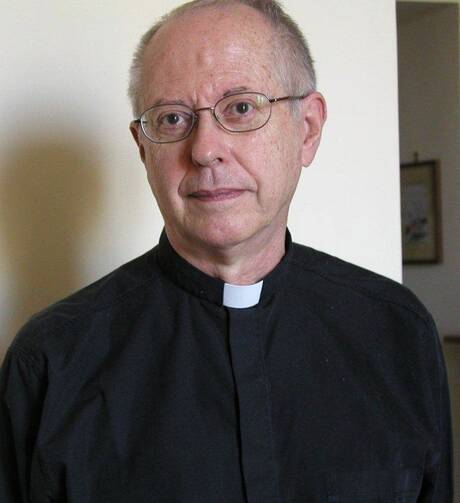

John J. Navone, S.J., is an American Jesuit priest, theologian and writer in residence at Gonzaga University in Spokane, Wash., where he also received an M.A. in philosophy. Father Navone, 85, is also professor emeritus of the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome, where he received his doctorate in theology. The son of Italian immigrants and a dual U.S.-Italian citizen who lived in Italy for 47 years, he grew up in Seattle, where he attended Jesuit schools before entering the Society of Jesus in 1949 after his freshman year of college at Seattle University.

Pope Francis has praised Father Navone, a prodigious writer and media commentator on church affairs, for teaching him about patience in his book A Theology of Failure, also published in the United States by Wipf & Stock under the title Triumph Through Failure: A Theology of the Cross. In his book-length interview with Sergio Rubin and Francesca Ambrogetti, published in English as Pope Francis: His Life in His Own Words, Francis says the following about Father Navone’s book:

Patience is a theme that I have pondered over the years after having read the book of John Navone, an Italian-American author, with the striking title, A Theology of Failure, in which he explains how Jesus lived patiently. In the experience of limits, patience is forged in dialogue with human limits and limitations. There are times when our lives do not call so much for our ‘doing’ as for our ‘enduring,’ for bearing up (from the Greek hupomone) with our own limitations and those of others. Being patient, he explains, means accepting the fact that it takes time to mature and develop. Living with patience allows for time to integrate and shape our lives.

On May 16, I interviewed Father Navone by email about his work on failure and Pope Francis.

Pope Francis cites you as a theological influence and says your book on the “theology of failure” taught him about patience through the example of Jesus. What does patience mean to you and what are some things we learn about the patience of Jesus in the Gospels?

Because all human beings are limited, our love must be a patient love. In fact, patience is the first quality of Christian love Paul affirms because it is foundational (1 Cor 13:4). Patient love is not passive; rather, it is affirming, hopeful and supportive, like that of loving parents with their toddlers and that of teachers with their students. Patience is the sign of true love because it loves others as the finite, limited persons they truly are.

The failure to patiently affirm and support others is the failure to love as Jesus loved and taught us to love. When he taught us the Lord’s Prayer, the only aspect of human relations he mentions is that of our needing to forgive finite, limited others as we, too, have been forgiven. Underscoring our need for patient love, a friend commented to me about a neighbor getting a divorce: “There is no marriage so perfect that if one of the spouses were to seek a motive for divorce they would not be unable to find it.” That same truth applies even to the best of friendships. Jesus was patient with his family, friends, disciples and religious and civil authorities who failed to understand him. Their failure to understand him did not terminate his life-long and loving commitment to enlighten and transform their lives with the good news of his heavenly Father for all humankind.

What does the phrase “theology of failure” mean to you?

The seminal idea for my theology of failure originated with my 1962 ordination retreat at Regis College, in Toronto, given by Roderick A. MacKenzie, S.J. Never before had I ever heard such a heartrending reflection on Jesus’ experience of heartbreaking human failure as when he prepared us for our meditation on the passion and death of Jesus. MacKenzie, a mystic with the gift of tears flowing quietly down his cheek from the beginning to the end of every Mass he celebrated, spoke of the pain of Jesus’ failure as he himself experienced. I can still hear his poignant affirmation:

Jesus was not play-acting when he spoke to his people and religious leaders; he loved them passionately with all his heart! And when he was dying on Calvary, he did not have a consolation of a success story for his lifelong mission; rather, he died with the broken heart of a total human failure!

