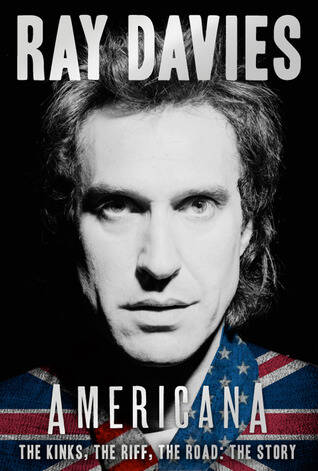

Residents of New Orleans can be forgiven if they've recently felt the ghost of Binx Bolling roaming their streets in the form of British rock royalty. Binx, the abstracted, alienated main character from Walker Percy's 1961 novel, The Moviegoer, wandered through New Orleans and its suburbs ducking into movie theaters to escape the "everydayness" of his life through celluloid fantasies. In his new memoir Americana--The Kinks, The Riff, The Road: The Story, Ray Davies is every bit a latter-day incarnation of Percy's best known creation.

Longtime fans of Davies, like myself, shouldn't be all that surprised. The Kinks frontman has always been out of step in the most compelling of ways. In the first onslaught of the Bristish invasion in the mid 1960s, the Kinks distinguished themselves with garage rock gems like "You Really Got Me," "All Day and All of the Night" and "Til the End of the Day." But Davies—like his Anglo songwriting peers Lennon/McCartney, Jagger/Richards and Pete Townshend—soon tired of the traditional pop song subjects of girls and young love.

When Bob Dylan revolutionized pop music by expanding its horizons into more complicated and socially conscious areas, his British counterparts took note and began expanding their notions of what topics rock 'n' roll was capable of taking on. A funny thing happened on the way to the revolution though. While the Beatles wrote their own ("Revolution"), the Stones sang about a "Street Fighting Man" and The Who sputtered on about "My Generation," Ray Davies wrote "The Village Green Preservation Society" in which he waxed melancholic and poetic about the loss of traditional English values and lifestyle:

We are the Village Green Preservation Society

God save Donald Duck, Vaudeville and Variety

We are the Desperate Dan Appreciation Society

God save strawberry jam and all the different varieties

Preserving the old ways from being abused

Protecting the new ways for me and for you

What more can we do...

God save the Village Green.

As the rock and roll gods were storming the castle, Davies was trying his best to make sure the civility of afternoon tea time wasn't disturbed. His songwriting was nothing short of brilliant. In the late 60s, when grand gestures and social upheaval were the norm in rock 'n' roll, Davies wrote some of the most intimately observed and poignantly crafted music ever recorded. If there is a more beautifully wrought song about two lovers than Davies' Waterloo Sunset, I've yet to hear it.

Terry meets Julie, Waterloo Station

Every Friday night

But I am so lazy, don't want to wander

I stay at home at night

But I don't feel afraid

As long as I gaze on Waterloo sunset

I am in paradise

Like much of the Davies songbook, the beauty of his melodies and tender depiction of the characters in his songs are also infused with an ache and detachment that is unmistakably all his own. That overwhelming sense of alienation and anomie soaks through every page of Americana.

Having finally conquered the American market with FM radio hits and arena tours in the 70s and 80s, Davies eventually dissolves the Kinks in the early 90s and sets about the task of discovering what the next chapter of his life/career will be. That search ultimately lands him in New Orleans where he hopes to reignite his own muse in the place where so much of the American music he loves was born. What he finds instead is the same rootlessness and disconnection that has marked his entire life. Though much of his best music has a powerful—usually British—sense of place, Davies himself is in many ways a man without a home.

If Binx finds some measure of hope and purpose in “the possibility of a search,” Davies' own search is mired in what feels like nostalgia for a time that never quite existed. It's as if he continues to feel the pain of a phantom third arm.

His abstracted journeys through the streets of New Orleans abruptly come to an end when he's shot by a mugger in early 2004. Fortunately the shot wasn't fatal, but as he recounts his healing process, I began to wish the shooting had had an even greater impact on him. Not in terms of his physical health of course but in terms of his ability to gain some insight into what is painfully obvious to his readers: the self consciousness that is so essential to his ability to write so movingly about other people's lives is also the greatest impediment to his ability to fully inhabit his own life.

In the end, the reader is left with two certainties: the great Ray Davies no longer haunts the streets of New Orleans and rock's latter-day Binx Bolling is out there somewhere on earth right now wandering the streets. Still searching and as sunken into himself as ever.