Once or twice a month, Bernard McGinn receives an email from someone wanting to talk about their “special” experience. Many pose questions like, “How do I know if I’ve really had a mystical encounter with God?”

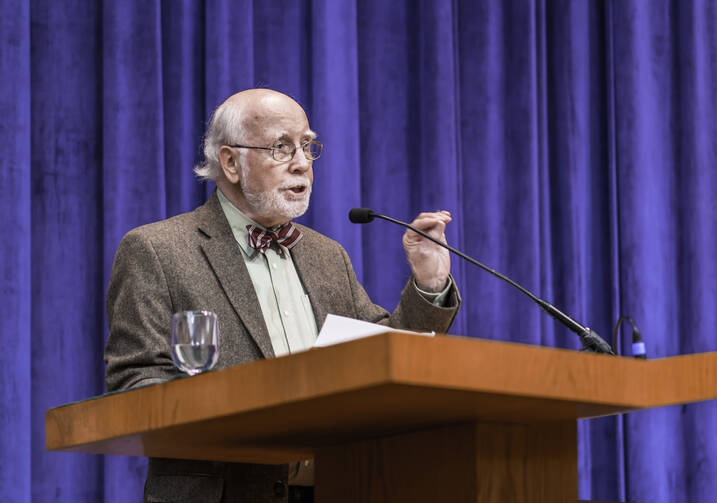

Now 86 years old, McGinn is professor emeritus at the University of Chicago Divinity School and author of The Presence of God, a nine-volume history of Christian mysticism in the West. Earlier this year, McGinn published a tenth volume, Modern Mystics: An Introduction, featuring essays on ten 19th- and 20th-century mystics, including Thomas Merton, Simone Weil, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin and Dag Hammarskjöld, the former Secretary-General of the United Nations.

McGinn seems bemused by the stream of mystics beating a path to his email inbox, as if it were a routine occupational hazard for world-renowned experts on Christian mysticism.

McGinn’s new book demystifies mysticism, showing it as a process of turning our minds toward God rather than waiting for ecstasies, raptures and revelations to descend upon us from on high.

“I say to them, there is no test of authenticity except for the effect on the person and the person’s relationships,” the theologian said in a recent interview with America. “Anybody can say that God came to them in a vision and taught them something. It’s certainly possible, but what did it do for them?”

In a way, the seekers who write to McGinn support one of his chief arguments about mysticism, one based on his reading of the historical record: The experiences are far more common than you might think.

“We need to understand that when we read the mystics it’s not an issue of ‘them’ (those wonderful mystics!) over against ‘us’ (the peons who can only admire them from afar),” McGinn writes in Modern Mystics. “If only in a limited way, we are all called to embark on the mystical path. What we need is desire.”

McGinn’s new book demystifies mysticism, showing it as a process of turning our minds toward God rather than waiting in hopeful expectation for ecstasies, raptures and revelations to descend upon us from on high.

“The heightened forms of consciousness that many mystics speak of is only a tearing away of the veils of custom, selfishness, and obtuseness that prevent most of us from beholding the profound actuality of love—love of God and love of neighbor,” he writes.

The Roman Catholic Church recognizes certain saints who have had mystical experiences, such as Teresa of Ávila, but there’s no official category for mystics.

McGinn spoke to America about his new book from his home in Chicago. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How did you first get interested in mysticism?

I read the mystics when I was training in theology. In those days—the 1950s—it was not popular. But in the late ’60s, ’70s and ’80s a growing number of students became fascinated with mystical texts, not only in Christianity but other traditions. That led me to envisage writing a history of mysticism from a theological perspective. To that point, there had been no long-term historical study of the phenomenon.

Why did students become more interested in mysticism in the 1960s? Was it a hunger for spiritual experience, the try-anything spirit of the times?

That was part of it. A lot of them, even the ones still more or less Christian, found religion over-intellectualized and over-institutionalized. And they were looking for that other dimension of religion that we call “spirituality.” That has only increased. Courses now in mysticism and spirituality are among the most widely taught.

The other connection with the 1960s is the recent renaissance of people using psychedelic drugs to catalyze mystical experiences. But your definition of mysticism goes beyond any singular experience or feeling. It’s a process.

Right. That’s important. It certainly involves feelings, but it’s not solely about states of being. Psychedelics are not a part of my research, but people ask me if it is possible to have a mystical experience on psychedelics.

And what do you say?

I say it’s certainly not impossible, but has to be studied in detail and you have to use discernment—to use a Jesuit term—the discernment of spirits. Some of these practices go back 1,000 years, and I wouldn’t exclude the role of drugs and psychedelics, but it’s certainly not the only way.

It’s hard to imagine the official Catholic Church ever sanctioning mystical experiences brought about by psychedelics.

I would tend to agree. If the special experiences are drug-based, that would likely be looked upon with suspicion. But most mystics don’t gain church approval, and many, maybe even most, have been looked upon with suspicion because they didn’t fit within the framework. The Roman Catholic Church has never officially recognized someone as a mystic. They recognize certain saints who have had mysticalexperiences, such as Teresa of Ávila, but there’s no official category for mystics.

"I compare mystics to the great figures in other human endeavors: artists, philosophers, scientists."

And yet, you quote the Jesuit theologian Karl Rahner as saying that “the devout Christian of the future will either be a ‘mystic’—one who has ‘experienced’ something—or he will cease to be anything at all.”

Yes, what Rahner meant is that a church that depends only on its institutional power is not going to grasp the future of religion: the need for a personal and experiential approach. There is a large measure of truth in that. Young people are looking for something that spiritually nourishes them, and not just an institutional structure or intellectual tradition.

For you, mysticism is not limited to singular, supernatural experiences, such as Marian apparitions or stigmata. It’s a process for which mystics prepare and after which they reshape their lives in concrete, practical ways.

Philosophers who study mysticism generally tend to concentrate on the change in consciousness or the visions. I don’t think that’s the way it happens in the lives of ordinary people, though it does happen, such as with St. Paul on the road to Damascus. But for the most part, mystical experiences, even those that are extraordinary or ecstatic, are a process built into a life that has certain kinds of prayer, reading and ascetic practices.

You identify several new themes in 20th-century mysticism, including combining action with contemplation. Is it fair to say that the popular picture of the mystic hermit in the desert is the exception and not the rule?

Thomas Merton in the 1960s was a great activist, a stance that made him somewhat unpopular among many. Monasticism has its origins in the third and fourth centuries as a withdrawal from society. The archetype is St. Anthony, who lives totally separated in the desert. But even Anthony gained fame after his time in the desert—people came out to see him. So we always see this dynamic of withdrawal and return. You see that as well in the life of St. Teresa of Ávila, who was a contemplative but also a great reformer who founded 16 nunneries and was active in the Spanish court.

The mystics you write about are complicated characters, from Simone Weil, who once identified as an anarchist, to Dag Hammarskjold, who led the United Nations.

One thing I’ve learned in studying the mystics: They tend to be extremely complex figures. I compare mystics to the great figures in other human endeavors: artists, philosophers, scientists. They may not all be intellectual geniuses, but they experiment with the limits of human nature and consciousness and introduce us to the splendid complexities of what human beings are capable of. But again, I would say that the mystical dimension in life is open to everybody.