Relations between the Catholic Church and the Jewish people are, to use a biblical metaphor, like a house built on solid ground. It can endure the buffeting winds of whatever storm might tear down another house built on less secure foundations. This is because the builders have been master architects, like Pope John XXIII and Cardinal Augustin Bea, S.J., Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel and Jules Isaac.

Advances in Jewish-Catholic relations would not have happened without the vigorous leadership of Servant of God Pope John Paul II and his successor, Pope Benedict XVI. Both popes have placed fostering Jewish-Catholic relations at the top of the church’s agenda. Pope John Paul II’s historic pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 2000, during which he placed in the Western Wall an unforgettable prayer for forgiveness for the past sins of Catholics against Jews, is eloquent testimony to that. Pope Benedict XVI in the first year of his pontificate became the second pope in history to visit a synagogue (in Cologne, Germany). On Jan. 17 he visited the Synagogue of Rome, where he affirmed the enduring presence of Rome’s Jewish community as a testimony to God’s providential love. Like John Paul II, Pope Benedict XVI has regularly condemned anti-Semitism, acknowledged the profound spiritual bond between the Jewish people and the historic land of Israel and affirmed that Jewish faith and witness are internal to Christian identity.

No pope has invoked the memory of the Holocaust of the Jews under the Third Reich as often and with such eloquence as Benedict XVI. After standing in prolonged silence at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem on May 5, 2009, the pope said that the millions of Jews who lost their lives in the Shoah will never lose their names because they are forever fixed in the memory of God; they are etched on the hearts of all those “determined never to allow such an atrocity to disgrace mankind again.”

Recent Moments of Tension

In the present pontificate, there have also been occasions of tension resulting mostly from misunderstanding: for instance, the publication of the document issued by the pope motu proprio (on his own initiative) on July 7, 2007, that gave permission for a wider usage of the Roman Missal of 1962 in the celebration of Mass. This older form of the Mass contains an infamous Good Friday prayer for the conversion of Jews. The following February, Pope Benedict issued a personally revised version of the prayer that removed historic stereotypes depicting Jews as spiritually blind and needing to be delivered from darkness. This new prayer still asks that God illumine the hearts of Jews so that they may acknowledge Jesus Christ as the savior of all people.

Jewish reactions were of disappointment. Many had hoped that the pope would use the prayer from the 1970 Missal, which prays, without any explicit reference to conversion, that Jews may grow in the love of God’s name and in faithfulness to the covenant. Jewish disappointment has been mitigated by an interpretation given to the revised prayer by Cardinal Walter Kasper, president of the Pontifical Commission for Religious Relations with the Jews. The cardinal explained in an article on April 18, 2008, in L’Osservatore Romano that the prayer should be heard as an expression of eschatological confidence on the part of Christians that all Jews will be included in the final community of God’s elect at the end of time. The church respects, the cardinal asserted, Jewish covenantal life and renounces any missionary program aimed specifically at converting Jews.

Devoted to the older form of the Mass is the Priestly Society of Saint Pius X, whose founder, the late Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre, led his followers into schism in 1988 when he ordained four bishops without papal consent. Lefebvre had been a staunch critic of the Second Vatican Council, especially its teachings on religious freedom and dialogue with other religions.

Pope Benedict took the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Blessed John XXIII’s calling of the council to make a magnanimous gesture. Rather than first negotiate toward agreement on outstanding difficulties with the council and the unlawful ordinations of the four bishops by the now deceased Archbishop Lefebrve, the pope agreed to first remove the excommunications on the four bishops and then set up a dialogue. But the pope was blindsided by a development that had escaped the attention of his staff. One of the bishops, Richard Williamson, in an interview with Swedish television, conveyed his reprehensible views denying the reality and scope of the Holocaust. It had appeared at first blush that the pope had rehabilitated a Holocaust-denier who was now a functioning bishop of the Catholic Church.

The Holy See came in for an avalanche of criticism. In the following weeks, the status of Williamson and the other bishops was clarified: Though they were no longer excommunicated, they still could not lawfully exercise ministry as Catholic bishops until they had accepted the church’s teaching in its totality. The pope reaffirmed the church’s unequivocal condemnation of anti-Semitism and determination to honor the memory of the six million Jews who died in the Shoah. In a letter to the bishops of the church, he acknowledged the hard lessons learned about the need for better communication within church structures and between the church and the mass media. He also pointed out the sad irony of what had taken place: “A gesture of reconciliation with an ecclesial group engaged in a process of separation thus turned into its very antithesis: an apparent step backward with regard to all the steps of reconciliation between Christians and Jews taken since the council—steps which my own work as a theologian had sought from the beginning to take part in and support.”

The U.S. Bishops’ Note

In the United States we bishops have also learned that efforts to address internal Catholic Church problems can sometimes spill over to interreligious relationships, with harmful consequences. Last June two standing committees at the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops issued a note clarifying what we considered to be ambiguities in a Catholic-Jewish dialogue statement from 2002 entitled Reflections on Covenant and Mission. Our conference had received expressions of reservation from scholars and Catholics about some claims in Reflections. Among them was the observation that Reflections was ambiguous about the role of Jesus Christ as the unique savior of all people and that the dialogue statement seemed to question whether it is ever appropriate for Jews to become Christian.

