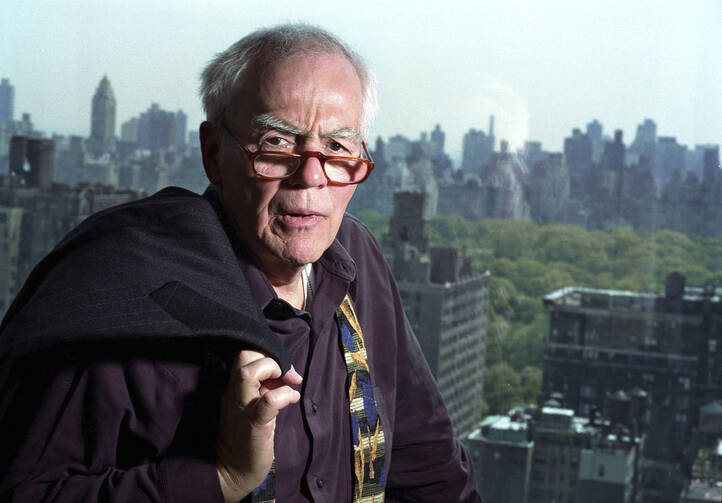

Amid a crush of urgent national and international news, an 88-year-old man died in New York on Sunday, March 18. He had been suffering from pneumonia, and he died at home. For some people, a man named Jimmy Breslin was just another elderly person passing on. But for those with a passion for the written word and the world of newspapers, he was a somebody. And Jimmy Breslin would be the first to admit it—without any false modesty.

He had a right to that boast because of what he did for a living and how he did it. He did not like being called a journalist; he thought that title was pretentious for a street reporter. This Irish-American Catholic from Queens had a great knack for chasing things, whether it was a drink (until he gave up that habit some 30 years ago), a smoke, or a story—especially if it was a story or, better yet, the story. Finding and telling stories was more to him than a job. It was his reason for being.

The man who went wherever the facts led had a life that could have been the stuff of novels (or, in his case, a newspaper serial), beginning with his Depression-era childhood with alcoholic parents, a father who left the house to buy rolls and never came back (when Jimmy was 5), and the distant mother who worked as a schoolteacher and then as an official in the New York City welfare department. Though he had a sister and was surrounded by a grandmother, aunts and uncles, what preserved him through it all was more prosaic: letters, ink and newsprint.

He had found his calling when he perused the daily newspaper, spreading it on the floor and reading the baseball scores.

He had found his calling when he perused the daily newspaper, spreading it on the floor and reading the baseball scores, imagining himself as the one who reported on it all. But he could not start with his high-school newspaper; he would later say, “I couldn’t get on it. That was only for the smart kids.” Despite that setback and the lack of a college degree (he dropped out of Long Island University after two years), he went on to pursue a doctorate in the school of life. When he turned 17, he got a job that suited him, on The Long Island Press. As he said: “I became a copy boy. Not for long. I started writing stories.”

And did he. Breslin was fortunate to be alive in a time when New York was a newspaper town. The city had 12 dailies when he started out, though the 1962-1963 newspaper strike reduced that to three: The Daily News, The New York Post and The New York Times (later joined by Newsday). Breslin wrote for almost them all, the Timesbeing the notable exception; he won a Pulitzer Prize for commentary in 1986 while writing columns for the Daily News. He also wrote scores of books on a array of topics, including baseball (Can’t Anybody Here Play This Game?, on Casey Stengel’s loveable losing team, the 1962 New York Mets), politics (When the Good Guys Finally Won, about the 1974 Nixon impeachment drama) his ancestral homeland of Ireland (World Without End, Amen, a novel about the Northern Irish “troubles”) and his Catholic faith (The Church That Forgot Christ, on the various scandals plaguing the church).

Though he wrote some novels, it was real life that interested him. The reams of his newspaper copy testified to how he took on all comers. These included Hugh Carey, to whom he gave the moniker “Society Carey” for the New York governor’s increasingly expensive tastes, and New York City Mayor John Lindsay, subject of his New York magazine piece, “Is Lindsay Too Tall To Be Mayor?” But despite his high profile, he did not find it beneath himself to take up the Sunday collection when needed in his parish church.

His most enduring fame came from his reportage on the assassination and funeral of President John F. Kennedy.

Despite his appearance of being a brawler (which he was, with his fists as well as his words), he had a joie de vivre. In 1969, he ran a losing race for New York City Council president, along with mayoral candidate Norman Mailer, on the 51st State ticket (which advocated just that for the city). He also pitched Piels beer on TV (“It’s a good drinkin’ beer!”) and played himself in the film “If Ever I See You Again,” which was cited by film critic Michael Medved in his Golden Turkey Awards book for “worst acting by a journalist.”

As has been noted in his obituaries, his most enduring fame came from his reportage on the assassination and funeral of President John F. Kennedy, which included an interview with the $3.01-an-hour gravedigger who was called to prepare a grave at Arlington National Cemetery on that dreadful November weekend in 1963. Breslin’s style—and method—of writing became the stuff of legend and journalism schools. But he was just being himself, like the boy he once was: eager to imagine the wider world, and even more eager to experience it for himself. That is something journalism schools can never teach.

Death comes to all, even to journalists. He was life’s famous “proofreader,” and he enjoyed every minute of it. One wonders how he would have covered the story of his own death. Of one thing we can be certain: he would have doggedly pursued the story and interviewed everybody worth talking to, including his own gravedigger. He wouldn’t have had it any other way, and come to think of it, it would have made great copy.