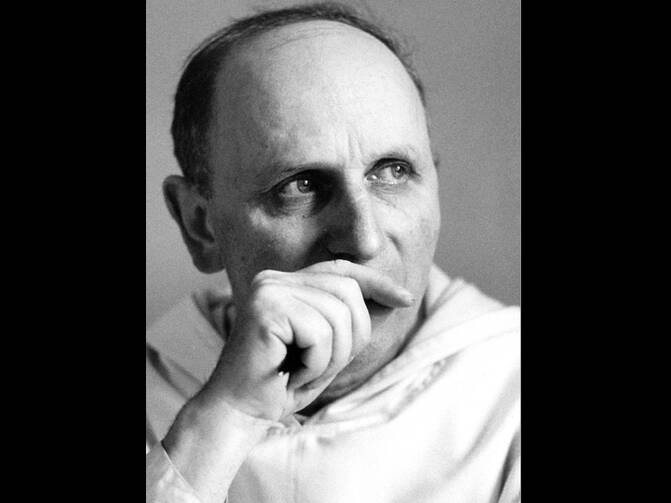

Congar was admired and read closely by every pope from John XXIII onward; he was made a cardinal of the church by John Paul II in 1994, less than a year before Congar’s death. (Here is a photo of Congar at Vatican II with a young Joseph Ratzinger, the future Pope Benedict XVI.) Avery Dulles, S.J., noted in 1995 that Pope Paul VI had wanted to make Congar a cardinal after Vatican II for his contributions to the council. In fact, Dulles wrote, “Vatican II could almost be called Congar’s council.” The great historian of that council, John W. O’Malley, S.J., agreed in 2012: “When account is taken of Congar’s writings before the council and of his influence on so many of the final documents, he must be ranked, in my opinion, as the council’s single most important theologian.”

Avery Dulles, S.J., noted in 1995 that Pope Paul VI had wanted to make Congar a cardinal after Vatican II. In fact, “Vatican II could almost be called Congar’s council."

Born in France in 1904, Congar entered the diocesan seminary after World War I; after moving to Paris in 1921, he had both Jacques Maritain and Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange as teachers. He joined the Dominicans in 1925 and was ordained in 1930, after which he began teaching theology. In 1937, he founded the influential “Unam Sanctam” book series. Some of the early volumes of the series became foundational in the movement for ressourcement, a return to the early sources of Christian theology including Scripture and the patristic scholars, and the “nouvelle théologie” school of French and German theologians.

Drafted into the French army as a chaplain during World War II, Congar was captured and spent almost the entire war in German prisons.

He returned to teaching after the war, and in 1950 he published True and False Reform in the Church; among the book’s fans was Bishop Angelo Roncalli, then the Vatican nuncio to France. Others in Rome were not so happy with Congar or what they saw as dangerous innovations in the nouvelle théologie. After the publication of the encyclical “Humani Generis” in 1950, Congar and several of his Dominican brothers were expelled from their teaching positions. The Holy Office (now the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith) also blocked the publication and translation of some of his writings. Between 1954 and 1956, Congar moved first to Jerusalem, then to Rome and then to England. “It is evident to me,” he wrote in Congar: Journal of a Theologian 1946-1956 (published posthumously), “that Rome has ever sought and seeks one thing: the affirmation of its own authority.”

“As far as I myself am concerned,” he wrote, “from the beginning of 1947 to the end of 1956 I knew nothing from [Rome] but an uninterrupted series of denunciations, warnings, restrictive or discriminatory measures and mistrustful interventions.”

The coming of Vatican II changed all that. Roncalli, now Pope John XXIII, named Congar a consultant to the preparatory commission for the council in 1960. (The Vatican being the Vatican, Congar found out in the newspaper.) Initially dismayed by the council’s sluggish beginnings, Congar eventually played a central role in writing the most important conciliar documents, including “Lumen Gentium,” “Gaudium et Spes, “Ad Gentes” and “Unitatis Redintegratio,” the last one being Vatican II’s decree on ecumenism, a particular focus of Congar’s work. That decree also stated that “every renewal of the Church essentially consists in an increase of fidelity to her own calling,” an instinct visible throughout Congar’s work before and after the Council. (Less remarkable when one considers that, in all likelihood, Congar wrote most of the decree.)

