Have you noticed over the last month or so that everyone seems to be talking about something called “Serial”? The New York Times, the Atlantic, the Guardian, the Wall Street Journal,Vulture and Slate all keep talking about it. Wednesdays on Twitter its fans come out in force, debating anxiously about the exact time on Thursday morning that the next episode will drop. The question “What if this week Serial doesn’t come until Friday?” threatens to rip the entire internet in half.

This phenomenon, believe it or not, is not a TV show, not a Netflix or Amazon program, not a movie or a book. It’s a podcast.

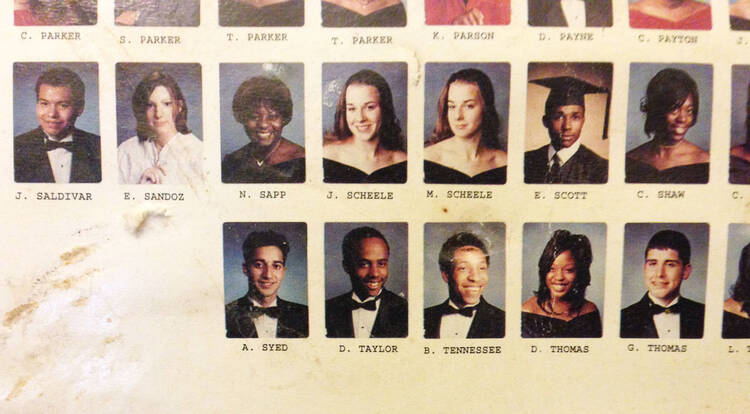

Spun off of public radio's long-running "This American Life," which tells multiple stories over the course of an hour, "Serial" (produced by WBEZ in Chicago) instead tells one story over the course of a season of 30 to 45 minute episodes. This fall the show is digging into the case of Baltimore native Adnan Syed, who as a teenager in 1999 was arrested and later convicted for the murder of his ex-girlfriend Hae Min Lee, a crime he says he did not commit.

And, as all the buzz would suggest, it’s incredibly popular; after only seven weeks over a million people now download each episode, and from all over the world.

I’m a huge fan of long form storytelling. But from the outside Serial seemed likely to be ghoulish – voyeuristic titillation under the guise of journalism, and at the expense of the real people who lived through that tragedy, most especially Ms. Lee’s family. So until the last week I’ve kept my distance.

But finally all the chatter got to me. I broke down and listened to the first episode, in which reporter and host Sarah Koenig explains how the case came to her and why she has spent the last year obsessed with it.

And then before I knew it I had not only listened to all 8 episodes but gone spelunking into many dark corners of the webternet where people are writing obsessively about the show.

Because the death of Hae Min Lee is a strange case, filled with details, contradictions, personalities (and even a theme song) that are hard to put aside. Adnan – as Koenig refers to him – had an alibi that both his lawyers and the cops strangely never pursued; though he and Hae had in fact broken up, they were still friends – a fact confirmed not only by him but by her journal. On the day before her death she had jotted down his new phone number.

And in his many conversations with Koenig Adnan is soft spoken, self-aware and more or less resigned to his fate. He didn’t bring this case to Koenig, and at times he is skeptical as to why Koenig believes in him in the first place.

His conviction hangs mostly on the testimony of another teenager who seems pretty sketchy. He was a drug dealer back then; Adnan says that they knew each other only insofar as he smoked pot sometimes with the guy. Yet this man, known on the show only as “Jay,” claims that Adnan not only confessed to him that he was planning to kill Hae, but showed him the body stuffed in a car trunk and recruited Jay to help bury her.

Jay knows so much about the day of the crime (and changes parts of the story so often) he should clearly be a suspect himself. Yet the police never searched his home or even gave him a lie detector test.

Still, important pieces of his story are confirmed by other evidence. Adnan’s phone was definitely somewhere near the burial site at the approximate time that Hae was buried. Adnan and Jay were at a friend’s house for a while after the murder, and the friend says Adnan was at one point freaking out. And there’s another call that puts Jay and Adnan together hours after the murder at a time when Adnan says he was not with Jay.

In many ways it’s all these details that Koenig provides that are so enthralling. Each one a clue, a potential key to unlocking the whole thing.

But at the same time the more Koenig has offered, the more uncomfortable I’ve gotten. Not because it seems voyeuristic or unethical (although people are clearly asking thesesortsof questions, too), but because it’s just so damn messy. The first couple episodes provide the basic facts and introduce a lot of the key players. They make you feel like you understand the landscape of this world.

But as Koenig digs deeper, talking to experts, testing theories, recreating testimony (including a surprisingly gripping reenactment of the prosecution’s sequence of events), the ground begins to vanish beneath your feet. I’ve heard so much at this point I no longer have any idea what I think about Adnan, Jay, Mr. S (another very weird character in the piece) or most anything else. I just feel lost and sad.

And if that’s how I feel after listening for a couple hours, how must Koenig feel? This show is quite a high wire act. There’s no hiding for her behind some third person omniscient perspective; each episode Koenig places her own questions and struggles very much in the center of things. Sometimes she’s flailing; but always this is her journey, and she is exposed – both to public critique and to the machinations of her subjects. I don’t know if Koenig will ever reveal how the case has affected her personally, but given the time she has put into it, I would guess it has brought her no little suffering.

Serial has become something of a Reddit phenomenon; after each episode tens of thousands of posts (yes, you read that right) go up from individuals trying to solve the crime. This is dangerous business; as The Newsroom reminded us just last Sunday, in 2013 Redditors falsely accused a man of being one of the Boston Marathon bombers, after which not only was he harassed but his sister was threatened with death.

In a recent interview with The Guardian co-producer Julie Snyder talked about her own unease with some of what people are doing with the show: “There’s something disorienting about the way the conversation about the show feels akin to the kind of discussion you might find on a subreddit about Lost.”

Jacob White, a moderator on Reddit, said in the same piece, “My worst case scenario is that a responsible party to the murder is watching the sub, gets tipped off that evidence to their guilt is surfacing, and are able to evade arrest because of us.” As it is, people discussed and/or interviewed in the podcast have found their lives and the lives of family members turned into fodder for public conversation. (A post from two weeks ago on Reddit discussed whether or not a certain person’s father might have committed the crime. That father has never even been mentioned by the podcast; but through digging, people have discovered all sorts of things about him.)

At this point the show is more than half over, and it’s still far from clear who is lying and who murdered Hae. (Even for Koenig herself that appears to be the case.) But the more I listen to the podcast and read other people’s comments, the more I think it’s not a show about clarity or solving a case. Rather it’s an encounter with the persistent existential murkiness of our human existence. What Koenig has stumbled on and shares with us is disturbing, impenetrable ambiguity.

The story of Hae Min Lee, Adnan Syed and Jayis not a religious story, not by any means. But it does seem to be a story about the fog of evil. And the deeper we push out into that, the more I recognize the need for something or someone who can light the way back to shore.