To address the ambiguities, our doctrinal and ecumenical/interreligious committees published the note, which affirmed Catholic belief in Christ as the savior who fulfills all of God’s previous promises and covenants made with Israel and stated that Christians have a responsibility at all times to witness to Christ. Yet the seventh paragraph made use of an unfortunate expression that suggested to our Jewish partners that our dialogues with them are an occasion for inviting them to baptism and abandoning their own faith. A letter signed by a coalition of five leading Jewish organizations (addressed to Cardinal Francis George, the U.S.C.C.B. president; Cardinal William Keeler, my predecessor as moderator for Jewish affairs; and several other conference officials) contended that “once Jewish-Christian dialogue has been formally characterized as an invitation, whether explicit or implicit, to apostatize, then Jewish participation becomes untenable.”

On Oct. 6 Cardinal George and four other bishops responded to the coalition letter by announcing that the note would be revised by excising the two problematic sentences of Paragraph 7. The bishops also issued a statement of six Catholic principles for its dialogue with Jews. Among the principles is an acknowledgment that “Jewish covenantal life endures till the present day as a vital witness to God’s saving will for his people Israel and for all of humanity.” Most critical to the relationship was the assurance that the dialogue “has never been and never will be used by the Catholic Church as a means of proselytism,” nor is it “a disguised invitation to baptism.” “In sitting at the table,” the bishops said, “we expect to encounter Jews who are faithful to the Mosaic covenant, just as we insist that only Catholics committed to the teachings of the Church encounter them in our dialogues.”

In a final letter the Jewish coalition welcomed the fact that our episcopal conference not only heard the concerns of Jews, “but are making efforts to be responsive to them.” “We were deeply troubled by the original wording of this document and hope this will now put our dialogue back on a positive track,” the authors wrote.

My hope is the same. We cannot afford crises that divert our attention from other pressing issues that Jews and Catholics must face together, like the nature of the covenants God has made with his people through time. Jewish understandings must be factored into the ways in which we Christians reflect on the distinctive relationship that we believe is brought about by the life, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. Catholic theology can be enriched when Catholics and Jews together explore themes in their respective traditions. By tending to the ways in which Jews define themselves as a people of faith, we Catholics discover a valuable resource for deepening our own self-understanding as believers.

A Proposal for Dialogue

Future conversation might profitably examine the ways in which our two communities are seeking to strengthen the spiritual identities of their members in a culture marked by religious individualism. The U.S. Religious Landscape Survey, released last year by the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life, confirms the impact of both secularization and movement from one religious affiliation to another among significant portions of our society.

The Catholic Church continues to be the largest religious denomination in the United States, at around 25 percent of the population. This apparent stability obscures, however, the number of Catholics who have left the Catholic Church. Roughly 10 percent of the U.S. population, according to Pew, are former Catholics—30 million people. Where do they go? Many join other churches or affiliate with other religions. Many enter the fastest growing segment of the population examined by the Pew study: those who self-identify as “unaffiliated.”

When compared with Catholics, who retain their members at a rate of 68 percent, Jews fare better at 76 percent. But self-identification is not always a clear barometer of religious practice. What the Pew report and other studies show is something many of us in ministry and the rabbinate know intuitively: most Catholics and Jews who break allegiance to the religion of their upbringing do so as teenagers and young adults. What can be done to understand and stem this pattern? Can we learn from one another how religious identity is successfully being shaped? What are young Jews and Catholics looking for in an age of religious individualism?

These are big questions. Only brief pointers can be suggested as to how we might together engage them. First, we could examine how our communities create for young people what social theorists refer to as “third space.” If “first space” refers to the private sphere of home and family, and “second space” to the public spheres of work and commerce, then third space consists of a middle ground that combines elements of familial intimacy with communal modes of interaction. “Third space” includes associations where people form friendships and contribute to the welfare of the wider communities. These spaces are home to the relational networks or mediating structures once described by Alex de Tocqueville as salutary to American civic life.

For Jews and Catholics, religion is a given; it is inherited; we are born into it; it is part of our DNA. God chose the Jews, not the other way around. Jesus reminded his disciples, “It is not you who chose me, but I who chose you.” Catholics call this an ecclesial reality. While Jews might not use that word, they know the reality. We are Jews, we are Catholics, in the same way that we are members of a human family: belonging to a people or a church is essential for us. This has profound spiritual and theological meaning. But it is hard to explain in a culture where individual choice trumps ontological realities. The Pew research tells us that “inherited religions”—read Jews and Catholics—face a crisis in that their members do not value “received religion” in the way their grandparents did. People today want to believe but not to belong. To engage this development is a pastoral project that must unite Catholic and Jewish pastors.