My theology of failure grew out of the mystical insights of MacKenzie’s ordination retreat into the passion and death of Jesus. Humanly speaking, Jesus had miserably failed to convert his beloved people. He died a total reject. It is only in the light of Christian faith in his resurrection that what failed by human standards succeeded before God. The Risen Christ is the answer of God to human failure. It is the hope, joy and consolation for the billions of little “nobodies” whom the successful and powerful of this world deem to be total failures, that God’s standards of success and failure are not ours.

What counts before God transcends anything that the godless are capable of imagining. The wisdom of God is folly to the godless; the wisdom of the godless is folly to the godly. The mass media evidence the difference in their absorption with wealthy, powerful “somebodies.”

How did failure operate in the life of Jesus and how did he respond to it?

Jesus responded to the problem of failure with a loving patience. Only in the light of his resurrection, would his mother, family, friends and disciples ever truly and fully know what he was all about. His patient love is something like that of teachers who, the first day of class, begin with the patient hope that at the end of the course the students will have learned what the course was all about.

You write that the Father delivers Jesus from failure through the cross. How is dying like a criminal a deliverance from failure for Jesus?

Dying like a criminal is no deliverance for Jesus; rather, his Father’s love is the power that affirms his true meaning and goodness in raising him from the dead. Dying like a criminal represents the Johannine world’s verdict on the meaning and value of Jesus; whereas, the resurrection represents the heavenly Father’s verdict on the meaning and value of Jesus for all humankind.

In John’s Gospel, there is a cosmic conflict between the Prince of Darkness, engineering the condemnation and execution of Jesus, and the Light of the World. The resurrection reverses the verdict of the Prince of Darkness, affirming the verdict of eternal life and love in the life and mission of the crucified and risen one.

Who is Jesus Christ to you?

I came to know and love Jesus as the dearest friend of the persons who were dearest to me. As a child, I came to know Jesus as the dear friend of my parents and maternal grandmother in our intergenerational family. Jesus was a member of our family; we had icons, statues and crosses reminding us of him in nearly all our rooms. We were happy and grateful that he loved and cared for us.

From a theological perspective, my Jesus is the befriending Son of the Father who shares with me the Spirit of their eternal love, reminding me to remember our Father in a ceaseless prayer of gratitude for being the loving origin, ground and destiny of my existence as a “together-with-all-others” under the sovereignty of God’s love. Jesus is the incarnate Word in which our heavenly Father expresses the meaning, value and beauty of all existence. Jesus is happiness itself, incarnate, revealing and communicating happiness itself—the “joy to the world” the angels heralded at his birth.

Jesus is the joy, ultimate meaning and goodness of my life. As a true friend, Jesus knows me and still loves me. In Jesus, I see our Father and enjoy the Spirit of their reciprocity

Who has been the biggest influence on your theology?

When a Jesuit theologian friend proposed his idea for a symposium on the greatest influence on our theology, he assumed that I’d choose Bernard Lonergan. He was somewhat disenchanted when I told him that the greatest influence on my theology came from my parents and maternal grandmother. My reply was in line with that of a prestigious Irish Jesuit friend and theologian who told me that he hoped that his faith was no different from his grandfather’s.

What are some challenges for Catholic theology today?

There are many with an extraordinary facility in god-talk who come across as quite godless. The French film “Ricidule” makes this point with a marvelous brilliance. Jesus frequently made this point in his frequent controversies with the so-called religious “authorities” of his time. The tragedy of self-deception is shockingly clear when he tells “religious” people boasting of having performed exorcisms and healings in his name that they were never his friends.

How do you pray?

Heavenly Father, Son and Spirit, In your light we truly see; In your love we truly love; In your freedom we are truly free; In your peace we are truly at peace; In your joy we are truly joyful; In your wisdom we are truly wise; In your goodness we are truly good; In your life we are truly alive; in your beauty we are truly beautiful; in your happiness we are truly happy. In you alone we live and move and have our being. In you alone we have the hope of unending joy.

