This article is excerpted from Come Forth: The Promise of Jesus's Greatest Miracle (HarperOne).

“It’s a big thing,” said Sister Vassa Larin, who holds a doctorate in liturgical studies, with an emphasis in the Byzantine Rite. She was answering my question about the importance of something I had never before heard of: Lazarus Saturday, a special feast in the Orthodox Church. In a series of emails and subsequent conversations, she carefully explained the traditions. The daughter of a Russian Orthodox priest and host of “Coffee with Sister Vassa,” an online catechetical program, she has lived in various Orthodox dioceses and monasteries and a convent in Jerusalem for two years; in addition to her studies, she was well positioned to tell me about Lazarus Saturday.

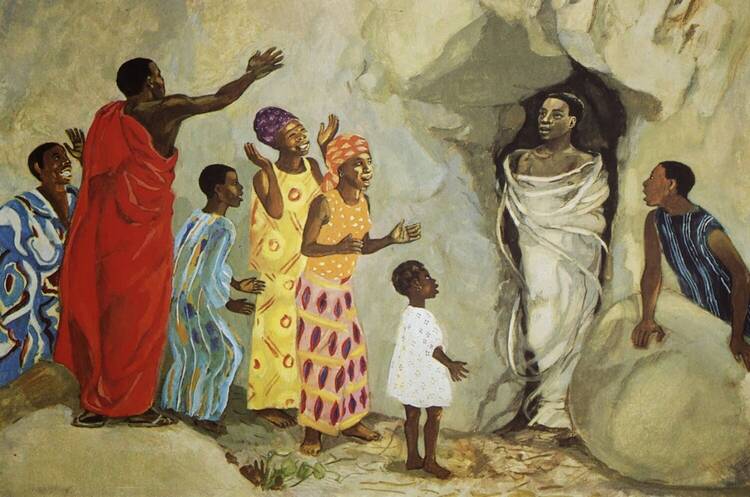

On the Sixth Saturday of Lent, also the Saturday before Palm Sunday, Orthodox churches (including the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox and Byzantine Catholic Churches) commemorate the Raising of Lazarus from the dead with a variety of fascinating customs, both cultural and liturgical. Interestingly, the hymnography (the liturgical prayers and hymns) used in the week leading up to Lazarus Saturday focus on both the Lazarus of Jesus’ parable (the poor man who had gone to the underworld) and Lazarus of Bethany being raised from the dead, the latter being seen as a kind of fulfillment of the parable.

To distinguish Lazarus of Bethany from the man in the parable, most Orthodox use the term “Four-Day-Dead Lazarus” or the “Righteous Lazarus of Four Days Dead.” (In Vienna one of the most beautiful Orthodox churches is known in the Russian community as the Chapel of the Four-Day-Dead Lazarus at the Central Cemetery, or Zentralfriedhof, where Lazarus is commemorated at every service.)

“By raising Lazarus from the dead before Your Passion,/ You confirmed the universal resurrection, O Christ God!” goes the Troparion, or main hymn, for the feast. “Like the children with palms of victory,/ We cry out to You, O Vanquisher of Death,/ Hosanna in the highest. Blessed is He that comes in the name of the Lord!” Even though it is still a week before Easter and the Passion and Death of Jesus lie ahead, the prevailing mood is one of joy.

For Orthodox Christians, said Sister Vassa, Lent ends on Lazarus Saturday. In Palestinian monasticism it was customary for the monks to spend 40 days in solitary prayer in the desert and to return to their monastery communities for the feast. Certain hymns sung only on Sundays are sung on Lazarus Saturday, and baptisms were also done on the day, though that is no longer the practice.

The liturgical color for the day, which is one of celebration, is sometimes green, but it differs from parish to parish. White, the color of resurrection, is often used, but sometimes red, said Sister Vassa. She explained that churches on Lazarus Saturday may not be “super crowded” in terms of the number of parishioners, because a few hours later the celebrations for Palm Sunday Eve take place. But, she said, most Orthodox Christians would know of this important feast.