My second recommendation is that we examine together the hunger for spirituality. The sociologist Robert Wuthnow not long ago compared religious behavior among Americans today with the behavior of the generation that came of age after World War II. Observant Jews and Christians are more likely to see themselves as “seekers” rather than “dwellers.” Fifty years ago young adults looked for a spiritual home where they might find a spouse and raise a family. Today many migrate from church to church, from one form of religious commitment to another in search of community (“third space”) and spiritual practices that help them experience God’s healing presence and guidance in their lives.

Young Catholics in Europe and the United States have lately shown an interest in traditional Catholic devotions like eucharistic adoration, monastic meditation and pilgrimages to holy sites. How are young Jews seeking to engage the discipline of Sabbath-observance and the study of Torah? Can we explore together these analogous patterns of spiritual hunger? Young people today say, “Feed me spiritually or I will go elsewhere to find sustenance.” As one rabbi friend observed to me: “I’m so happy to see that the ‘spirituality section’ is the fastest growing area at my local Barnes & Noble. I’m so sad to notice that there’s not a classical Jewish book among the shelves.” There is probably not a Catholic one there, either. Jewish and Catholic pastoral leaders can come together to reclaim the spirituality section from the self-help and New Age gurus and restore the enriching, ennobling, sustaining wisdom of the ages handed on in both of our spiritual traditions.

These are only two issues of many that can engage Jews and Catholics in a dialogue over the most pivotal issues of all: salvation, holiness, justice, interior peace, a purpose in life, an acceptance of God’s love, mercy and invitation to life in the fullest. We owe it to the heroes who went before us and to God’s children who come after us to keep at it with love, grit, honesty and respect, in friendship and in the shalom of God the Most High.

It was Jesus who in John's Gospel reminds all that "Salvation is from the Jews!" Thus, without Jews there is no salvation for anyone. For this reason alone an unbreakable bond needs to be acknowledged as existing between Christians (Catholics) and Jews. And lest we forget, Jews called by God to be his "Chosen" remain so. With God there is no such thing as change, or alteration. However, it must also be acknowledged as St. Paul asserts, that, we Chistians now share with Jews this "Chosenness" through Jesus.

Over millennia, however, there has been lots of nastiness on both sides, making jagged our God-initiated "Chosenness." Both Christian and Jews have sinned therein and there is much room for repentance on both sides.

But as Archbishop Dolan pointed out, Christians (Catholics) share one spiritual DNA with Jews. Indeed (isn't it true?) everytime we receive the Eucharist, this new "Manna from heaven" we acknowledge and proclaim our spiritual DNA of soul with the People of Israel. In the Eucharist, we participate in and affirmatively proclaim the sacrificed Resurrected Body and Blood of the Jewish Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world! The Resurrected Jewish Body and Blood of Christ transfuses us! Thereby and therein through our Father Abraham in Covenent,is nourished our spiritual DNA of soul, shared through our Jewish brothers and sisters. How very close we are!

Truly, as Pope Pius XI has said, "It is impossible to be Catholic and anti-semetic at the same time!" And truly as Pope John XXIII pointed out, Christian and Jews are "brothers!"(and sisters.) May the Servant of God, Venerable Pope Pius XII, who did do very much clandestinely to protect Jews from Satan's Deputy, Adolph Hitler, yet is so unjustly savaged by many pray for us all!

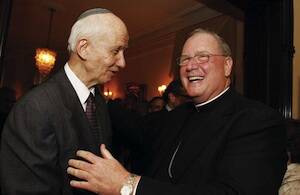

Archbishop Timothy Dolan’s article from this last issue was amply referred to in a Catholic-Jewish Dialogue yesterday in Marco Island, Florida. With about 175 people in attendance, Fr. Tim Navin, Pastor of the Catholic Church of San Marco referred to the article, especially in response to Jewish questions about the modification of the “Good Friday” prayer for Jews as well as several other issues.

While both Jews and Catholics are anxious to walk a “Shared Path,” it is incumbent upon both the Hierarchy and theologians to resolve adequately four issues:

1. Is the language found in n. 16 of Lumen Gentium that appears to supersede “nullus salus extra ecclesiam to be unquestionably affirmed or not?

2. Will the historical documents possessed by the Vatican with regard to Pope Pius XII and his assistance or lack thereof to Jews be made public? With the declaration of his “Heroic Virtue” in the recent past, it would be prudent to document such heroism with regard to Jews.

3. While the unintended consequence of the lifting of the Latae Sententiae penalties on the Society of Saint Pius X was embarrassing to the Papacy, should there be an additional gesture to our partners in dialogue regarding the affirmation that the principles of Nostra Aetate would have to be affirmed by SSPX members?

4. The rationale for the change of the prayer for Jews in the Latin Rite on Good Friday ought to be made clear; does the Church still ask Jews to apostasize?

In my opinion, there is still lack of coherence in the Church’s positions.

Dr. John T. Conroy, Jr.

Assistant Professor, Blessed Edmund Rice School for Pastoral Ministry, Diocese of Venice, FL.