Heavenly Father, I thank you for the breath of your life, the wisdom of your Word and the love of your Spirit. I thank you for the meaning of your Word and the joy of your Spirit. I thank you for calling me into existence, holding me in existence and fulfilling my existence. I thank you for the joy of sharing your life, and for revealing the Way, the Truth and the Life of your existence. I thank you for being Our Father, Brother and Spirit. I thank you, Heavenly Father, for the life of your Son and the joy of your Spirit.

Heavenly Father, without your life, I am lifeless. Without your knowing, I am unknowing and unknowable. Without your loving, I am unloving and unlovable. Without your joy, I am joyless and unenjoyable.

Where do you find God in your prayer?

All prayer is a question of God’s reminding us to remember him (gratia operans and gratia cooperans). I pray always, as Jesus requests, because God is reminding me in everything that God holds in existence to say “thank you.” The air I breathe, the ground on which I walk, the light enabling me to see, my body, my friends and all others, the buildings, towns, landscapes, animals, moon, stars and mountains are all the concrete, daily, ongoing ways God is reminding me to say “thank you.”

I am not alone, because my cognitive-affective consciousness is the created effect of the uncreated cognitive-affective consciousness that is effecting it, like the divine electricity that holds the light of my coexisting consciousness in existence. Our consciousness enjoys the immediacy of the uncreated cognitive-affective consciousness effecting the here and now. Consequently, our prayer is always a marvelous reciprocity with the eternal light and love of existence itself, the God in whom we live and move and have our very being.

Having observed all of the things occurring in the world recently, if you could say one thing to Pope Francis about the experience of failure in the life of the Catholic Church today, what would it be?

The perennial experience of failure in the life of the church and that of the entire human family should not paralyze us./ Your Holiness with the fear of making responsible decisions for the common good of the people of God and the entire human community. Confidence in the grace and call of God for courageous decision and action will liberate us/ Your Holiness from the paralyzing fear of unpopularity or rejection. The church today, as in every age, faces new challenges calling for your courageous responses which will inevitably fail to please everyone.

What draws people to Jesus Christ?

Pope Francis’ love for my theology of failure might well distract readers from my theology and spirituality of beauty. Gesa Elsbeth Thiessen’s Theological Aesthetics lists my contribution to this field among the hundred chief contributors from the time of Justin Martyr. Edward Farley, of Vanderbilt University, in his Faith and Beauty: A Theological Aesthetic cites my work among the foremost 20th-century Catholic theologies of beauty, together with Hans Urs von Balthasar, Patrick Sherry, Richard Viladesau and Paul Evdokimov.

I share Dostoyevsky’s conviction that “Beauty will save the world.” Aquinas affirms that God created the world to make it beautiful by reflecting God’s own beauty. Out of love for the beauty of God’s own true goodness, God gives existence to everything, and moves and conserves everything, intending all to become beautiful within the fullness of God’s own true beauty. This implies that God intends creation to be delightful; for the beautiful is delightful. Happiness itself (ipsa felicitas), Aquinas tells us, has created us for happiness itself.

Clement of Alexandra employs Orpheus, the singer and poet of Greek mythology. Who could tame the wild beasts with the beauty of his music, as a symbol of Christ who draws to himself by the beauty of his divine word of truth (Protr. l, 1-19). The self-giving love of Christians attracts us to Christ.

Any final thoughts?

When John’s Gospel affirms that Jesus is “the good shepherd” (Jn 10:11), the Greek adjective used to qualify shepherd is kalos, the word for “beautiful” and “good” in describing the beauty of Jesus’ laying down his life for love of his sheep and the goodness of that life for them (Jn 10:11). The beauty of the shepherd’s self-giving love explains how Jesus, like God, the shepherd of Israel, leads, draws, attracts, unites and sustains his sheep. The splendor of the good/beautiful shepherd on the cross, giving his life out of love for the world, will draw all persons to himself (Jn 12:32).

The beauty of God’s self-giving love in the crucified and risen Christ saves us by drawing us to itself. This grounds Dostoyevsky’s affirmation. Drawn by the transforming beauty of the shepherd, we leave our nastiness and ugliness behind. John’s shepherd metaphor contributes to our understanding the transforming impact of God’s beauty in human life.

Sean Salai, S.J., is a contributing writer at America.

Thank you for reading. You will find the book "Toward a Theology of Beauty" by John Navone SJ here at Amazon.