Lenten fasting rules for the Russian Orthodox Church are somewhat relaxed for Lazarus Saturday, when caviar is allowed, along with wine and oil. On other Saturdays of Lent, wine and oil are allowed, but not caviar. Sister Vassa noted that “you can have caviar in addition to wine and oil, but no fish.” She hazarded a guess, from some online research, that this might have something to do with the imagery of the egg as a symbol of life (as in Easter eggs) but admitted that she’d never heard that explanation from any reliable source and thought it sounded “fishy.”

In terms of foodstuffs, the most charming tradition associated with Lazarus Saturday is the baking of pastries called lazarákia, or “Little Lazaruses,” which originated in either Greece or Cyprus. The connection to Cyprus makes sense since, as we will see, there is an Eastern tradition that Lazarus, after his life in the Holy Land, later became the first bishop of Kition, now Larnaca, in Cyprus, where today you can find the Cathedral of St. Lazarus.

Greek Orthodox Christians make their lazarákia out of flour, sugar, yeast, cinnamon, olive oil and cloves, but no dairy or eggs, so as to conform with the Lenten fasts. Mahleb, an aromatic spice made from the seeds of a particular cherry, is often added. Most marvelous of all, they are shaped like little Lazaruses: a tiny man bound up tightly in grave cloths, usually with whole cloves for his unblinking eyes. (See recipe, below.)

Lazarus Saturday, with its brightly colored vestments, its relaxation of fasting, and its little sweet-smelling pastries, is a joyful time. Writing about Lazarus Saturday in his book The Christian Way, the Orthodox scholar and archpriest Alexander Schmemann notes, “The joy that permeates and enlightens the service of Lazarus Saturday stresses one major theme: the forthcoming victory of Christ over Hades.”

It is a time that focuses believers on Jesus’ greatest miracle, the raising of Lazarus from the dead, which itself presages a feast of even greater joy: Easter.

Make Your Own

This recipe for lazarákia comes from my friend Jill Caldwell

Lazarákia, or “Little Lazaruses,” are small, sweet spice breads, often made by Greek Orthodox Christians on Lazarus Saturday, the Saturday that begins Holy Week. They are shaped like a man wrapped in a shroud, supposedly Saint Lazarus of Bethany, with cloves for eyes. (When I make these for my students in my religious education class, they often ask me why I am giving them mummies when it’s not Halloween.)

They contain several sweet spices and are a fasting Lenten food, meaning that they do not contain any dairy products or eggs. For that reason, they are brushed with olive oil instead of egg or butter for a gloss finish. Note, when I make them for the kids, I use raisins or currents for the eyes, because I don’t want them to bite into a clove.

Ingredients:

4 1/2 tsp. yeast

12-14 cups all purpose flour.

1 1/2 cups sugar

3 tsp. salt

2 1/2 to 3 cups lukewarm water

1/2 cup vegetable oil

1 tsp. cinnamon

1 tsp. mahlepi (mahlab) or orange rind

1/2 tsp mastiha powder or 1 tsp. vanilla extract

sesame seeds - optional

whole cloves for the eyes & mouth

olive oil for brushing (Use a good olive oil. I use Fustini’s orange flavored.)

- Preheat oven to 350 degrees.

- Dissolve yeast in 1/2 cup of the 2 1/2 to 3 cups lukewarm water. Add sugar and salt and stir well.

- Add the remaining water, oil, cinnamon, mahlepi, mastiha and 6 cups flour and stir the mixture until creamy.

- Slowly add enough of remaining flour to make a medium, not sticky dough.

- Divide dough into however many lazarákia you’d like and roll into logs. Cut slits for arms and legs. Cross arms across chest.

- Place the cloves making them look like eyes and mouth.

- Place on lightly greased cookie sheets, sprinkle with sesame seeds (optional), cover with towel and let rise for about an hour or until almost doubled in size.

- Bake lazarákia for 20-30 minutes or until golden.

- When ready, brush lazarákia with some olive oil.