In 1967, America ran a long (and I mean long) interview with Congar by Patrick Granfield, O.S.B., a professor at the Catholic University of America. It is vintage Congar, as the theologian does not back down from his willingness to challenge the hierarchical church (and expresses some opinions that might surprise readers) but also stresses the importance of humility and commitment to the church as both an institution and a community. Even when he sounds like a radical reformer, he focuses on the roots of the Christian community rather than novelty.

“I will only say that I always did what I considered my duty, and nothing else,” Congar replied when asked about his silencing and exile before the council. “When I am convinced that something is true, then no one, not even a Pope, can make me deny it. To be sure, if the Pope or my superiors were to tell me I was mistaken, I would think seriously about it and consider their remarks in an attentive and docile way. For me truth is absolute.”

“It is evident to me,” he wrote in Congar: Journal of a Theologian 1946-1956 (published posthumously), “that Rome has ever sought and seeks one thing: the affirmation of its own authority.”

When asked if he considered himself avant-garde, however, Congar responded thus:

Absolutely not. I hope that I am open-minded and that I recognize the problems of our time. But I am a man of tradition. This does not mean I am a conservative. Tradition, as I understand it, is like the Church itself: it comes from the past but looks forward to the future and sets the stage for a new eschatology.

Tradition, he wrote, “always tries to answer current problems; it grows and renews itself. Nothing is more foolish than to think that everything has been said in the past.” But Congar also expressed his concern with those who did not learn the tradition before answering those current problems: “I am distressed when I see young clerics, sometimes even seminary professors, trying to invent a new synthesis from scratch—to meet the needs of modern man, as they say.”

After the council, Congar continued to teach, as well as publishing in areas ranging from ecumenism to ecclesiology to patristics and more, with a special focus on the theology of the Holy Spirit. He also served on the International Theological Commission from 1969 to 1985.

When Congar died in 1995, America ran two obituaries: A longer summary of his life and contributions to theology by William Henn, O.F.M.Cap., a professor of theology at the Gregorian University in Rome, and a shorter appreciation by Avery Dulles, S.J., at the time the McGinley Professor of Theology at Fordham University (he would be made a cardinal six years later).

Congar’s death, wrote Dulles, “marks the end of an era. Born in the same year as Karl Rahner, Bernard J. F. Lonergan and John Courtney Murray, he was the last of these great giants to die.”

As a theological advisor at Vatican II, Dulles noted, “Congar made direct or indirect contributions to most of the major documents, which reflect his ideas on revelation, ecclesiology, priesthood, laity, missionary activity and ecumenism.”

“Yves Congar was not only a great scholar but a churchman deeply devoted to the renewal and unity of God’s people,” Dulles added. “In his impact on official Catholic teaching and on interchurch relationships, he perhaps surpasses every other theologian of our century.”

Yves Congar: "I hope that I am open-minded and that I recognize the problems of our time. But I am a man of tradition."

•••

Our poetry selection for this week is “Carol,” by Sally Thomas. Readers can view all of America’s published poems here.

Also, big news from the Catholic Book Club: This fall, we are reading Come Forth: The Promise of Jesus’s Greatest Miracle, by James Martin, S.J. Click here to watch a livestream with Father Martin about the book or here to sign up for our Facebook discussion group.

In this space every week, America features reviews of and literary commentary on one particular writer or group of writers (both new and old; our archives span more than a century), as well as poetry and other offerings from America Media. We hope this will give us a chance to provide you with more in-depth coverage of our literary offerings. It also allows us to alert digital subscribers to some of our online content that doesn’t make it into our newsletters.

Other Catholic Book Club columns:

The spiritual depths of Toni Morrison

What’s all the fuss about Teilhard de Chardin?

Moira Walsh and the art of a brutal movie review

Leonard Feeney, America’s only excommunicated literary editor (to date)

Happy reading!

James T. Keane